The success of American Pharaoh in this year’s Triple Crown recalled some lessons I learned years ago from the artists found around the paddocks at Churchill Downs, Saratoga, and Keeneland. Lessons that proved useful to me later in a wider range of subject matter.

Painting horses and riders, hunters and field dogs––in their environment––is a genre known as “Sporting Art” (as opposed to “Sports Art” which depicts human competition, primarily: football, tennis, NASCAR, NBA, etc). All art genres have fuzzy edges, and so do these two; my point being, due to its subject matter they present the artists with specific problems to solve: how to animate the living––and moving––subject.

First a little history:

Before the advent of split-second photography, even the best efforts of the finest artists fell short when it came to rapid motion; errors made by DaVinci were still being made centuries later by Manet. A speeding animal moved too fast for the human eye to deconstruct. Invariably, a horse at gallop was depicted like a hobby horse: legs flying off in pairs––fore and aft. (Just so we are clear: that’s not how it works).

Enter Eadweard Muybridge, hired by California Governor Leland Stanford in 1872 to settle this question through methodical photographic evidence: “Does a horse, while moving at a trot, ever have all four legs suspended in the air?

To relieve your suspense––it does and they do

Remington did not rely on a particular Muybridge image so much as apply the knowledge he gained from the motion studies. Remington used a Kodak––extensively, for about one year––before coming back to the sketchpad. He later wrote: “The artist must know more than the camera…” He routinely altered anatomy and distorted action to attain a realistic effect of movement. For example, in Remington’s Stampede (above) not only is the action of the horse exaggerated, its rump curls unnaturally low, the rider leans forward (in perfect balance) with his horse, the brim of his hat is snapped back, the fleet gait of the horse juxtaposed against the lumbering, more static, action of the herd. The rain at their backs seems to hurry all the figures forward into the night.

Remington achieves what we all strive for: veracity without an overreliance on minutia. Something I should strive for in my writing.

The “secret” I picked up from the artists working the racetracks was to observe repeated motion––to let that be my starting point. There are patterns and rhythms in the most vigorous motion––“method in the madness” if you will.

The point is: observing the thing repeatedly––like watching waves come onto shore––until you understand it completely and can now begin to appreciate the nuances of action that make one horse/animal/dancer/wave different from another.Sir Alfred Munnings’ many “Racing Start” paintings (there are dozens) are wonderful examples. In one of the most famous of these Munnings employs the device of a clever title, one that invites the viewer to stand beside the artist as the horses are held in check a moment longer.

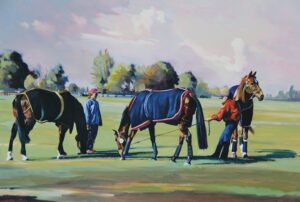

Below, is one of my efforts that (I think) illustrates motion does not need to be flagrant. Motion is implied by the tension on the lead shank of the middle horse––who is determined to reach some particulate of desire. The horse on the right is attracted by something “off-stage;” the light breeze of an English Spring indicated by the position of the tails and the sky, the handling of the background trees.

Dance is a great opportunity to develop this skill. It is repetitious and (if you learn the choreography) it is predictable. I was led to an appreciation of dance, as subject matter, by a friend of mine––a horsewoman.

Dance is a great opportunity to develop this skill. It is repetitious and (if you learn the choreography) it is predictable. I was led to an appreciation of dance, as subject matter, by a friend of mine––a horsewoman.Purely as a favor (as I thought of it), I agreed to go down to our local dance studio and watch her teenage daughter prepare for that year’s Nutcracker.

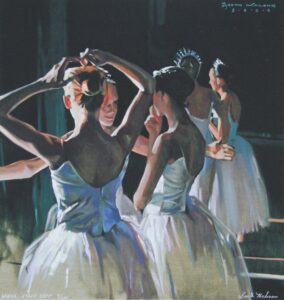

I’ve been painting dance figures ever since. I immediately saw what Degas (who also painted horse racing) had seen…the appealing similarity in movement between horses and young dancers: speed, strength, focus.

I’ve been painting dance figures ever since. I immediately saw what Degas (who also painted horse racing) had seen…the appealing similarity in movement between horses and young dancers: speed, strength, focus.

In painting dancers the challenge comes in not only depicting movement, but that movement occurring under challenging lighting. As with horses, you can’t just aim a camera, take a few (hundred) shots, and head back to your studio. You have to understand what you see to depict it accurately.

In painting dancers the challenge comes in not only depicting movement, but that movement occurring under challenging lighting. As with horses, you can’t just aim a camera, take a few (hundred) shots, and head back to your studio. You have to understand what you see to depict it accurately.In the gloom of the wings––offstage––the dancers bend and stretch, twirl and practice, gossip; they fix their hair, wait for their cue––and do a thousand other things––many interesting moments that are gone in the blink of an eye. But my mind remembers what my camera never seems to, and the fun is to try and recreate that moment on my easel.

Today cameras fit in our shirt pockets and take better photographs than Muybridge ever dreamed. But when it comes to painting motion it still pays to “know more than the camera.”

Click here to visit Booth Malone’s Personal Website.

www.boothmalone.com

Marsha Savage says

Enjoyed this conversation with us! Very good practical advice. I have stood in the ocean for hours and watched the water and the waves and I know I paint good waves because of this. So, why wouldn’t it apply to all other aspects of things in motion! I believe this is a rather “Duh” moment for me, and why didn’t I think of this in relation to other things! Thank you for pointing this out.

K Meadows says

Really? Your painting showing ‘motion’? I think not. It appears stiff and more like a cardboard cutout as does your dancer painting, which by the way is an oversaturated subject matter. You should leave the dancer paintings to someone who knows how to do them right like Dan McCaw, and horse paintings to the master Munnings who will never be matched.