(“Madame X”) by John Singer Sargent

In the early sections of my teaching curriculum, I teach my students to make an edge chart. They start at the top by making a swatch of dark value on the left and light value on the right. These two values either separate immediately (sharp edge) or gradually, with transitional values in between the two main ones (soft edge). The first set of dark next to light swatches at the top of the chart having the sharpest break or “fence” between them, meaning the most immediate break from dark to light. Then 10 to 15 more sets are made below, getting softer as they go, with a progressively widening band of transitional values (softer edges) in between the two main ones.

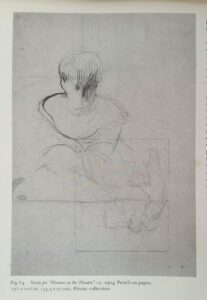

John Singer Sargent

This is just a fun way to help ingrain in the students mind that very different edges exist in the visual world as dividers of visual shapes and should exist, accurately, in their rendering of it.

Portrait Sketch by

John Singer Sargent

Joseph DeCamp

In this way he preplanned and mapped his edges before ever touching his canvas. He could then focus on the luscious brushwork that we all know and admire to convey a particular edge in a particular area. One stroke clean and sharp, another wiggled as he moved along yet another just barely scratching, scumbling a ghost of a division between two areas of value.

I try to start my paintings in this way and encourage all those that I teach to try the same. In this way we all are “aiming for the fences” in trying to “hit one out of the park” on canvas. 😉

Leave a Reply