For many years I have been inspired by the dynamic and masterful draughtsmanship of the Old Masters. Artists such as Leonardo, Michelangelo and Raphael have influenced the techniques of many artists, as their drawings have touched a very deep sense of what it means to be human. An intense study of the science of human anatomy combined with imaginative creative prowess enabled many Italian masters to communicate not only naturalness but also an intense expression of the inner human condition.

Inspired by these artistic greats, my own approach to anatomy drawing is based not only on a clinical dissection or memorization of the anatomical parts, but on a holistic interpretation of the human figure, which emphasizes the oneness or unity of forms, life, energy, and movement. While a thorough knowledge of the structures of the figure is absolutely necessary, it is only the beginning for developing works of art that can be a vehicle for expressing profound ideas and intrinsic universal concepts. Working from life is an absolute necessity for expanding one’s understanding of anatomical concepts as one can see the action of the figure and pick up on the nuances of how forms interact with each other. It also is endlessly fascinating and can alleviate the boredom that one could feel from book memorization.

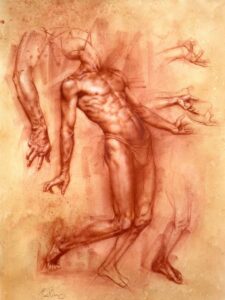

Study of Achilles, red chalk on paper

In this drawing you can see one main line of action which represents abstractly the large movement of the figure. It is a C- curve which starts at the heel of the left foot and travels up through the line of symmetry or centerline of the torso and through the back of the head. This was the first line of the sketch. I recommend that when working on any figure drawing, be sure to sense the main line of action for your pose. If it isn’t sufficient to express the gesture than you may consider changing the pose in order to make the idea stronger. In this way you can avoid wasting time on a figure that will ultimately lack emotional impact.This is an example of how my process usually starts with the largest line of movement or representation of life. Just like a flower or tree grows outward from the internal energy, so does a drawing. I then proceed to smaller rhythms of the figure to organize my structures. These larger structures will intern organize the system of anatomy including bones, muscles and tendons.

With the life and energy captured through rhythm, I then build solid structures or volumes. I recommend keeping it very simple at first. Usually only using modified cylinders, spheres, cones and boxes. You can see an example of this in the unfinished head, which has a gesture but also a simple structure. Only after understanding the fundamental structure do I proceed to modeling the more specific anatomical forms.There is great importance in emphasizing the bone structures of the figure. Know them well as this grounds the rhythms and also provides a strong foundation for the muscles.

Rendering the smaller anatomical forms of the torso, including the inter-digitation of the serratus anterior with the bundles of the external oblique and lower portion of the aponeurosis of the external oblique or inguinal ligament, became a focal point of this drawing as they fell along the main line. It is also important not to over exaggerate the symmetry of the organic nature of the muscles as can be seen in the treatment of the semilunar line or furrow between the external oblique and the rectus abdominus. Knowing the muscles intimately, including origins and insertions will give your work believability and authority. Be very careful not to treat them as bumps and bubbles, as this diminishes the natural organic quality of muscle fiber as well as the specific character of each form. In other words, don’t end up with a bag of walnuts!

Sevasti, charcoal on paper

Sevasti is one of my favorite models at Southern Atelier. A mature women in great physical condition provides an excellent opportunity for character study and to impart feeling to ones knowledge of anatomy. Though we all have the same parts, our anatomy grows with us overtime and becomes a testament to our experiences. Sevasti grew up as a trapeze artist and her body shows the years of practice and endurance she has gone through.

Notice how the entire body reflects the emotion caught in the intensity of her gaze. All of the S – rhythms of the pose seem to be leading the viewer to it. In this classic contrapposto you can see the pinch and stretch of the torso. I purposely exaggerated the fold on the left side, where the thoracic portion of the external oblique closely adheres to the form of the rib cage and the flank portion is pressed upward by the anterior superior iliac spine.

The strength of the right shoulder, including the anterior and acromial portion of the deltoid along with the acromium process also becomes very important in telling the story of the emotive impact of the figure. Its important to maintain a theme to ones figures and reinforce that idea each step of the way. This can lead to a powerful image.

Man Reaching, charcoal on paper

I learned a lot from this sketch. It was a fascinating study of a wonderfully lean model at Southern Atelier. This was the 2nd of two studies from the same angle. In the first, the arm was relaxed. Through this sketch I was learning how the anatomy of the back changes as the arm is raised. It is important to understand how one action on the figure creates reactions that reverberate throughout the body. Particularly intriguing and challenging was organizing the muscles around each scapula. Despite the complexity of the back muscles, one can still get a sense of the bones underneath.

Be sure to understand the direction of both the posterior spine of the scapula and the medial border which turns laterally when the arm is raised. Look carefully for the evidence of these landmarks. Knowledge of the purpose or action of each muscle helps in understanding what may seem as overwhelming complexity. For instance, knowing that the Acromial portion of the deltoid abducts the arm gives a reason for the volume of that form in this position. Knowing that the posterior deltoid is responsible for pulling the horizontal arm backward tells us that the muscle is somewhat flattened. Understanding the origins and insertions of the muscles is also essential for credible work. In this case, It is fascinating how one can follow the posterior deltoid as it thins to its origin on the spine of the scapula. As the arm is raised the infraspinatus can be seen.

These few examples constitute, for me personally, an exploration in the variations of anatomy; how it can create riveting art that never fails to fascinate in the process. Time and again, this search proves to be the joy of figure drawing. Many artists use a shorthand to draw the figure, which oftentimes can lead to monotony in their art. Drawing inspiration from the Old Master tradition, one can still be a modern explorer- and discover new pathways in the variation and abundance of the personification of the natural world, the human figure.

Leave a Reply