In many ways, making a good painting is like walking a tightrope. The particular tightrope I’m thinking of is the one with the Abyss of Unbridled Creativity on one side and the Chasm of Static Rendering on the other.

If we ignore the gravity of technical accuracy, we risk plummeting into “There-are-no-rules-so-I-can-do-whatever-my-whims-tell-me Mode.” On the other hand, if we traverse the tightrope chanting “Paint what you see; paint what you see,” we can topple into “Gotta-get-this-right Mode” and produce cold, slavish, technical renderings.

I’ve lost my balance on both sides of this tightrope many, many times. However, I’m more prone to tumbling into the Chasm of Static Rendering, and I’d like to address this danger.

Accuracy and Vision Should Work Together

I used to think if I could “paint what I see” with 100% accuracy, I would automatically produce masterpieces. Today, I realize a good painting requires more. Don’t get me wrong, I’m not suggesting we abandon technical accuracy in the fundamentals (drawing/shape, value, edge, temperature, color). These compose the foundation upon which good representational art is built. But once we’ve laid a solid foundation, it’s time to construct the walls and roof. Truthful observation of our subject should be our primary blueprint. Yet, I propose we use this blueprint in harmony with a secondary blueprint–one I call “getting the vision.”

No, I’m not talking about anything mystical. I’m just speaking of having a clear mental image of how we want each picture to look, both before we start and as we work.

The Scope of Our Vision

Within the realm of representational art, it is vital that our vision does not take us outside the boundaries of what is visually understandable. And the only way to learn where these boundaries lie is through persistent, observant painting from life. However, that’s a different topic, and one I feel has been well-covered. Let’s focus instead on the scope of our vision, which can be broad. Our vision may affect every area of painting, including composition, choice of subject matter, technique, and even the fundamentals I listed above. That’s right, even the foundation of drawing may be manipulated slightly if doing so will serve the picture well. For example, a simple gestural line can be more expressive than an unnecessarily complex line in the subject. Asking “How can I make the best picture?” can help temper and direct our vision.

Example 1

I’d like to share two paintings that my vision affected. Please understand, I’m not encouraging anyone to paint in my “style.” I only hope you’ll ask for yourself “How do I want my painting to look?”

First is a piece that began as a few bad photos (one is below) and an even worse plein air (I’m too embarrassed to even show it). Still, I had a vision for the piece that I liked enough to attempt a small studio painting.

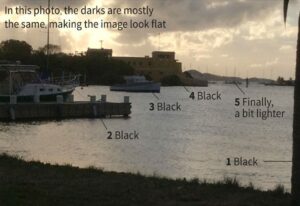

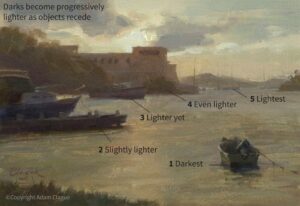

The darks in the photo below are mostly the same value, making the image look flat. To create depth, I painted the darks progressively lighter as objects receded (see painting below). My idea was based on the effect of aerial perspective—atmosphere that causes nearer shadows to appear darker and more distant shadows to appear lighter.

I also wanted to make the photo’s monochromatic color more realistic. I did borrow a few color notes from my plein air, but mostly, I made up the colors (I can hear you gasping now). Still, my color changes were based on effects I had previously observed from life. I have noticed that, when one is looking into the sun (as in this scene), there can be a glare that causes darks to appear reddish. Accordingly, I decided to replace the photo’s colorless darks with more reddish hues.

Example 2

I hope my next example will help those wondering how to paint more loosely. Classical painters, please don’t stop reading. Although I like impressionism, this article isn’t about tight versus loose painting. It’s about envisioning our pictures versus copying slavishly—I believe that applies to us all.

Loosening up starts with having a vision. How do you WANT your brush strokes to look? Look at just one small part of your subject. If you could paint that part any way you wanted, what would it look like? Get a clear picture of how you want that area to be painted, even if you can only visualize one stroke at a time. Now, pick up your brush and give it a shot. Determine to match your mental image, even if it takes several tries. Once you lay down a stroke, don’t keep blending it, or you’ll “kill” it. Rather, if the stroke needs to be adjusted, do so with a completely new stroke. Stand back ten feet. Does the area read well? If so, don’t touch it! The bravura strokes in some impressionist works might suggest the paintings were done entirely on some whimsical auto-pilot. On the contrary, loose painting is about vision and careful intent.

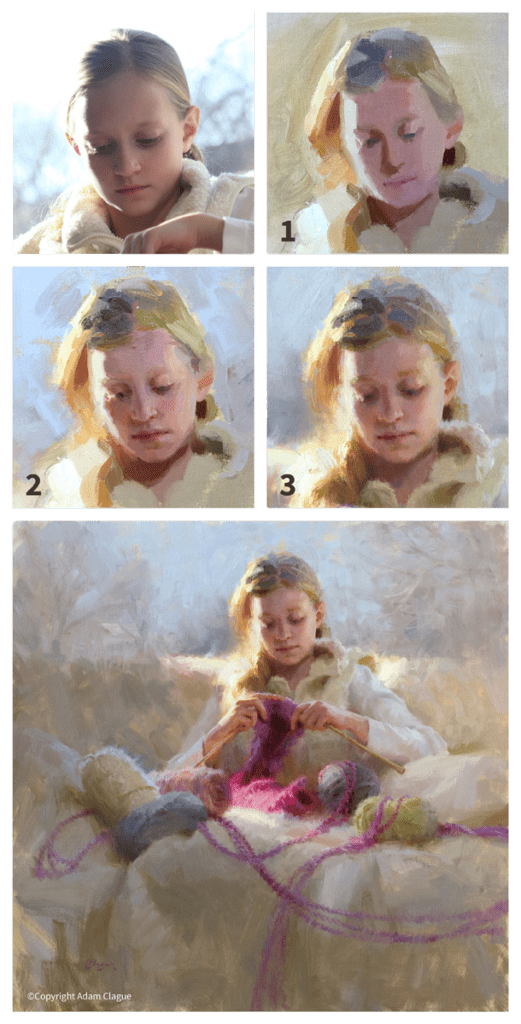

Compare the stages of the painting below. My vision was general at first and then grew gradually more specific. First, I envisioned only the basic planes of the model’s head and blocked them in (1). Next, I built upon this foundation by visualizing and painting progressively more specific shapes (2).

In the final stage (3), many of my initial shapes have been softened, but I left a few visible strokes on top for aesthetic purposes. I enjoy doing this. These strokes are usually stylized versions of the shapes in my subject, almost like little graphic designs. You can also see this tendency of mine in “Violist,” below.

Keep Your Balance

Making it across the tightrope requires a balancing pole. One end of the pole is weighted with technical accuracy and the other end with creative vision.

Don’t look down! It is scary for me to leave my comfort zone of “Gotta-get-this-right Mode” and allow my vision to inform my work. Likewise, it’s scary to admit I’ve made a technical inaccuracy. But we must do both to create our best work. To maintain our balance, we must keep our eyes fixed straight ahead (and for me, upward as well). As we take one step at a time, our paintings will begin to look more and more like how we first envisioned them.

My paintings don’t look exactly how I’d like yet, but I’m determining to press forward. I hope you’ll be encouraged to join me in walking this tightrope. I believe our best work is waiting for us on the other side.

Judy Palermo says

Thank you for a very informative article! One tendency I’m noticing in many figurative paintings, however, are the proportion problems, the clear indication and result of photo use. In your Violist painting, the arm is too massive compared to the head; if I were to imagine straightening it, it would hang much too long. Our eyes tend to automatically adjust for that when viewing photographs.

Elizabeth Whelan says

I have been interested to note, when visiting museums and seeing works by the masters, how technical reality has often been subverted for the sake of emphasis. One needs to look no further than the super-elongated humans in Sargent’s paintings for an example of this. Perhaps we place too much emphasis these days on the role photography does or does not play in the creation of a painting.

Adam Clague says

Thank you, @judypalermo:disqus, I’m glad you liked the article! Also, thank you for your comment about proportions–I’ll watch out for that!

Mary Aslin says

Great article…thanks!

Adam Clague says

Thank you, @maryaslin:disqus, so glad you enjoyed!

Elizabeth Whelan says

Very good points for us all to think about while painting; many thanks!

Adam Clague says

Thanks so much, @elizabethwhelan:disqus!

Lynette Hayes says

Adam, I have enjoyed watching your thoughts and steps with this painting. Having seen it in person, I enjoy it even more. Please keep sharing your thoughts ….technical and otherwise. Lynette

Angela Burns says

A wonderfully lucid and thorough article – thank you for sharing. I think you have it right that the two most challenging aspects of our work are in fact technical mastery and creative vision. Great article and great artwork!

Adam Clague says

Thanks so much, @disqus_MIZUz4NybP:disqus, that means a lot coming from you!

Gail Rein says

I love this article. It articulates the very issue I struggle with, coming from a very classical and literal technique and interpretation. Your painting of the knitter was one of my favorites at last years show – the photo does not do it justice of course! Thanks for sharing your insights into this ongoing challenge!

Adam Clague says

Thank you, @Gail Rein, I really appreciate that!

Sharon Will says

Hi Adam,

Excellent article! It really resonated with me. After the commercial beginnings in art with allot of rendering, I feel like I’m spending my life undoing all that. When I started painting, I was taught to learn to paint what I see. I think that is a valid first step, which I also share when teaching. But today I see that painting is really about combining what I SEE with what I WANT TO SEE. Love your work!

Michele Collins says

Thank you so much for taking the time to write these insights! I found them so very helpful. It really does take a lifetime of learning, painting, learning more, adjusting, painting some more… Your article was self-effacing & encouraging but also gave direction & guidance that each individual can use. Many thanks from Canada!

Roxanne Driedger says

This is a wonderfully helpful article. I should print it off and carry with me when I paint outdoors. I could, and will, repeatedly read the 2nd paragraph of example #2 .

You communicate your ideas very well. Thank you for sharing your insight.

Judy Palermo says

I just wanted you to know I have been referring back to your article multiple times, there is a lot here to absorb! Also the warm way you refer to processes e.g. ‘I can hear you gasping now !’ is actually quite true and familiar. I am always fighting the ‘how am I supposed to do that, was that the ‘right’ way’ etc. Your article actually helps to give some process freedom, thanks!