Often we’ll hear someone declare “I just loooove that painting.” But do you ever listen to why they’re drawn to a particular piece?

I do — frequently. Because I come right out and ask “Why do you like it?” In galleries, restaurants, online, on the street and even in taxis (cabbies love voicing their opinions!), I’ve queried people about what draws them to their favorite art.

Perhaps I seem forward, but I have an excuse. I’m an artist. I want to understand why a work of art moves someone so that I might learn something I can apply in my own painting — a quality to strive for, a nuance of emotion, a device to add to my artistic tool belt.

I believe that “good” art is more than merely decorative. While we can argue at length about what attributes make a masterpiece, one trait they all seem to share is they make us feel – even if the emotion is unpleasant.

So why do people feel passionate about a work? As you can imagine, there is no single reason. However, most replies fall into a handful of categories, which I present to you below. Now mind: This is not a list of why we should like a painting – these are not necessarily qualities that make a work profound. They are simply reasons why we actually connect to certain pieces.

You can decide if any are worth your further consideration and inclusion in your own work.

Fantasy and Escapism

Many people tell me they love a painting because it makes them happy. They want to walk into the scene. Hey, I get it. Real-life contains unpleasant things like uncertainty, rejection, loss and even violence. Wanting to forget our troubles and be transported to a magical realm is human.

This desire to escape into the canvas is the most common reason people give for loving Thomas Kinkade paintings. Cozy little cottages, in happy villages, nestled in fairytale forests – some with gas street lamps that actually light up! Who wouldn’t want to move in?

Fantasy is not limited to shopping-mall art or to the landscape genre. Highly regarded figurative work trades in this commodity too. How many of us would prefer to pull up a chair to Norman Rockwell’s Thanksgiving dinner table in “Freedom from Want” than sit at our own?

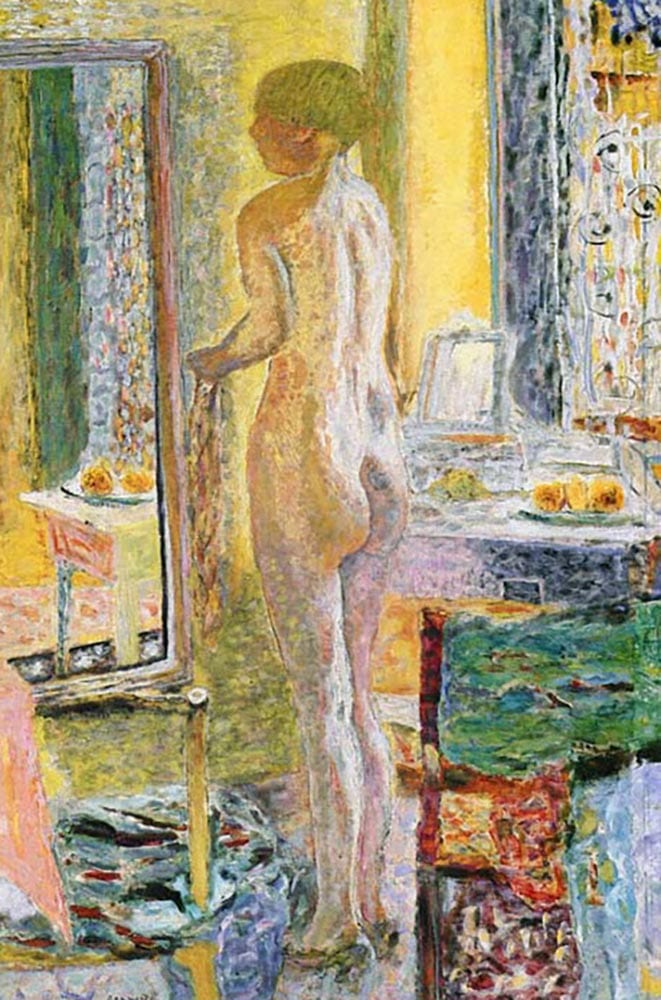

And day dreams come in many flavors. Respected living painters make careers depicting angelic milkmaids bathed in heavenly rim light, gathering water from streams. Artists past and present have painted nudes with perfectly airbrushed derrières swooning on chaise lounges. None of these scenes depicts real life, but they’re loved and collected by many.

Nostalgia

One woman I spoke to fell in love with an impressionistic painting of Carmel Mission. She and her husband had spent their honeymoon road-tripping through California, and the painting connected her to this joyous time in her life. Many of us have had a similar experience, whether as artists selling work because it sparks a happy memory in a buyer, or as a viewers of pictures ourselves.

Sometimes an abstract element in the artwork triggers nostalgia. My husband, a West Coast native, feels his homeland’s sparkling sunlight in Richard Diebenkorn’s paintings – their rectangles of light blues, tans and greens remind him of warm sidewalks, patches of neatly mown grass and glimpses of the shimmering ocean in the distance.

On an intuitive level, he understands the Diebenkorn’s Ocean Park series. Whenever he encounters one in a museum, he stops to bask in its California-ness and his eyes grow misty. (That’s when I know a trip to see the in-laws is looming!)[1]

(Note: Diebenkorn’s works are not in the public domain, so I am unable to post one. My husband has selected this William Wendt painting, which also reminds him of his homeland.)

Love of Beauty

Beauty. People either love it or they hate it. Modern art critics mock it. Most of us working in the representational genre (as well as many abstract painters) aspire to create it. To the non-art public, it can be intoxicating.

What do I mean by beauty? Well, as they say, it’s in the eye of the beholder.

For the painter, it can mean fine craftsmanship. How many times have you oohed and ahhhed over a magnificently painted hand? Or admired a color harmony so glorious it makes the back of your neck tingle? Or the one that dazzles me every time — masterfully controlled edges that play hide and seek as they lead the eye around the canvas. Many of us have purchased a colleague’s work for the sheer delight of its technical virtuosity.

The general public often sees beauty as a state of elevated “prettiness” – a decorative aesthetic consisting of uplifting colors and an overall pleasing design. A canvas that makes people smile always garners attention, and one that looks attractive in a living room quickly earns the “red dot.”

Some people find beauty in unique subjects. I know one collector who has filled his house with images of resplendent, but damaged, men. Their scars, he says, make them more attractive by giving them a humanity that resonates with his own life experience.

Human Connection

Art can also serve as a portal, connecting one human to another, sometimes over great spans of time or culture. It can do this in several ways.

Art can link viewer to creator. Looking at a work can feel like reading a “message in a bottle,” cast out from the artist to the future. No matter what subject the artist depicted, his or her thoughts and opinions — including hopes and fears — are inescapably expressed. Self-portraits can be particularly poignant: Not only are we allowed to glimpse the artist’s person, but we are allowed to see them as they saw themselves.

Some people feel a human connection with the model in a figurative work. One OPA colleague singled out a portrait drawing by George Lambert as a favorite. The model’s direct gaze and the tilt of her head spoke to him of her attitude and character. Her simple gesture, performed and recorded over a century ago, seems fresh and alive today.

Art can transport us to distant moments in history. I had the privilege of walking though the Getty Museum with a military historian. His deep knowledge of the social context in which the paintings were produced helped me see them in a new light. I remember one painting he asked to stop and view. It was a piece I had overlooked because its aesthetics did not initially grab me. Listening to my companion describe the political climate in which it was created, however, made me realize it was an image I wouldn’t soon forget.

The painting was Èdouard Manet’s “The Rue Mosnier with Flags.” It depicts a quiet Parisian street with flags fluttering in the wind. The flags mark a national holiday celebrating the country’s recovery from the Franco-Prussian War and the Paris Commune that followed. On the left is a construction site, common during the city’s transformation under Haussmann’s rebuilding. The center of interest is a man walking alone — an amputee, presumably a war veteran. The scene evokes a feeling of quiet nostalgia tinged with loss.

This painting may not be as colorful and eye catching as Monet’s depictions of similar scenes, or Childe Hassam’s NYC flags, but the careful window it provides on a moment in history, makes it profoundly affecting. My companion who had not previously seen the painting, was moved almost to tears as he studied it.

Heritage and Cultural Identity

Loving artwork that connects us to our cultural heritage is a meaningful and distinct form of human connection that I believe deserves its own category.

I follow an art collector on Instagram who is passionate about historic paintings and drawings of Free People of Color from his native Louisiana. Not only do he and his wife fill their beautiful home with these important works, but they tirelessly promote the images and artifacts of Creole culture by lending them to museums and historic sites for public viewing.

One of his Instagram posts shows an 1840s miniature portrait lovingly cradled in his hand. He says that often pieces in his collection spend significant time on loan because he believes these artworks need to be seen. He goes on to observe that images of successful people of color, in a time of slavery and institutional racism, show a powerful story of success and survival against all obstacles. He states it is his calling to honor his ancestors.

Facing the Darkness

Being human means experiencing suffering. Many people connect with art because it helps them understand and cope with tragedy and loss.

A college instructor from Wisconsin described how she was drawn to Dorothea Lange’s 1939 photo “Mother and Children on the Road, Tulelake, Siskiyou County, California.” She observed, “The harshness is difficult to look away from…it begs me to give some type of reassurance and hope.” This photo, and other works by Lange, have helped the woman understand her own mother’s experience of being abandoned at an orphanage during the Great Depression, in ways her mother was not able to speak about.

A musician from Poland told me her favorite painting is a work by Zdzisław Beksiński, referred to as “AA84.”[2] (I am unable to post the painting because it is not in the public domain. To view it, I suggest a quick Google Image search). In this somber piece, two emaciated people are entwined in an emotional embrace. It appears they have undergone a recent tragedy and are possibly in the last moments of life. Though the enthusiast agrees this is a scene of great suffering, she also finds peace in the image saying that it reminds her “in the worst moments, someone dear to us, who cares about us, can make even the biggest pain easier to bear.”

A New Way of Seeing

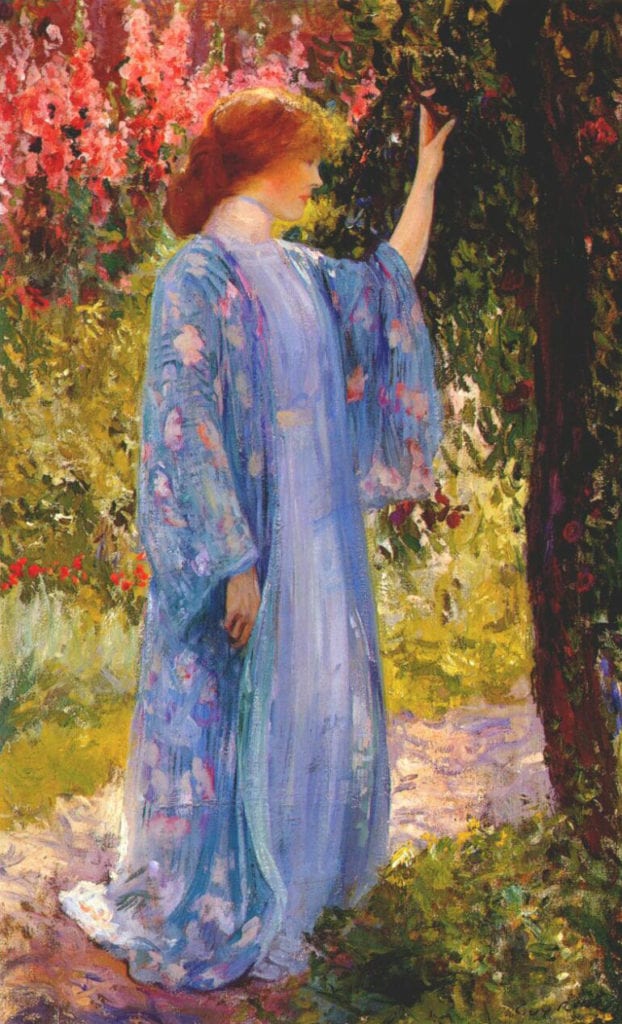

I remember the first time a painting made my heart pound in my chest. I was very young. I stood gazing at Childe Hassam’s watercolor The Garden in its Glory. In the painting, two figures stand in a cottage doorway surrounded by a chaotic, shimmering garden. Wild, slashing brushstrokes capture the sparkling light reflected off hundreds of leaves and petals.

How could a painting so precisely describe the look and feel of sunlight, while at the same time be composed of fearless marks that scream THIS IS PAINT? The push and pull between the illusion of the natural world, and the abstract qualities inherent in paint, showed me a new way of seeing. It lit a fire that I would spend the next 30 years (and counting) exploring.

Museums are filled with masterpieces that are great precisely because their creators brought people new ways of making sense of the visual world, though often our modern eyes take for granted these leaps forward. Once in awhile, however, a work will grab our attention with its new (to us) way of seeing – as Hassam’s piece did for me. When it does, even if that shift in perception is subtle, it can be life-changing.

Why Do You Like It?

I could identify more reasons why people are drawn to

favorite artworks. There’s Mood – but that’s more or less covered in categories

like escapism, nostalgia, beauty and human connection. And there’s liking a

painting for what I call its value as an accessory: when someone is fond of a

piece because of the elevated social status associated with owning it. But

Accessory doesn’t constitute a meaningful connection to art, and anyway, better

minds have already tackled the subject.[3]

So instead of examining more reasons people love certain art, I’ll pass the baton to you. What piece moves you? Send me a note and tell me why you like it. Are you affected for any of the reasons I’ve listed, or are there others you can add?

I’ll end this blog post by sharing one of my favorites. Can you guess why I like it?

[1] Diebenkorn’s works are not in the public domain, so I am unable to post one. I suggest Googling Ocean Park #79 (my husband’s favorite.)

[2] Beksiński purposefully did not title his paintings, believing that titles would unnecessarily impose the artist’s interpretation on the viewer.

[3] Tom Wolfe’s The Painted Word is a fun read, especially for those of us still tormented by the legacy of Clement Greenberg.