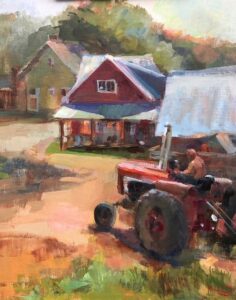

7” x 8” – Oil

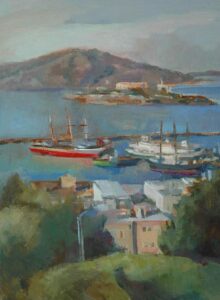

Now that I refuse to board an airplane and fly across country, I miss my family and friends. My plein air workshop at the Landgrove Inn in beautiful Vermont has been canceled, and my trips to NYC, specifically the MET, have been on hold. I live near San Francisco with my husband and son. This has been a time of painting locally.

My studio was relocated from Oakland to my backyard. I have used this time for reflection and growth, integrating skills that I have spent a lifetime accumulating. I have taken some online courses and attended virtual conventions: DrawingAmerica and Realism Live to name two. All the while, I have tried to find a remote teaching job at the local private schools. I know one thing about this pandemic: you cannot run around and hang out with friends. Workshops and onsite teaching opportunities have all been cancelled. This is a time of resilience, a time to consider all the diversity training available, and a time to be thankful for what is in the moment.

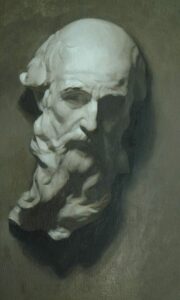

11” x 14” – Oil

During the Realism Live Convention, Patricia Watwood, Jennifer Balkan, and Alia El-Bermani discussed gender bias and the imposter syndrome which set off a bell for me. I could write a whole article on that syndrome, but instead, with this Covid “pause,” I discovered new coping strategies which otherwise would have just blown right by me. I have always been part of an art community. However, during the pandemic, it is no longer available. So, spiritual self-reinforcement has become necessary.

Out in my backyard, to get beyond the blank canvas, I start with a series of questions:

Why is that beautiful?

What are the shapes?

How can I frame that?

How many compositions/thumbnails can I make with that idea?

Which idea is best?

How varied are my value shapes and are they interesting?

What are the main colors and values, and does that affect my focal point?

(One thing I truly love and notice is how colors react next to each other…)

How should I approach my color studies?

Cast drawing and painting has humbled me to the core, and I can say I was not the best at it. I understand how difficult it is to set up a hierarchy of values and edges. This ultimately is the greatest challenge in any painting, and the concept should be considered early.

12” x 9” – Oil

I find it interesting that some people have confidence right from the start and eventually catch up with their skill sets, while others are always thinking they are not good enough. My own self-doubt arises when I don’t sell my work and there is a very slow market.

The truth of my training outweighs any imposter syndrome-feeling: Pratt Institute, the Academy of Art in San Francisco and Training at Golden Gate Atelier in Oakland with Andrew Ameral from Florence Academy. But this weird world presents its own tests.

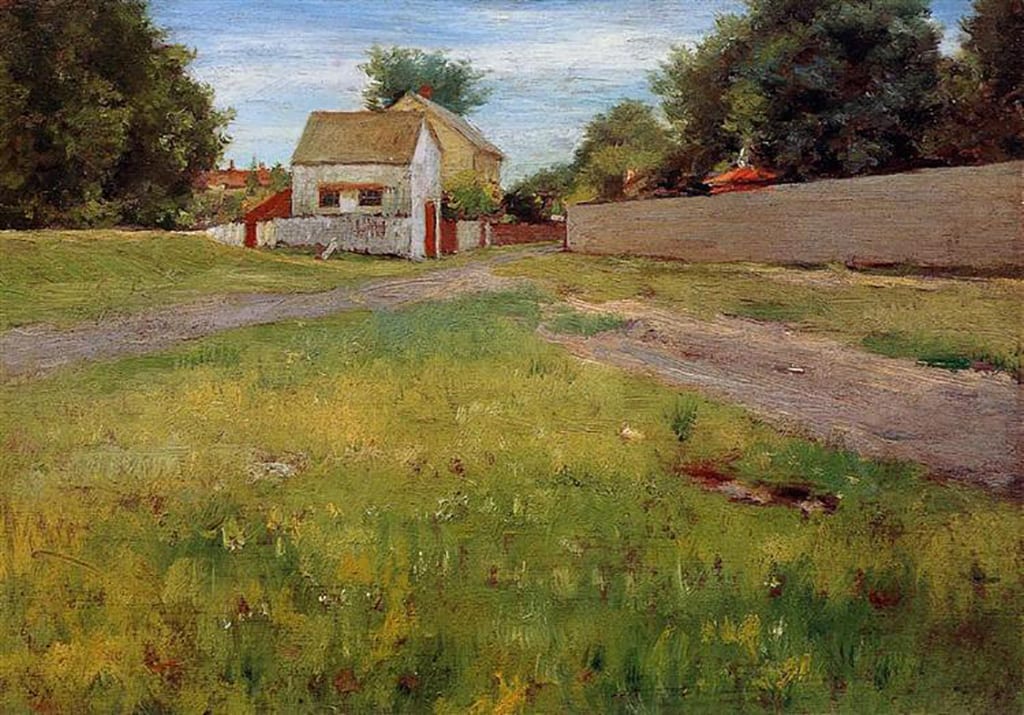

To be an artist requires grit and perseverance. Practicing art is an act of faith. The Covid situation has made it necessary to isolate from many social activities. My creative mission became to find beauty and truth in the ordinary; to “be where I am,” even if that meant a lot of solitude. I am motivated, however, when artists such as William Merritt Chase and Adolf Menzel show me how they made masterpieces by staying local and simple.

William Merritt Chase (1849-1916) found a world to paint in his own backyard. Relentless with his education and drive, he was stylistically flexible with his portraits, landscapes, and still lifes. I appreciated Chase even before the pandemic. His works are carefully composed views of his reality. His paintings of Central Park resonate with me on a very deep level. I have walked through the park, over the land where Chase painted. One idea, still pretty new to the US, is that we are just passing through—that the past, present and future all contain gifted and talented people to capture the same hills, lawns, trees and vistas.

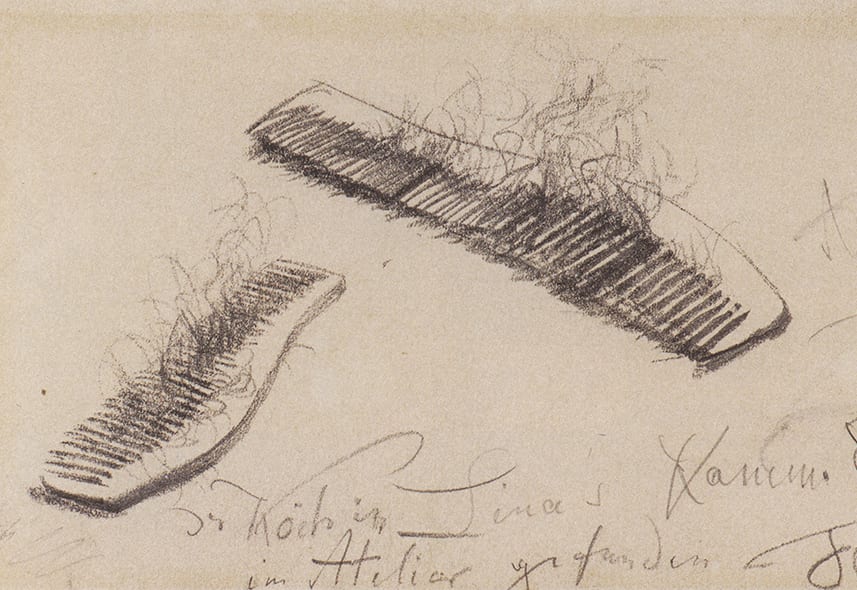

Adolf von Menzel (1815-1905), a German painter and printmaker, resonates with me especially during this time of isolation. To some degree, Menzel was detached from others. He became famous toward the end of his life for historical and patriotic paintings. But for me, his ability to see the beauty in common objects is a great lesson. His drawing of a comb with hair illustrates my point: find something common, a simple object to draw, and make it interesting.

The Japanese culture embraces an idea called Wabi Sabi. The word Wabi describes loneliness, not the negative feeling of isolation from others, but rather a pleasant feeling of being alone in nature, away from society. Sabi means to be old and weathered, but in an elegant, rustic fashion. In our culture, we do not often confront loneliness. Wabi-sabi is also about appreciating simplicity, and seeing the value in small things. This past year has forced me to do so, and being “stuck” in my backyard studio turns out to be a positive: it allows me to observe detail in a new way. I would have missed the delight and creativity in the ordinary. Take a moment to look at what is around you wherever you are. I hope that it stirs and inspires you, just as it did Chase, Menzel—and me.