Photograph of the Val d’Orcia in Tuscany

On a clear day we may be able to “see forever,” but as we see in this summer photo of the Val d’Orcia in Tuscany, the haze of earth’s atmosphere has a strong effect on the clarity of forms as they recede into the distance.

To capture effects such as this an artist can employ two interrelated theories, Atmospheric Perspective, and Mass. The concept of Atmospheric Perspective focuses on 3 components: shapes, values and colors. We are all aware that shapes appear smaller as they recede into the distance, but notice that their edges also soften; darks lighten (the value range is restricted) and colors are muted in the distance. This means that clearly-defined edges, the strongest value contrasts (white and black) and bright colors only exist in the foreground where we can clearly see details. This brings us to the concept of Mass. In a massed shape, details are restricted. When you notice the larger silhouette shape before the details, you are seeing Mass, and that’s what happens as the atmosphere become thicker. In the photo below, the early morning fog has massed the trees and distant hillside, contrasting with the clarity of the grain field, where details emerge.

The photograph was taken while walking the Camino de Santiago

I live and paint on the Big Island of Hawaii where the Kilauea volcano had created a daily haze for 3 decades until this spring. When we were downwind of the eruption, there were days when the horizon of the ocean disappeared entirely in the vog (our version of smog). So I’ve had the opportunity to observe and paint varied atmospheric effects for 38 years.

When painting seascapes, the horizon line can present a challenge. On a clear, crisp day it can appear as a hard edge, and the dark value of the ocean contrasts sharply with the light value of the sky. Hard edges combined with strong contrasts will visually come forward in space, but the horizon needs to read in the distance and not compete for attention with foreground objects. The concept of Atmospheric Perspective provides a way to control this important transition.

Another use of these two concepts is to direct the viewer’s attention within the composition. In this painting, I used the fog to mass the background trees which shifts the attention to the trapper and his horse in the foreground.

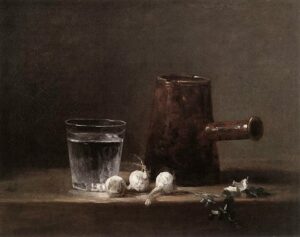

This applies to interior scenes as well. In this still life by Chardin, the edges of the table are almost lost in the atmospheric shadows except in the center foreground where it becomes an integral part of the focal point.

by Chardin

The use of deep shadows in interior scenes forms the basis of chiaroscuro, where forms are revealed in the light and fade into the obscure mass of atmospheric shadows which the masters used so effectively.

In short, as objects recede into an atmospheric space, the edges of shapes soften, the value range is restricted and colors are muted. This shifts the viewer’s attention from individual details (which can no longer be discerned) to the larger silhouette shape. So atmosphere causes objects to mass.

Leave a Reply