I consider myself a colorist. That is, I find that color palette inspires the visual message I wish to convey in my painting. Interestingly though, color is subordinate in what I do. As a more-or-less representational painter, color always submits to value. My goal is to make a thing look like a thing. And the way to achieve this is through getting my values on point, and by accurately drawing patterns of shapes in order that the abstract pattern ultimately mimics the likeness of a thing. Color is inconsequential at this stage. It is through attaining an accurate pattern of shapes varying in tone that I create my visual interpretation and representation of what is natural.

Now these values, or patterns of light and dark shapes, take their form in particular mixtures of colors. And it is through achieving an accuracy in these patterns that we can then create the illusion of three-dimensional form on a two-dimensional surface. And as we create this illusion, and make our marks with intention, we eagerly guide our viewers through our painting compositions. Through the particular choices of colors used in the manners that follow, I use color to make my visual statement.

Color is only one of the common elements in a work of art. Elements are stylistic features through which an artist conveys her visual expression. (Other elements are line, shape, form, space, texture and value.) An artist might adhere to several of these elements in a work, but choose to emphasize one in particular and use it to make the visual statement.

There are various approaches to using color in painting. It can be used as light; as tone; as pattern; as form; as symbol; as movement; as harmony; as contrast and as mood.

As artists, we choose color that evokes a particular mood; sometimes the degree of chromatic intensity determines a state of emotion. Relationships among the intense and the diluted can determine harmony. Color harmony refers to “the property that certain aesthetically pleasing color combinations have.” These combinations include both the opposing and the compatible on the color wheel, the sum of which creates an agreeable accordance, like a set of satisfying musical chords in harmony. But the way humans respond both emotionally and perceptively to color and mood is not objective; it may be subject to age, gender, and personal preference for example. Additionally, cultural and social-based differences affect how we learn about color.

Describing form by varying color and value is one way to create the illusion of three-dimensionality on a flat surface. Those of us with full color vision get to discern the subtleties in color variation. Artists can shift hue or family of color according to temperature as well. In the art world, painters have historically marveled at the optical illusions that artists have learned to impress upon their viewers. One such illusion, employed by the Impressionists, involves adjusting color in alternating color temperatures while increasing or decreasing value. This method makes use of applying color as contrast. This trick helps to create the illusion of three-dimensionality or three-dimensional form. Furthermore, one might choose to increase or decrease saturation in these alternating swaths of color and value mixture. Another significant aspect of this technique is that it implies broken color or optical mixing: instead of blending values and paint mixes together, the artist lays down discrete strokes side by side and the optic nerve in the brain perceptually mixes the color.

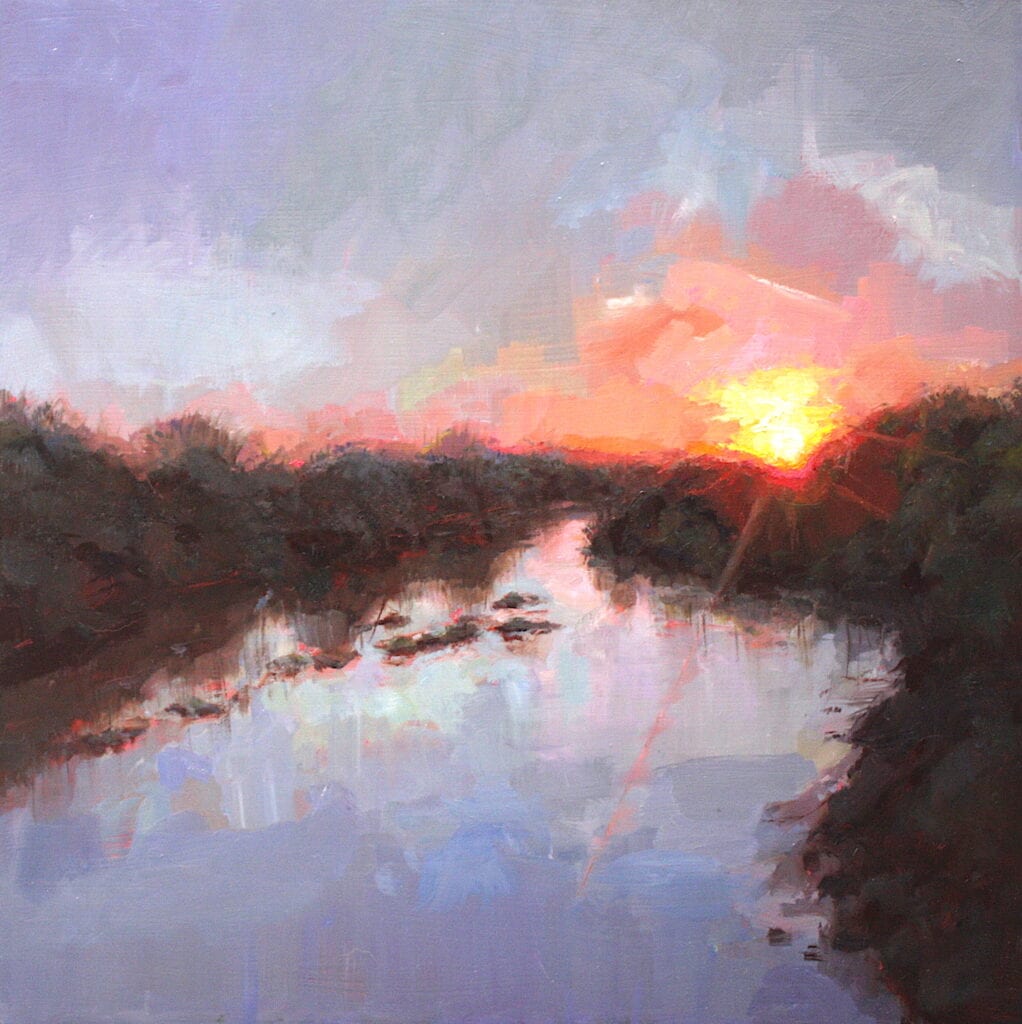

Contrasting color can be a way to draw the viewer into parts of the painting. Manipulating the saturation level of a color in relation to its surrounding colors helps draw the viewer to a focal point. For instance, raising saturation in one area, in relation to surrounding muted colors, will cause the saturated area to stand out or attract attention.

Though the science is questionable on color, my experience with museum work, art appreciation, and my perception of work being done by current artists, reveals certain patterns of color relationship that please. An artist invites a viewer into their work and navigates them through a painting by creating focal points that attract the eye, like key points within a map. These key points can be distinguished through sharp edge work, high contrast, and saturation of color. For me, it is through high contrast or the juxtaposition of disparate values coupled with elevated intensity of chroma where I find resonance in a painting. And here, color can be used as light.

Through navigating form through color, emphasizing and exaggerating light in color, contrasting temperature in color, using color as tone or value, and using color as form and creating color harmony, I make my visual statement through the element of color. I deliberately craft focal points demonstrating these different usages of color. There are often a few focal points or areas to rest on. And it is through the manipulation of color choices that I guide my viewer through a painting. I think of a painting as a geographic map: the eyes of the viewer are the explorer who bounces around from one significant point to the next, taking a road or river to the next stop. The individual points are compelling enough to spend a little time in, but the next one beckons and the traveler moves on to explore the land mass in its entirety.