Ever since beginning college level art courses, I’ve been advised by my instructors to always carry a sketch book. I was a graphic design major, but was always taking drawing, sculpture, photography and countless other fine art courses. I’ve tried many times to get in the habit, but it never stuck. When I started painting 15 years ago, I felt the need for a sketch book to try and work out compositions of a scene before I started in on the painting. This time it stuck! I’ve since filled eight sketch books and this has become an essential and enjoyable part of my process in creating a painting.

Ever since beginning college level art courses, I’ve been advised by my instructors to always carry a sketch book. I was a graphic design major, but was always taking drawing, sculpture, photography and countless other fine art courses. I’ve tried many times to get in the habit, but it never stuck. When I started painting 15 years ago, I felt the need for a sketch book to try and work out compositions of a scene before I started in on the painting. This time it stuck! I’ve since filled eight sketch books and this has become an essential and enjoyable part of my process in creating a painting.

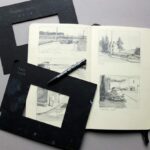

The sketch book I use is a Moleskine 5 x 8 1/4” with heavy weight paper. (Look for the periwinkle label, 104 pages) I like this one better than all the others I’ve tried. It opens flat without a spiral binding getting in the way, the size is perfect and the paper is a nice, durable weight. Very well made with a sturdy binding. I use a Cretacolor Monolith 4B graphite stick, the soft lead allowing for rich darks and loose, soft marks. And a Leuchtturm 1917 “pen loop” keeps my pencil close at hand.

My sketching routine includes the use of viewfinders which I make out of black illustration board. I have a different viewfinder for every proportion canvas I paint on. I walk around a location looking through my viewfinder until I see a combination of value shapes that looks promising. I then put my viewfinder against a page in my sketchbook, and use the window to draw a box on the page with my pencil. If I’m going to paint on an 8×10” panel, I’ll use a viewfinder with an 8×10” proportion window, thus matching that same proportion in my pencil sketch. It’s important for me to control my composition and I find this strategy very helpful.

My sketching routine includes the use of viewfinders which I make out of black illustration board. I have a different viewfinder for every proportion canvas I paint on. I walk around a location looking through my viewfinder until I see a combination of value shapes that looks promising. I then put my viewfinder against a page in my sketchbook, and use the window to draw a box on the page with my pencil. If I’m going to paint on an 8×10” panel, I’ll use a viewfinder with an 8×10” proportion window, thus matching that same proportion in my pencil sketch. It’s important for me to control my composition and I find this strategy very helpful.

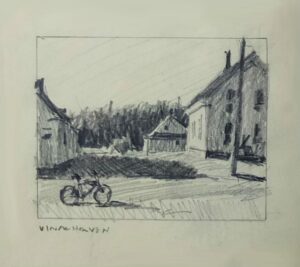

When I’m preparing to do a plein air painting, I’m always eager to get started and therefore do a loose, quick sketch for not more than 5 minutes. In the studio, working from photo references, I make a more careful drawing, spending 10 – 12 minutes. A nice pencil drawing is not my goal, so I’m careful to not get too caught up in the drawing, saving my creative, observational, right brain energy for the painting itself.

In the drawing, I’m working out compositional issues as well as trying to see a value pattern. I’m not trying to limit the number of values I work with, because graphite will give you a huge range. My effort is more geared toward establishing the light in a scene, by separating light areas from shadow areas. It also really helps to get me warmed up and engaged with the scene in front of me. No matter how long I stare at something, I don’t really see it ALL until I begin the process of recording my observations.

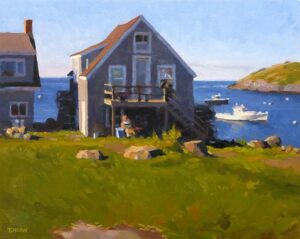

Every now and then I get a drawing that really captures the light and I’m always amazed that this can be achieved in just a quick pencil sketch. I sometimes do more than one sketch for a scene – experimenting with different compositions – but most of the time it’s just one sketch and then on to the painting. If the sketch turns out nicely, then I’m encouraged and excited to move ahead with painting, and might refer to it briefly trying to keep what it was about the sketch that appealed to me.

Every now and then I get a drawing that really captures the light and I’m always amazed that this can be achieved in just a quick pencil sketch. I sometimes do more than one sketch for a scene – experimenting with different compositions – but most of the time it’s just one sketch and then on to the painting. If the sketch turns out nicely, then I’m encouraged and excited to move ahead with painting, and might refer to it briefly trying to keep what it was about the sketch that appealed to me.

Over 15 years, I’ve filled eight sketchbooks and can say with absolute confidence that my drawing and observational skills have improved. I never draw just to draw, it is always a step in the process toward a painting. I don’t consciously work on improving my drawing, it’s just a natural byproduct of constantly being in the mode of translating what’s in front of me into marks on a two dimensional plane. Also, the great thing about doing a drawing first is that it’s ALL you’re doing. That’s it. Once you move on to the painting, numerous other issues and challenges come up such as color, value, brushwork, etc. so it’s very helpful to do this first step and simply DRAW without the other distractions.

The sketchbooks now serve as a chronicle of my life since I started painting. They place paintings in a time specific context and include street names, painting locations, names of people I met while painting, times of day and other random bits of information. They are a great reference to have and a diary of all my painting adventures over the years. I’ve thought about doing larger, more finished drawings. But for now, the sketches in the book are enough.

The sketchbooks now serve as a chronicle of my life since I started painting. They place paintings in a time specific context and include street names, painting locations, names of people I met while painting, times of day and other random bits of information. They are a great reference to have and a diary of all my painting adventures over the years. I’ve thought about doing larger, more finished drawings. But for now, the sketches in the book are enough.

Marsha Savage says

Wonderful, and good inspiration. I have many sketch books, but they mostly include thumbnails and notans… not really the way I want to use them, but I get in such a hurry to start the painting. I am trying lately to do better with drawing … actually drawing for the creating of a finished drawing. I hope this will help me translate the process to my sketchbooks. You have inspired me with your post here. Thank you.

Timothy Horn says

Thanks Marsha. Glad you found it helpful. Yes, I too am often in a hurry to get painting — especially if I’m outside. The more detailed drawings tend to be the ones I do indoors from photos when I’m less stressed for time. But I find even a quick, loose sketch helps me get warmed up for the painting.

Candace Moore says

Hi, Tim. Love your work and appreciate seeing some of your process. The pre-proportioned frames are a great tip, and my order is in for some pencil loops. I love drawing, but when I’m out in the field and those shadows start moving, I’m anxious to get some paint on the canvas. Need to take a deep breath and observe. Thanks for a valuable post.

Timothy Horn says

Thank you Candace. Yes, a deep breath is always good! My most detailed drawings take no more than 12 minutes, and I’d like to think I always have time for at least a 7 minute sketch. Many people feel that any horizontal canvas is roughly the same proportion, but I like to carefully plan where things fall in my compositions, so I find working with more precise proportions is very helpful, especially if I’m working in the studio on a larger canvas.

Before I found those pencil loops, I used to drop the graphite sticks all the time, usually resulting in a broken or shattered pencil. I got tired of trying to tape them back together!