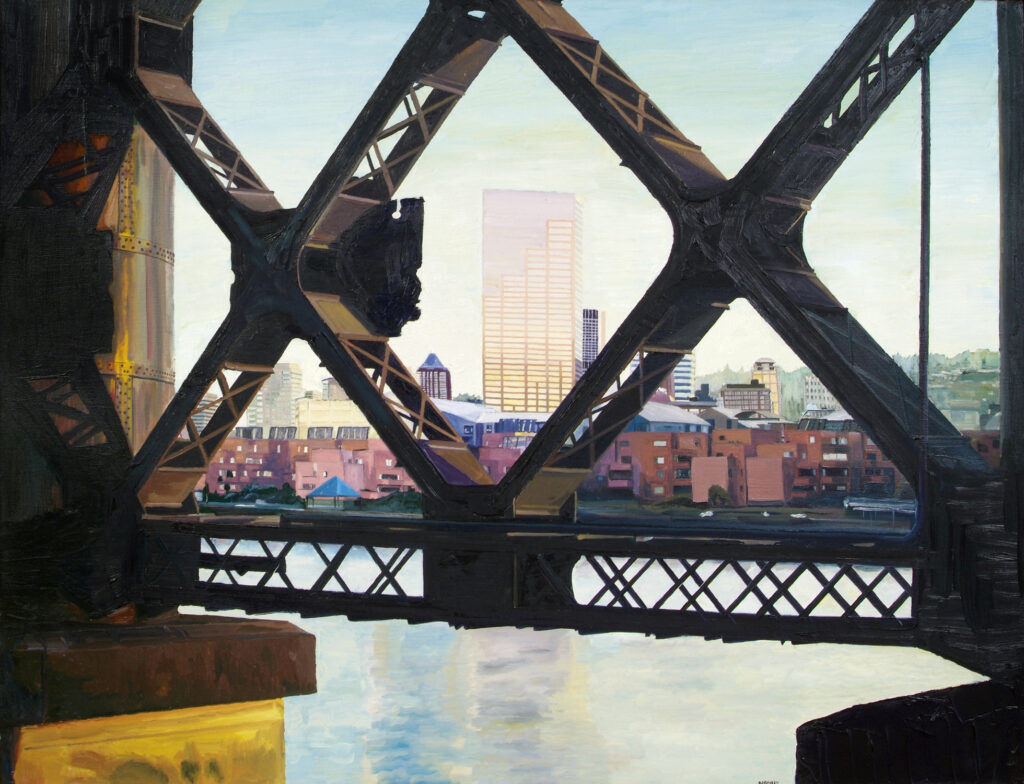

30″ x 40″ – Oil

“Do a large piece of smokestacks, Chris!” said David Passalacqua, one of my favorite teachers during my senior year at Parson’s School of Design.

What? I just looked at him, feeling a bit awkward. I wasn’t sure why he said that. I looked at my work in progress. I had a decent, albeit slightly boring, illustration going. I wasn’t ready to give up on it.

David was an excellent and very extroverted teacher. His friendly eyes had an uncanny ability to bore a hole into your soul by looking at you with the surety he had for his craft, and then yank the guts of your creative instincts to the fore.

That is what happened to me when I looked at him.

He was brutally honest with me—as he was known to be with students—through just a mischievous smile and an electric energy spilling from his deep knowledge of illustrative art. He made it his mission to challenge students to higher levels.

“OK,” I said to him calmly, while energy surged through my body. Something central changed that day for me. My journey as a painter became a passionate adventure—a mission to capture the unimaginable. I completed three paintings of the Con Edison Power Plant on 14th Street, not too far from Parson’s, and received an A. That was 40 years ago.

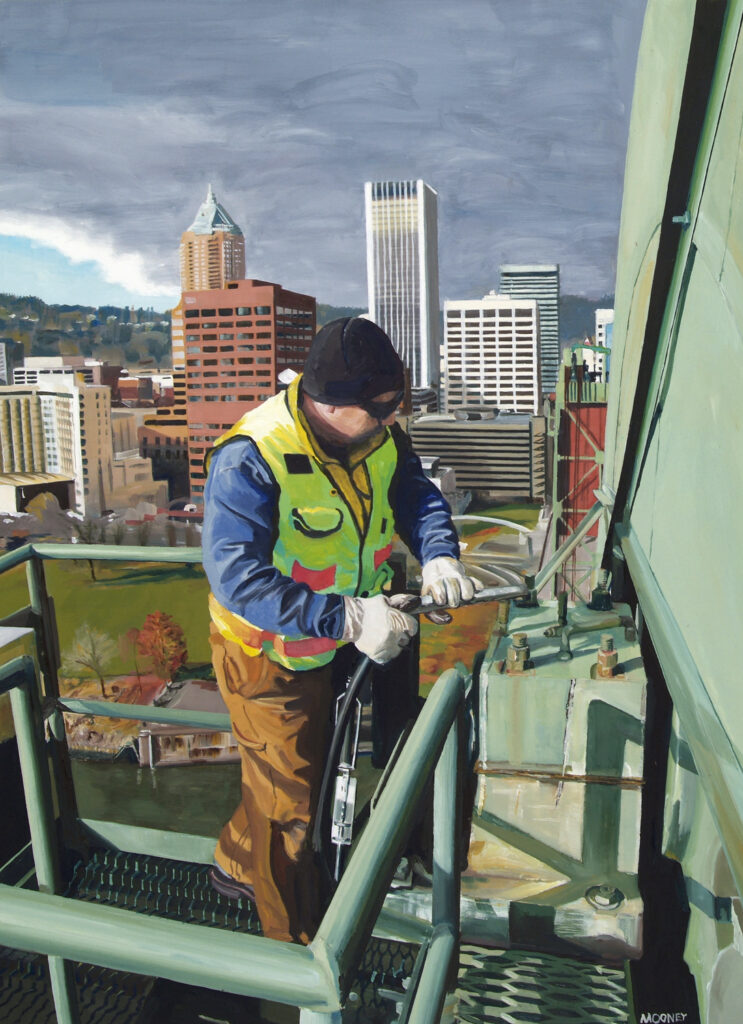

48″ x 36″ – Oil on Canvas

I was born and raised in New York State, surrounded by an artistic family and a richly influential environment. My mother, during her first trimester of pregnancy with me, contracted measles. As a result, I was born without hearing. I neither heard nor spoke until I was about four years old when I started wearing hearing aids. Today, I wear corrective devices and speak well.

When you’re deprived of one sense from an early age, the other senses compensate by growing stronger. In my case, it was my eyes. They taught me everything I knew about the world I had been born into. My sight continues to be my dominant sense, the only truly reliable way I have to perceive my world, and the sense that informs my work. I work very hard in my paintings to convey the strength and the beauty that I see.

Living in Portland, Oregon, for most of my adult years, I have established a niche in the art community as a painter of contemporary realism. A significant body of my work showcases Oregon’s diverse architectural styles, especially its bridges. The rivers and twelve bridges of Portland are crucial to the city’s character and function, and they provide a great source of inspiration for me.

36″ x 48″ – Oil on Canvas

These bridges compel us to stop and look, be still in the moment, and breathe in the ingenuity of a grand structure. Hiking around the city, I carry my camera for photo references I use for inspiration. I step off the sidewalks to get different perspectives of the city and its bridges with the intention of adding a new dimension to my work.

I am fascinated by the complex steel girders and geometric shapes that underpin the majesty of the bridges. Building dramatic perspectives in my paintings, I illustrate the steel girders in compositional perspective, and capture the transition between the landscape and the cityscape. I strive to deliver unusual points of view, and render exciting realistic and abstract portrayals.

36″ x 48″ – Oil on Canvas

To me, building and maintaining bridges represents a fantastic human achievement. Having the opportunity to be on a bridge during construction or repair also puts me in close contact with the crews—the working heroes—who maintain it.

On one occasion, the Multnomah County Bridge Maintenance crew of Portland invited me to go with them to the top of Hawthorne Bridge and watch them do the greasing of the bridge’s bearings, and the maintenance of the operating mechanisms. I felt privileged to be able to document the maintenance of a bridge and then create art illustrating these American workers, who often go unrecognized and are forgotten.

24″ x 18″ – Oil on Hot Press Arches Paper

I have a mission to recognize the people who are an essential part of the creation and maintenance of these important structures. This mission led to a grant I received from the Regional Arts & Culture Council for a project called Tributes: Portraits of Working Heroes of the Tilikum Crossing. I created a visual record of building the Tilikum Crossing for a Portland light rail bridge over the Willamette River. I painted portraits of the designers, engineers, builders, and contractors who worked on the project and featured them in their working environment.

48″ x 60″ – Oil on Canvas

Bridges frame our landscape. They aid commerce, and create vital connections between communities. People cross bridges every day, yet few realize how little we celebrate the modern marvels of their engineering and of the workers who maintain them. My hope is to inspire others to feel more connected to our collective human achievements through viewing these paintings.

It is also necessary to find happiness in what you do. I derive great personal joy knowing that Charles Sheeler, Edward Hopper and Charles Demuth were painting just these kinds of subjects.

60″ x 48″ – Oil on Canvas

While striving to create the unimaginable with my artwork, I still face the reality of competitive judgment and juried shows. I want to be a part of these things, of course, but they conjure feelings of vulnerability and fear of the unknown. I know I have to be courageous to put my soul on canvas to discover if my work could inspire and move other people in some way. I want people to see beyond what is before them in order to feel what I do—a beauty and a great spaciousness that holds the mysterious connection living within us, among each other, within our landscapes, and inside our communities.

22″ x 28″ – Oil on Canvas