What makes you fall in love with a piece of art? At the 2017 Cowgirl Up! show in Arizona, I was smitten with a painting by Phoenix artist Jessica Garrett. Jessica’s rosy, lit-by-the-sunrise-mountains reminded me of watching the morning sun kiss the eastern face of the Bighorns at my home in northern Wyoming. I regretted not buying the painting before someone else did. I told Jessica later how much it moved me, and she said it actually was the Bighorns (sigh). I still think of that painting.

When I read art magazines or peruse galleries and see an image I love, I try to define what artist did to make it speak to my heart. I’ve written in previous blog posts (at www.sonjacaywood.com) that my most successful paintings are honest, thoughtful attempts at expressing my feeling about a subject. This was the case with one painting last fall:

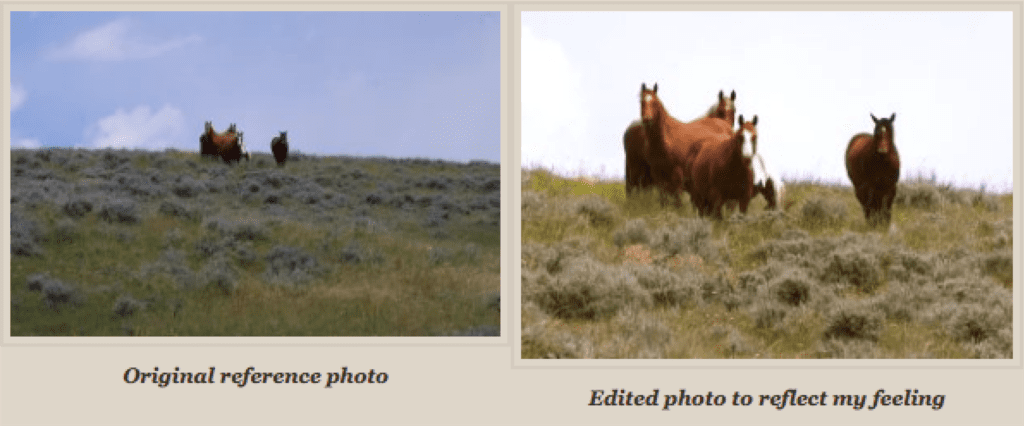

The distant “drive-by” reference photo snapped years ago from a gravel road didn’t reveal the reason I’d taken it: a group of horses were standing on a hill, catching a breeze on a warm afternoon. I remembered that they seemed “grounded” under a hazy sky, yet somehow they soared over the rest of the landscape.

I edited the photo to reflect the way the scene made me feel, and sketched it with oil and mineral spirits on a linen panel. The composition came easily, and careful but expressive strokes in dusty greens and browns brought it to life quickly. I proceeded cautiously, as when a painting’s working with a limited number of brushstrokes, I mistakenly think I’ll improve it if I keep going; many of my paintings lose their “life” in this manner, regressing from something alive with movement and space for the viewer’s imagination to “fill in the blanks” to a contrived and over-worked piece that “tells all.” I’m better at “telling-all” in print than in paint.

Pleased, but not sure it was finished, I shared the image on social media. Within hours, several people inquired as to whether it was for sale. Had I put a price on it that day it would have been a bargain, as it didn’t take long and I hadn’t fallen in love with it yet, but I chose to wait.

By the time I pronounced it “finished,” the list of potential buyers prompted me to exhibit the painting on a broader scale and to have it scanned for prints. On a whim (normally I submit more detailed, complex paintings to national shows) I entered it in my first Oil Painter’s of America National Exhibition and it was accepted! This was an enormous honor- that such a simple painting could hang with the grand, glorious works at this prestigious show makes me wonder what it communicated to the juror and the person who eventually bought it there.

Did the painting say the same thing to everyone who admired it? I don’t think so- some saw it as a rainy morning, not a hot afternoon. My husband never did like it. To me, it relayed my original impression at seeing those horses years before and also left room for others’ interpretations. This painting taught me that it’s not about replicating a photo, portraying a perfect sense of place or mood, or making a painting “look alive,” but making it elicit a “feeling” that communicates with viewers.

I hadn’t known that the mountains in Jessica Garrett’s painting were actually the Bighorns, but she painted it in a way that made me feel like I was home, marveling at my view opposite the sunrise. To perform that magic, she must be inspired by a love for her subject. This is why commissions take me so long- I’ve told clients that I have to fall in love with their subject in order to make the painting “work.” I hadn’t applied it to every day studio work, but from now on I will.

24×24 – Oil on canvas

Everything works together as it should; after several months of health issues kept me out of the studio, I needed the sale more this summer than I did last fall. Besides teaching me not to sell a painting right away, this experience informs me to be true to myself at the easel: for my art to communicate effectively, I must express– in my own artistic voice- what inspired me to paint it, without the intent of moving a potential buyer or juror with flourishes of unnecessary information.

Leave a Reply