“1970 Plymouth Fury Gran Coupe”

by Alden Jewell

licensed under CC BY 2.0

Remember paisley? I do. My brother had a 1971 Plymouth Fury Gran Coupe with a paisley vinyl top. It was a boat of car like those behemoths you’d see in Dirty Harry movies. It looked like a family man’s car. Like something, an accountant might drive to the office. But underneath the reserved styling was a pure 1960’s muscle car. Lots of horsepower and very fast. And, oh, that vinyl top! The paisley was brown on brown and smartly understated. Just enough to add a decorative flair. But not so much that it attracted too much attention to itself.

Enough about the car. Let’s talk about what paisley has to do with painting dappled light! Paisley is an intricately woven pattern of tear drop shapes. It originated in Persia in the 3rd century. Before gracing vinyl roofs on cars, it was an ornamental textile design. The shapes themselves can be long and narrow, short and wide, big or small. For me, the beauty of paisley is that it appears to flow randomly across whatever it’s used to decorate. It’s utterly designed in a logical repetitive fashion that feels random and conveys movement. Lots of movement. And that’s where the connection to dappled light comes in.

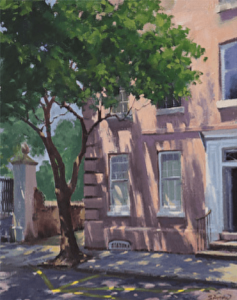

When painting dappled light we shouldn’t blindly try to copy our reference. We should take advantage of the opportunity to design a more interesting pattern than nature sometimes gives us. One that intentionally moves the viewer’s eye in orchestrated fashion through the painting. That’s what I did in “Charleston Charm”. The flow of light filters through the Crepe Myrtle onto the wall in an interlocking pattern of jagged shapes. It moves from upper left to lower right. When the light contacts the sidewalk the pattern angles back toward the left, leading the eye to the yellow parking stripes on the street which direct the gaze back to the upper left and the viewer’s path begins anew. With each circular pass through the painting more interest is discovered; the door, the railing, the post on the left and so on. But it’s the seemingly random pattern of interlocking light and shadow shapes that generates all the movement.

20″ x 16″ – Oil

Available at Reinert Fine Art

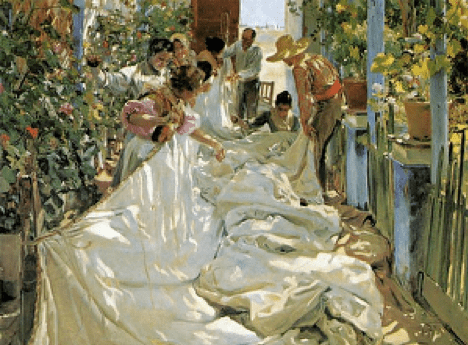

The best example may be “Mending the Sail” by Joaquin Sorolla. Truly one of the all-time Tour de Force masterpieces, this huge painting features a seemingly random pattern of dappled light. At 7’3″ x 9’10” this is certainly not an alla prima painting where Sorrolla observed the pattern of light and painted what he saw. Surely, he observed this scene or something very similarly. And he must have done preliminary sketches and studies. But no doubt he did a fair amount of designing the pattern of dappled light. Why wouldn’t he? It lends itself so well to helping direct the path a viewer’s eye would take. And therein lies one of the least discussed, yet most important skills a painter can possess, the ability to orchestrate movement.

I’ll discuss that subject in depth in my next article. But for now, let’s take a quick look at how Sorolla used dappled light to help move the eye through “Mending the Sail”. There are other very powerful compositional elements here, but the pattern of light certainly plays a prominent role. The strong vertical pattern of light and shadow to the left, just beneath the woman in pink, grabs the eye pulling it into the heart of the painting. It moves the gaze downward toward the folds below. Then the eye meanders along the spots of light on the folds until it reaches the figures on the right. And suddenly the strong verticals are repeated in the silhouetted chair behind the older gentlemen. The gaze catches the heads and faces and more dappled light on the left and makes another pass spiraling outward as it goes. But it’s the dappled light that initiates all the movement. It’s a little like noticing the paisley first then the car. In that sense, both the paisley and the dappled light are functional decoration.