Attending my high school class’s fiftieth reunion this past June has me in a reflective mood. Home, back then, was South Florida, and I had not been ‘home’ for many years.

It was a good school, Coral Gables High. A large and diverse student body; integration came in ’65––our class was the first to go all three years together––but South Florida was already a melting pot and that was no big deal, at least at our school.

A moment ago I was listening to a song on Pandora; one I often heard played years ago: Thanksgiving, by pianist George Winston. He made the recording in the late seventies I think, and then went on to sell literally millions of albums. Triple Platinum. To help out I bought several; still have them, awaiting vinyl’s inevitable return.

George graduated a year ahead of me at old Gables, captain of the varsity in basketball and baseball his senior year. So who suspected he also played piano? Not me, certainly. In my own class, a skinny kid, Winston Scott––in my mind I see him clearly, playing trumpet in the middle of our school band’s brass section––became an astronaut. What the––! Another boy I knew chalked a cartoon on the blackboard each week of football season, lampooning the opponents in our next game. Between classes everyone would peek into that classroom to see what he had drawn. Frank wound up in Hollywood and was Artistic Director for Shark Tales and Sinbad. Okay, I should have seen that one coming––didn’t––I was not even aware my school had an art club. I could draw––could even cartoon––but so what? Couldn’t lots of people? No? Really? Well, never mind––no one makes any money at that anyway.

My younger self put so much effort into being unremarkable.

My point (and I almost always have one): like many young people, I had talents or, at least I had a talent. What I lacked was the imagination to develop it, the confidence to follow it. George, Winston and Frank saw doors and went through them. All I saw was a room. Rooms are comfortable places. Safe.

Imagination, creativity––drive; these are all ‘muscles’ inside us that have to be exercised and developed to reach our potential, just as an athlete builds up and trains his/her body. In 1968 my imagination was the proverbial ‘ninety-pound weakling,’ and I was not into exercise.

I did not take my first art class until my junior year in college. I immediately switched curriculums. My talent was evident––but I could not see the career steps to follow, and no one was offering advice. Still in my ‘room.’ It was not until I was out of college that my imagination finally kicked in, and I found my first door. I can even identify the moment: seeing John Singer Sargent for the first time. “I have to learn how to do that!” My job at that time had me on the road, so I visited museums regularly––the L.A. County Museum, the Gilcrease, the Amon Carter––and examined the early work of famous artists. I noted some of it was not so good––which was actually encouraging: “Why, I can do better than that!” I began to read and to learn––calisthenics if you will––something just as important as ‘exercise’.

Long story, short: I did not pursue art professionally until I was thirty-four. Just one year later I got very lucky: horses.

I am from among the ‘bootless and unhorsed’––I am not, have never been (and never will be) a horseman––yet I stumbled through a wonderful door into the field of painting horses: “We make brown look good.” Ahem.

By happenstance I fell in with horse people who took the time with me to explain the subtleties of their particular sport (which are numerous) or the characteristics of a particular breed (even more numerous) When I was shown paintings by Munnings, I (again) said: “I have to do that!”

Now I say to others: “You have to do that.” Don’t suppress your talent. Find the doors. Every question of subject matter, composition, technique, is a room you are placed in. It is your job to find the exit doors. They may lead only to another room. But there you will find fellow travelers: ask lots of questions, that you may be prepared to leave many answers.

It is the way it is done.

I would not change a thing, if I could turn back the clock. (Once I became an artist that is––who wouldn’t tinker with their high school years?) Painting horses and equestrian venues exercise and combine all my (current) artistic desires. Horses are the most varied, versatile, nuanced, and aesthetic animals on the planet, the most difficult to ‘bring off’, presenting a never-ending challenge for figurative painters, or for painting landscape, historical events, materials, textures, equipment, lighting, action, motion.

Not everyone thinks of ‘horse painters’ that way––I know that.

It is just the room they are in.

The 2017 National OPA Convention in Cincinnati

Why Every OPA Artist Should Attend This Event

If I may borrow from actor George Takei: “Oh My!”

I never expected to see John Michel Carter, Kathryn Beligratis, Bill Whitaker, or Suzie Baker together in a conga line – or myself for that matter – but that was what the closing party for the OPA’s 26th Annual National show was like.

The venue for the party, Cincinnati’s American Sign Museum, was just the place for painters, patrons, venders and friends to kick up their heels. The unusual surroundings (iconic neon signs and memorabilia from the fifties and sixties), capped an unusually relaxing and comfortable four days along the banks of the Ohio.

With the weather and temperature cooperating, the river and the city parks were within walking distance – as were the fine dining and Graeter's Ice Cream. Friday, Saturday and Sunday were packed with informative demos and presentations. More things to do and see than any one person could take in.

The reason most frequently given for not coming to an OPA National Juried Exhibition is: “I didn’t get in.” With all respect, if you are waiting for that you are missing the point of a conference. The annual show provides every OPA member the opportunity to see and learn, to meet and to exchange ideas with other artists. And by missing the National you’re just missing a lot of fun.

A painting demonstration by William Whitaker OPAM is always as entertaining as informative, and he was followed on Friday by a portrait demo by Johanna Harmon and still later, a presentation by David Mueller: “Sophisticated Fundamentals.” Many who attended this talk came away with the feeling they had just gotten their money’s worth for coming to Cincinnati. I could go on, and maybe I should – but whenever I hear that phrase spoken, I’m already tuning out.

I will just make a plug for next year’s conference: Steamboat Springs, Colorado – a place as beautiful in the summer as it is the rest of the year.

I’ve been on both sides of the equation myself, but can’t say ‘in-or-out’ has ever deterred my attending a show. If time, distance, and budget cooperate, the opportunity to see, meet, hear and learn from your contemporaries cannot be missed.

At every conference I’ve attended, information is exchanged constantly and freely: technical, material, professional. It is there for the asking.

Quite literally, going to OPA events has made me a better artist.

Okay. That’s the business end.

The real story was this: Cincinnati was a great place to go, just to have fun with your ‘peeps.’

Cincinnati may have been the best yet.

Seeing the paintings accepted into the annual OPA online or in the catalog, is a poor substitute for the real thing.

Opening Weekend Events: May 30 – June 3, 2018

“KWAK AND LUG”

The first artist (let’s call him ‘Kwak’) faced the first dilemma: “How do I price my work?”

The first artist (let’s call him ‘Kwak’) faced the first dilemma: “How do I price my work?”

Kwak was a natty little Neanderthal, not much good at physical labor (and before anyone shakes a spear at us, we recognize those researchers who attribute the bulk of his work to his unsung partner ‘Wampat’), but…be that as it may: Kwak had just finished a fine head study of the Old Chief’s mastodon and was at a loss what to charge. Kwak turned to his best friend (who was even less adept at labor––but dreamed of opening a gallery), and asked him:

“So, Lug––be honest: How many seashells can I ask for this?”

Lug (a little miffed at being asked to ‘be honest’––for he was invariably honest) replied: “It’s not what you can ask, Kwak––it’s what you can get. Old Chief doesn’t like to part with his seashells.”

Well, thought Kwak: Tell me something I don’t already know.

Sensing Kwak’s disappointment, Lug said: “What if I go to Old Chief? Would you take ten seashells for it?”

“Well…” Kwak was hesitant.

But Old Chief was to be avoided if at all possible. He was a scary old guy, always asking Kwak when he planned on doing some real work.

Lug sweetened the pot: “Look––if I can get more, I will. I don’t want to leave any seashells on the seashore any more than you. We’ll split whatever I get, down the middle: sixty/forty. How’s that sound?”

“Pretty sweet,” Kwak agreed.

Now Lug was just as afraid of Old Chief as everybody else, but seashells are seashells. He caught Old Chief at an opportune time: just back from the seashore–– and loaded with seashells.Lug pointed out what a fine rendering Kwak had done; his work on the mastodon’s tusk was exquisite: worth ten seashells by itself. He also mentioned the rarity of the piece (for it was, indeed, the first piece of artwork). In Lug’s eyes, that doubled its value. Finally, lowering his voice, Lug said he hated to bring this up–– was very apologetic to Old Chief––but (full disclosure) the young chief in the next valley, Eats-Seashells-For-Breakfast, had expressed an interest in Kwak’s mastodon…

“But that’s my mastodon!” Old Chief shouted and sputtered. He was outraged.

“Yes Sir. You are quite cor-rect. Though, act-u-ally, in this case…er, by, um, tribal custom, Sir––Kwak has the rights to the image…but that is stuff for a future blog, and nothing you need worry about today…”

Old Chief grumbled…

“Eats-Seashells-For-Breakfast wants it, eh?” (Old Chief was Canadian on his mother’s side) “Well, Lug, you are a thief, but I’ll give you thirty seashells for it, and not a single seashell more.”

“Will that be cash or credit, Sir? And…um, sorry––we must remember the sales tax. We can’t forget Big-Chief-On-The-Mountain.”

Lug was very proud of his day’s work. He had done a favor for his best friend and got him some extra seashells to boot. He also had enough shells to open that gallery. He knew just the spot…right on the path to the seashore.

Kwak too was proud of his day’s work. He had gotten Lug to shake some seashells out of Old Chief. No easy thing. His work was now where other Chiefs might see it. True, he had expected ‘sixty/forty’ to be worth more than twelve seashells––he had never been good at math, having skipped school that day––but, whatever, it was two more seashells than he could have gotten on his own.

His wife, on the other hand––for reasons Kwak could not quite follow––was not happy. Not–happy–at–all. She (nee: Wampat Goody-Two-Boots) had never missed a day of school, and was quite sure Miss Google had demonstrated the concept of ‘down the middle.’

Gently, Wampat asked Kwak if he had gotten this agreement with Lug down in writing.

Kwak gave her a blank look and asked: “What’s wr…”

Wampat threw up her hands and stormed out.

Notes: Painting Subjects in Motion

The success of American Pharaoh in this year’s Triple Crown recalled some lessons I learned years ago from the artists found around the paddocks at Churchill Downs, Saratoga, and Keeneland. Lessons that proved useful to me later in a wider range of subject matter.

Painting horses and riders, hunters and field dogs––in their environment––is a genre known as “Sporting Art” (as opposed to “Sports Art” which depicts human competition, primarily: football, tennis, NASCAR, NBA, etc). All art genres have fuzzy edges, and so do these two; my point being, due to its subject matter they present the artists with specific problems to solve: how to animate the living––and moving––subject.

First a little history:

Before the advent of split-second photography, even the best efforts of the finest artists fell short when it came to rapid motion; errors made by DaVinci were still being made centuries later by Manet. A speeding animal moved too fast for the human eye to deconstruct. Invariably, a horse at gallop was depicted like a hobby horse: legs flying off in pairs––fore and aft. (Just so we are clear: that’s not how it works).

Enter Eadweard Muybridge, hired by California Governor Leland Stanford in 1872 to settle this question through methodical photographic evidence: “Does a horse, while moving at a trot, ever have all four legs suspended in the air?

To relieve your suspense––it does and they do

Remington did not rely on a particular Muybridge image so much as apply the knowledge he gained from the motion studies. Remington used a Kodak––extensively, for about one year––before coming back to the sketchpad. He later wrote: “The artist must know more than the camera…” He routinely altered anatomy and distorted action to attain a realistic effect of movement. For example, in Remington’s Stampede (above) not only is the action of the horse exaggerated, its rump curls unnaturally low, the rider leans forward (in perfect balance) with his horse, the brim of his hat is snapped back, the fleet gait of the horse juxtaposed against the lumbering, more static, action of the herd. The rain at their backs seems to hurry all the figures forward into the night.

Remington achieves what we all strive for: veracity without an overreliance on minutia. Something I should strive for in my writing.

The “secret” I picked up from the artists working the racetracks was to observe repeated motion––to let that be my starting point. There are patterns and rhythms in the most vigorous motion––“method in the madness” if you will.

The point is: observing the thing repeatedly––like watching waves come onto shore––until you understand it completely and can now begin to appreciate the nuances of action that make one horse/animal/dancer/wave different from another.Sir Alfred Munnings’ many “Racing Start” paintings (there are dozens) are wonderful examples. In one of the most famous of these Munnings employs the device of a clever title, one that invites the viewer to stand beside the artist as the horses are held in check a moment longer.

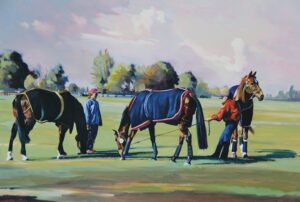

Below, is one of my efforts that (I think) illustrates motion does not need to be flagrant. Motion is implied by the tension on the lead shank of the middle horse––who is determined to reach some particulate of desire. The horse on the right is attracted by something “off-stage;” the light breeze of an English Spring indicated by the position of the tails and the sky, the handling of the background trees.

Dance is a great opportunity to develop this skill. It is repetitious and (if you learn the choreography) it is predictable. I was led to an appreciation of dance, as subject matter, by a friend of mine––a horsewoman.

Dance is a great opportunity to develop this skill. It is repetitious and (if you learn the choreography) it is predictable. I was led to an appreciation of dance, as subject matter, by a friend of mine––a horsewoman.Purely as a favor (as I thought of it), I agreed to go down to our local dance studio and watch her teenage daughter prepare for that year’s Nutcracker.

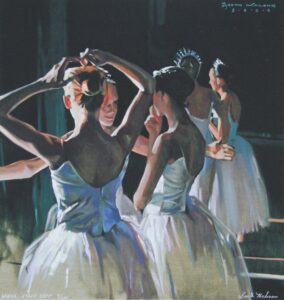

I’ve been painting dance figures ever since. I immediately saw what Degas (who also painted horse racing) had seen…the appealing similarity in movement between horses and young dancers: speed, strength, focus.

I’ve been painting dance figures ever since. I immediately saw what Degas (who also painted horse racing) had seen…the appealing similarity in movement between horses and young dancers: speed, strength, focus.

In painting dancers the challenge comes in not only depicting movement, but that movement occurring under challenging lighting. As with horses, you can’t just aim a camera, take a few (hundred) shots, and head back to your studio. You have to understand what you see to depict it accurately.

In painting dancers the challenge comes in not only depicting movement, but that movement occurring under challenging lighting. As with horses, you can’t just aim a camera, take a few (hundred) shots, and head back to your studio. You have to understand what you see to depict it accurately.In the gloom of the wings––offstage––the dancers bend and stretch, twirl and practice, gossip; they fix their hair, wait for their cue––and do a thousand other things––many interesting moments that are gone in the blink of an eye. But my mind remembers what my camera never seems to, and the fun is to try and recreate that moment on my easel.

Today cameras fit in our shirt pockets and take better photographs than Muybridge ever dreamed. But when it comes to painting motion it still pays to “know more than the camera.”

Click here to visit Booth Malone’s Personal Website.

www.boothmalone.com