8″ x 10″

I see the world as big, abstract pieces. This painting and the colors in it are exactly how this backyard scene with a greenhouse looked to me. (Here is a photograph of the same scene).

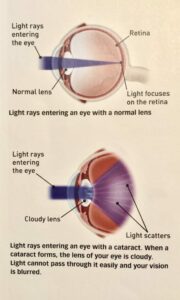

A little over a week ago I had cataracts removed from my right eye and a lens implant. (I know what you’re thinking… “But you’re so young!” Why yes I am, thank you very much for noticing.) My doctor has known me for over 30 years and has been very curious about my artist’s sight and sense of color. In fact, Dr. Gary Jerkins and I have discussed theories on Monet’s and Degas’ cataracts, something HE had studied and wanted to know my thoughts. When my cataracts very first began developing, I noticed. Seems I’m something of a little Princess actually because I had two different types. My surgeon, Dr. Rebecca Taylor, couldn’t believe I could even tell yet, as the cataracts were hardly developed at all. Most non-artists likely wouldn’t have thought anything was going on for 10 or 15 years more.

Flash forward to my post-op appointment. As soon as my doctor removed the eye patch, I could immediately tell that the left eye needs surgery too. It hadn’t been noticeable before because the right was a bit worse. The second thing I could really measure was the difference in color I could see with my new right eye. Unbelievable. I mean, these were beginning stages cataracts and I could sincerely notice the difference.

It is not uncommon for students in my workshops to challenge me on the colors I use. Oftentimes someone will say something like, “Well that’s a pretty color you used, but it sure isn’t what’s there.” I have even had students actually argue with me that I am just making up colors completely, even though I am not.

The truth, and what I try to teach them, is that we all perceive color differently. I’m not even talking about people with color blindness. I’m talking about people who see color as distinctly as you or I think that we do. What may appear as blue to you could appear green to someone else. It makes sense that this certainly happens easily between colors that are very near one another. Think of it as measuring blue-green and green-blue on the color wheel. Some people will find it difficult to tell which is which. However, many other factors can also play a role in perceived color difference.

Credit: American Academy of Ophthalmology

It’s nothing new to imagine how many famous artists through time have developed cataracts. Claude Monet, for example, reportedly developed cataracts around 1912. He had been painting his waterlily works since before the turn of that century. As the cataracts progresses, so too did the colors of his paintings. His works between 1918-1922 show muddier and darker tones, larger brush strokes, and indistinct coloration, particularly the absence of light blues. According to the National Gallery, London, it is widely accepted that he also had a form of cataract removal at age 82. Some researchers believe that Monet simply decided on a stylistic change, but in his own words, he penned, “To think I was getting on so well, more absorbed than I’ve ever been and expecting to achieve something, but I was forced to change my tune and give up a lot of promising beginnings and abandon the rest; and on top of that, my poor eyesight makes me see everything in a complete fog. It’s very beautiful all the same and it’s this which I’d love to have been able to convey. All in all, I am very unhappy.” – August 11, 1922, Giverny. He wrote that “colors no longer had the same intensity for me . . . reds had begun to look muddy . . . my painting was getting more and more darkened.” He felt that he could no longer distinguish or choose colors well and was “on the one hand trusting solely to the labels on the tubes of paint and, on the other, to force of habit.”

Degas, who also developed what is believed to have been macular degeneration. According to the Vision and Aging Lab, by his forties, Degas developed a loss of central vision. Painting became even more difficult, as he was forced to paint around this scotoma. Later on, Degas had problems identifying colors and asked his models to identify the colors of his media. His vision became progressively worse, and by 1891, at age 57, he could no longer read. “I see even worse this winter, I do not even read the newspapers a little; it is Zoé, my maid, who reads to me during lunch. Whereas you, in your rue Sadolet in your solitude, have the joy of having your eyes… Ah! Sight! Sight! Sight!… the difficulty of seeing makes me feel numb.” – Degas in a letter to friend, Evariste de Valernes, Paris, 6 July, 1891.

Dancers, 1900

Rehearsal of the Scene, 1872

From 1870 until his death in 1917, Degas sought the advice of a number of different ophthalmologists. Many theories have been put forward regarding the nature of his problem, including retinal disease, hereditary degeneration, corneal scarring and age-related macular degeneration (ARM). He was diagnosed with “chorioretinitis”, a term then used commonly to describe a variety of eye conditions. Degas’ difficulty in distinguishing colours, sensitivity to light, and scotoma all point to some sort of retinal disease. It is not clear whether his retinopathy was acquired or inherited.

Just a tidbit of interesting info regarding how we see color: Cones are one of three types of photoreceptor cells in the human eye. They are responsible for color vision. It is a huge simplification for this particular post, but basically red, green, and blue. Sea creatures can see thousands or millions more colors with many more cones. Roughly 2% of females have an extra color cone. More on that in a later post.

Elizabeth Peveto says

I find this article very interesting in light of a recent radiation treatment I had on my right eye. I am wondering how it will change what I see as I paint and teach my students. So far, I see very well at a distance because of cataract surgery on my left eye. Seeing close is another problem. I see through a cataract on the right eye and see double because of the radiation treatment. I am hoping the double vision will correct with more time. It has been just 5 weeks since the treatment. This article gave me pause to think about what changes I might see as I age and will I be happy with the results that I see in comparison to what I have been doing for the past 35 years. I feel optimistic after reading this article.

Janet Anderson says

Great post, Lori. Thanks for sharing your experience and knowledge. When plein air painting with friends I am fascinated by how differently artists perceive color even when we are all trying to capture what is “actually there” as opposed to consciously employing a colorist or tonalist theory. I suppose this is one factor that allows each of us to develop our own distinctive style which is a good thing!

Mary Rose says

I think we should worry less about the eyesight of two great painters and not put our interpretation on their paintings. It is not about us and our eyes; because we have eye changes or surgery does not mean that we know it all. And that these two great painters had similar problems. Would that we could paint like they did; maybe we should focus on learning how to paint well.

Ned Mueller says

Very well said, Mary…I will leave it at that..but did at least reference a few things in a following reply.

Ned Mueller says

Very interesting Article, Lori..but I think it could be very misleading as I think how we see and think are so much more complicated than this line of thought. I believe that phsycology, philosophy, experience and knowledge have as much to do as anything in how we as artists see the world. I have been teaching painting and drawing for over 50 years and have talked to many other artists and teachers about all of this. Not to get into a real long dissertation but basically there are three stages in learning how to see or paint. The first stage a beginner generally paints what they know..grass is green, sky is blue and they think all light is warm and shadows are cool..the second stage they learn to paint what they see…that grass could be orange, sky can be turquoise, pink and that often shadows are warm and light is cool. The third stage is the best stage..one paints more what one feels and/or how they want to interpret. This is where one enhances color and values as their intentions leads them to make what they feel will work for them. Most of us get into trouble when we are trying to do the third stage without the work and struggle to learn about color, value and edges. It is a lot more complicated than just the physical aspects of the eye..that has its function…I just had cataract surgery on my right eye and waiting to have my left eye done..the main difference I noticed was that with the new lens in the right eye..things were cooler and the left eye with the worn out lens still in was more yellow. In all due respects I am skeptical that one would actually see those brighter colors..if that was the case I would think that flourescent lights and signs would almost blow ones mind away! I do think that the more we paint the more that we see..and that also involves the area of hopefully improving our judgement. Looking forward to seeing what others have to say.

Keith Bond says

Ned, I completely agree with your thoughts.

Lori, I just wanted to add a couple things to consider.

Firstly, if someone with cataracts sees colors differently in the scene they observe, then wouldn’t they also see the paint on their palette differently too? So, in theory, if they were at the second stage Ned mentioned…trying to match the colors they actually see…then wouldn’t the perceived colors of both the scene and the painting be the same for anyone viewing the painting in relation to the scene?

If I perceived the blue of the sky to be a bit yellower than someone else, then to me the mixture on my palette would also be perceived a bit yellower than someone else viewing my palette. That mixture applied to the canvas should in theory match the way any person sees the actual sky.

I do believe that everyone sees color differently. But, if an artist is completely attuned enough to match exactly what they saw, it would be perceived as correct by anyone regardless of their personal color filtering.

This leads me to believe that there is something else at play. Interpretation of color is different than seeing color. It takes into account many other things as Ned mentioned.

Finally, one more thing, there are limitations with pigment – it is impossible to accurately match all the colors and light found in nature (especially light). The best an artist can do is interpret the relative relationships of color and value. Even at the color matching stage of artistic development, two artists might begin at a different base point to which they base the relative relationships. Both paintings look believable and accurate, but put the two paintings side by side and there will be noticeable differences in color and value.

The different starting or base point is not necessarily due to seeing differently (see my first point), but rather by how they personally responded to the scene on deeper levels.

Anyway, my 2 cents worth…

Keith

Karen says

Lori,

Excellent article. Wolf Kahn is another artist who has talked about how his developing macular degeneration is changing his work; he has embraced the physical problem as helping him to see even more abstractly. Based on my own experience with cataracts, I learned that the cloudiness can sometimes cause severe astigmatism and distortion more than affecting color perception. I had surgery a year ago on both eyes and am now happy to once again see images sharply. I concur with you that we all perceive color differently. But I have found that some teachers and painters don’t share your view. The more I paint (I have now been painting seriously for 9 years.), the more I see. Your emphasis on our individual perception is as Janet Anderson suggested what helps to shape our individual styles.

Even though I took a color recognition test a while back and scored very highly for someone with cataracts, I now wonder if my preference for yellow ochre and naples yellow were not in part influenced by the yellowing caused by my cataracts. I will have to observe my work post-surgery to see if I still have that clear preference. Eager to read more about that extra cone that some women have.

Sharon Allen says

One thing thay you don’t mention – and maybe your particular doctor dodn’t mention it – is that cataracts also come in varying degrees of darkness and can come in a (limited) variety of colors too. Very good article!