There’s always something lost when viewing a painting on a computer screen. There’s nothing quite like the luminance of a well-executed physical painting under a bright light. A sculptural impasto work can seem particularly flat without walking by it on the wall to see the light reflect off the high points and cast textural shadows.

Yet, there are some things we can do to improve the experience of viewing our paintings as screen images. Lighting can make immense changes to a physical painting and my feeling is that a screen should, as much as possible, represent a work in ideal lighting conditions. Of course, a screen image should be accurate, but if the image is accurate to the painting by candlelight, it probably won’t look as good as it could have. A viewer would then likely be surprised when seeing the physical work in better light. There are many ways for a screen image to be accurate, so choosing the best lighting condition for your painting will improve the experience for your viewer and help them understand what the work truly looks like in person.

detail

(animated image flips between even and raking light photos)

Strong light effects glow more in even light

Even light, or multiple lights from opposite directions will cancel out textural shadows and emphasize the true color mixtures of the pigments on the surface. This is great for paintings whose surface is already fairly smooth, like realist works where texture can distract from carefully painted lighting effects or rendered forms. But a richly impastoed painting will lose all of it’s sculptural qualities in this light.

Raking light, or lighting from one direction, closer to the plane of the painting surface, will cast shadows from the thick strokes and surface textures, allowing a screen viewer to experience some of a work’s three-dimensional qualities. Depending on the brightness and distance of the light source, as well as the size of the painting, exposure may need to be adjusted on one side of the image to even out the brightness. But for a thick, impasto painting, the result will be a better representation of the physical artwork. However, textural shadows in the lightest areas of a painting (often painted as thick, opaque, lights) can be problematic for experiencing the glow of a well-captured effect of strong light. A deep canvas texture can also be distracting from a work that would better viewed in even light, both in person and on screen.

In person, a painting can be seen from different angles or in multiple lighting conditions. In even lighting, three-dimensional textures can still be discerned by moving around a work. Some works are both textural and depict luminous lighting effects. So, to help a viewer more fully understand the reality of a painting, I sometimes supply images in both of these lighting conditions.

18″ x 24″

(animated image flips between even and raking light photos)

6″ x 8″

(animated image flips between even and raking light photos)

20″ x 24″

(animated image flips between even and raking light photos) Impasto is lost in even light, but preserved in raking light

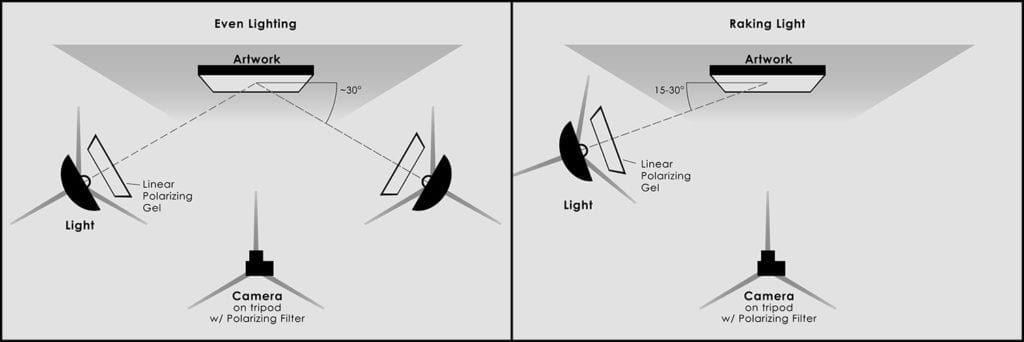

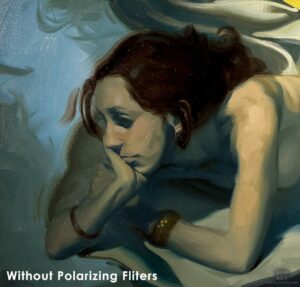

Glare is another pitfall of photographing oil paintings, particularly textural ones. A tiny bit of glare can help show texture without being too much of a nuisance, but I prefer to let raking light shadows fill this role and remove glare entirely. In person, we have the ability to remove glare by changing our vantage point relative to the lighting, but it doesn’t matter where you move your head in front of a screen, the image won’t change. To control glare, I use linear polarizing gels, or filters, over my lights and a polarizing filter on my camera lens. With these filters oriented (rotated) properly, virtually all glare can be easily eliminated from photographs of your paintings. The lighting gels on their own cut down on glare significantly so I leave them on my lights while I paint in the studio too. Polarizing film can be purchased by the foot from polarization.com significantly less expensively than you can buy individual gels from a photography equipment supplier, though you’ll probably want to purchase a camera filter from one of these suppliers.

18″ x 24″

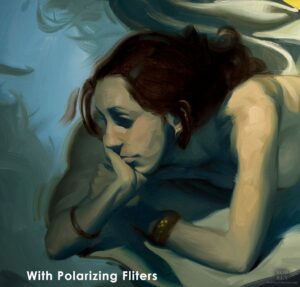

Without Polarizing Filters

18″ x 24″

With Polarizing Filters

Screen representations will always have their limits, but with the right lighting we can give our viewers the best possible, and most accurate experience.

Rob Rey OPA

Brenda Orcutt says

Such a valuable and well done article Rob, many thanks!

Tom Martino says

Some great observations here! I take special note since my own paintings often feature areas of impasto.

Shelley Breton says

Thank you so much, really helpful!

Diane Larson says

I really appreciate all this information! Thank you so much. I am looking to buy a dslr camera, I am not a photographer but I have been photographing my oil paintings with my iPhone and they do not look great! Most of my paintings have at least some impasto work in the lights.

I now know I need to buy a camera that can accept a polorised lenses cover.

Mary Rose says

Why not buy a real camera and learn to use it?