I’m not a naturally patient person. I tend to want to skip the hard part and get to the results, but learning to make good paintings is a process that takes time. Beginners are often surprised by how difficult drawing and painting actually is. Layers of fluid brush strokes in a fine painting give the impression of easy spontaneity, when in fact, the artist made innumerable, calculated decisions throughout the process.

When I went to art school in the 70s and 80s I was surprised by the lack of instruction in my studio classes. We had critiques and discussions about design concepts, but technical training was curiously absent. This approach was evidently based on the idea that classical instruction would stifle or hinder creative expression.

Compelled to undertake this approach, I abandoned what I’d learned from an excellent high school art teacher, and began slathering pigments onto large canvases, using sweeping gestures and full chroma color. I imagined that somehow the innate qualities within me would find their way onto the canvas. This was great fun at first. The freedom to move the paint around spontaneously was invigorating. It was like being a kid again. Eventually, the newness wore off, and I became bored with my limitations.

After college I got a job at a gallery that exhibited some extraordinary representational paintings – the kind of paintings that had inspired me to become an artist in the first place. Next to these, my work seemed ridiculous. I held to the notion of my professors, that if I just kept painting, my work would naturally develop on its own. This proved to be untrue. I was stuck, lacking the skills to do what I envisioned in my mind, and the resources to obtain those skills. The university had my money and I had very little to show for my investment.

A move and change in circumstances led me to lay aside my brushes for a number of years. When I finally resumed painting, I did so with intention. I approached it with the attitude of a novice working within a set of boundaries. I took some classes and began studying painting at the most fundamental level – learning and practicing each of the basic principles of design until I gained some competency. As I could afford it, I purchased good books and dvd’s by master artists – not just to add them to my library, but to use them as textbooks and teachers. Most of all, I practiced and practiced what I learned and gradually saw my work improve. Rather than stifling my creativity, I found the principles I was learning served to liberate it.

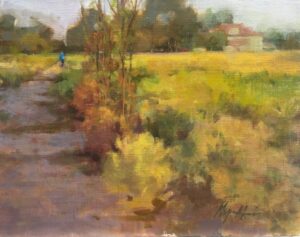

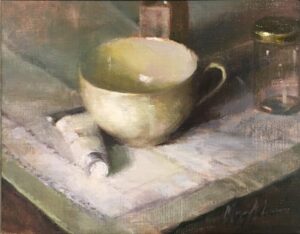

by Megan A. Lewis

The learning process can be frustrating, but the reward of finally grasping a concept is amazing. It’s like finding the key to a long- locked door. I remember the day I understood how to use color temperature to achieve the illusion of light and form. I was painting a lichen-covered branch. “Eureka!” I thought, “I finally get this!” One door that stayed stubbornly locked for years was in the area of design. No matter how much I had learned about composition, those bits of knowledge were not enough to really crack the code for me. It was earlier this year, in a workshop with John Lasaster, that the pieces finally fell into place and I came away with understanding and tools I could use!

I like the term “artistic journey”. If you look at it as a journey, you’ll keep moving forward and your work will get stronger. If you look at it as a destination, you might put down roots too soon and miss out on all the potential waiting down the road.

I will quote Edgar Payne in

closing:

“When the artist has schooled and disciplined himself to the point where he can respond to natural impulses, the real enjoyment in painting begins.”