In this OPA blog, the issues related to using and copying the work or ideas of other artists are explored with a focus on learning. Perhaps more questions are raised than answered as they pertain to artist’s intellectual property and copyright of it.

In classroom and workshop settings, art students often learn by using the instructor’s or other artists’ work as reference for study. Copying this work may be considered “fair use”. According to the American Copyright Act (S. 107), fair use means the images may be used for learning purposes in an education, non-commercial, or non-profit setting. It may be confusing for learners to find free stock images on-line, giving them the idea that they can use or adapt the work as their own. Art instructors need to remind students that they may not sign, exhibit, or sell their studies or adaptations of other artist’s images as their own original work. It is also difficult for a student to comprehend that their work created under the direction and tutelage of an instructor is similarly, not considered original as it relates to exhibits or competitions.

This bell cannot be un-rung. Student visions of exhibiting and selling their classroom masterpieces are dashed. Hoping to gain clarity, some learners naively ask, “but isn’t the painting mine since I painted it on my canvas, with my paint?”. When it comes to copyright and fair use, the substrate or medium or who paid for it has no importance. The key for instructors is to foster student creativity and originality and to encourage that exciting moment when they can sign their name confidently to their creation as their own.

Well-meaning art groups have organized student art shows and sales to encourage and promote student learning and success with marketing. While seemingly harmless, the leaders of these initiatives need to role model that once money is involved, “fair use” ends and Copyright laws apply. Student exhibits would be more appropriate when the original work is recognized alongside the student’s unsigned projects. A name card could suffice for each student’s interpretation of the source artist’s work. Instead of sales, donations for recognition awards, prizes or art supplies could be encouraged.

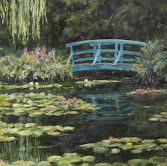

Are there any exceptions to the rules? According to the USA Copyright office, copyright protection lasts for the life of the author plus an additional 70 years. Canadian copyright laws have the same timeline. After the artist has passed away, and the timeline has passed, it is possible to use the artist’s work with care. Because the artist’s original work is over a hundred years old, it can be concluded that the copyright has expired, but there may be limitations one should always consider.

Works located in a museum are considered to be in the public domain once the artist’s copyright expires. However, museums have claimed copyright of the images they produce of their holdings, claiming talent, equipment and cost to do so. A number of court cases on this issue were reported by researcher Grishka Petri (2014). Therefore, a gallery image needs to be checked for copyright even if it appears to be centuries old if not used under the fair use clause.

It is not uncommon to see a famous image used in advertising, perhaps changed in a joking manner. Examples of famous paintings that have been adapted this way include Da Vinci’s Mona Lisa, Wood’s American Gothic, and Munch’s The Scream. Think of the Mona Lisa with glasses and a moustache. Such imitation of a style of an artist with deliberate exaggeration for comic effect or in ridicule is called a “parody” (Oxford Languages). Again, depending on the years passed or who now owns the image, it may be subject to copyright, hence the images are not shown here.

A lesser-known artistic style that imitates that of another work is called “Pastiche” (Oxford Languages). This is when various parts of another artist’s work are copied and included into a new and convincing composition. An example of pastiche in art can be seen where Michael Jackson’s face is superimposed on the famous Andy Warhol painting of Marilyn Monroe with yellow-blonde hair. On a serious note, Brittanica.com advises that when various parts of another artist’s work are copied and included into a new convincing composition it may constitute a composite fraud. In other words, the works of the original artist that are used are subject to copyright depending on age.

The most serious problem in the art world is forgery or art fraud, a criminal act. It involves passing a copy or work of the artist’s work off as created by the original artist, most typically for financial gain (Encylopedia.com). There have been numerous infamous art forgers and fraudsters over the past few decades. Some have passed off works of art they created as having been undocumented masterpieces, missing, or uncatalogued pieces from an artist’s series. One of the largest art fraud schemes in world history was recently unravelled in Canada. It involved the forgery of hundreds of works attributed to indigenous artist Norval Morriseau. Unfortunately, the effects of the fraud may have damaged the legacy of the artist.

There does not yet appear to be easily accessible or affordable technological programs using artificial intelligence to perform originality checks on artworks. Academic settings have programs to help faculty analyze student written compositions and identify plagiarism (e.g. Turnitin). Plagiarism is “Presenting work or ideas from another source as your own, with or without consent of the original author, by incorporating it into your work without full acknowledgement” (Oxford University). If we apply this definition into the work created in art classrooms, changing the word author to artist, it makes sense that students must not sign copied images as their own.

For those of us who have submitted, or plan to submit work to OPA exhibits and competitions, we must acknowledge that our work is originally conceived and that it does not infringe on copyright of any kind. OPA offers a good reminder that “It is unethical and against OPA policy for artists to submit work created from another person’s drawing/painting/photo or other artwork”. OPA firmly reserves the right to ask for proof of total copyright, indicating to members how important originality is.

To learn more about copyright and artist’s rights to intellectual property, information can be found on the Artist’s Rights Society web-site, https://arsny.com/artists-rights-101/, and the US Copyright Office website, https://www.copyright.gov/help/faq/faq-protect.html. Hopefully this blog reminds us of all these considerations, and for those of us who teach and all of us who learn, to share these important messages. As I say to my art students “If in doubt; check it out!”