Corot – The Painter in Us All –

Reflections on the Master of Land and Body – By Brian Keeler

I managed to make it to the show of the work of Jean Baptiste Camille Corot (1796-1875) at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC just before it ended in December of 2018. I drove down between the holidays at the end of December because I felt it very important to see this small collection called “Corot Women” as it presented a fine grouping of his figure painting. But also, because, I have seen the other two major shows of the French Master’s work here in America. The first Corot exhibit, “In the Light of Italy” at the NGA in 1996 was an eye opener, as it served as an introduction to plein air painting in Italy and to Corot and his followers. Then, right on the heals of this show, came the comprehensive exhibit at the Metropolitan Museum in New York at the end of 1996.

Corot was not initially a favored painter of mine, an acquired taste in other words, whose work came to be appreciated rather gradually. In the show catalog for the NGA show of women, one critic of the 19th century found Corot’s figurative painting and portraits to be lacking in cleanliness. The observer, Alfred Delvau was referring to the overuse of brown and went so far as to regard them as exhibiting a certain scurviness, which he thought most unpleasant to behold. We wonder what Delvaus’ model for clean color would be, perhaps Bougerau, Ingres, Gerome or the new impressionist. Well Corot certainly has had his detractors over the years. And I can relate to Delvau’s opinion somewhat, as I too, early on found much of his work to be lacking in verve, chroma and being perhaps too pedestrian and unimaginative.

I have since come around to be a fan for many reasons. Although, when people ask me about my influences, I often mention Corot, but with a proviso- that I admire and follow his motifs, abstraction, design, concepts and much more but- not so much his style, per se. This show at the NGA presented in three modest size rooms is an appreciable collection of portrayals of women that one could absorb nicely in a few hours or easily much less. While perusing the show, we reveled in these umber tones, monochromatic studies, and of course his silvery landscapes incorporated into the compositions. The costumes of the models, often peasants in agrarian settings, and Corot’s predilection for creating archetypes while portraying individuals was absorbed too. The idea of using the model as a point of departure to create enduring and timeless personages is part of appeal here. A passage from the catalog is apropos; “Corot’s relationship with the model, seemingly as essential trigger of his inspiration, was nonetheless ambiguous. From the 1850’s on, the notion of the model who “posed” so as to be “transposed” onto the canvas by the painter would be one of the founding ideas of modernity.” We can also see his penchant for pushing the contrast and using those dark browns in the shadows of the figures and in the facial structure, as with eye sockets and cast shadows and form shadows in general.

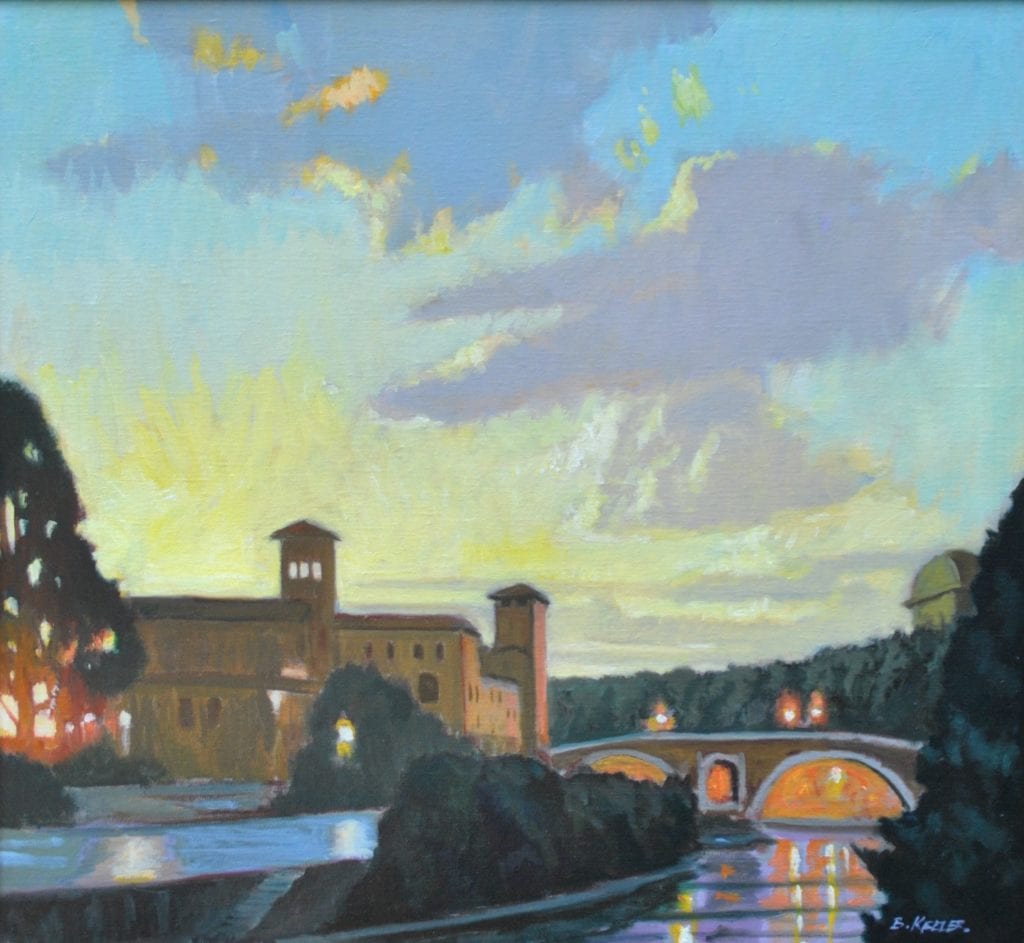

36″ x 40″ – Oil on linen

This painting, a self portrait is a studio painting but done from a spot where I worked with students that were part of my workshop. Corot also painted an oil from this location in the early 1800’s. The title refers to the placards on the opposite shore that include selections from famous Roman poets of antiquity.

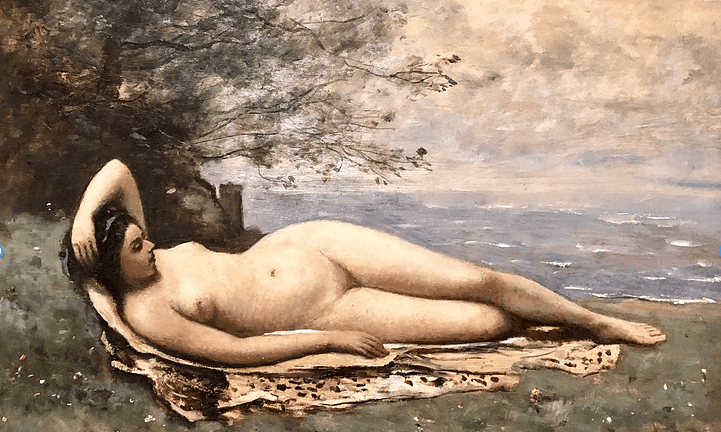

This NGA show was drawing me to it also because of its adding legitimacy to figure painting and painting the nude. I reveled in the official attention and scholarly ink being spilled on portrayal of the human form through this show. Corot’s figure work is supposed to comprise only about ten percent of his work, with his landscapes taking up the bulk of his ouvre.

As an artist, I am thinking of the process and interaction of model and painter. When I see these models depicted in nature I marvel at how they are incorporated into the settings. But I wonder if many were in fact done in the studio or perhaps a hybrid process. Either way these Corot nudes show a well-conceived blending of the genres of landscape and nude. There is mention of this fusing of genres in the essays for the catalog. An excerpt from Sebastien Allard’s essay is worth quoting here. “The reader in the background creates a sense of depth. Attenuating the regularity of the parallel trunks and forestalling any effect of a nude against a painted backdrop. With this composition, one of the most accomplished he ever executed, Corot attained a level of equilibrium and perfection that is a high point in the centuries-old quest to fuse the figure in its surrounding space.”

We can see why Monet revered Corot and how Monet’s nudes in dappled sunlight show a debt to the older Frenchman. I refer to Corot as a proto-impressionist, as his work anticipated the airy attention to the light of Monet. So its great to have these large figurative allegories available in the show to see how he worked these plein air studies into major works. For example, the Diana and Acteon canvas is one, and just down the museum hall in another room is a large landscape in the permanent collection of the NGA of a stream in Fontainbleau with a woman reclining while reading. It is truly a lovely piece (shown below) with the beautifully rendered trees and the woman comprising only a small portion of the canvas, to suggest the relative scale of nature to the human element. The depth and spatial relationships of the work should be appreciated too. And that glowing warm light, a palpable feeling for a French summer is experienced through this painting. Nicely overlapping major forms, like the masses of tree foliage lead us back into the atmospheric sfumato of the distance.

These women are lovely evocations of the mundane and the archetypal as he often makes allusions to classical mythology. The mundane aspect comes in to play in these everyday representations of the studio. Variations on a woman at an easel with a mandolin offer a very matter of fact portrayal of the artist’s studio. Done without sentimentality or embellishment they show matter of fact records done without any exaggerated color. In other words, they employ his characteristic limited palette of umbers. But they do however offer an allusion of sorts to suggest the nature of music and painting and the relationships and corollaries between the two.

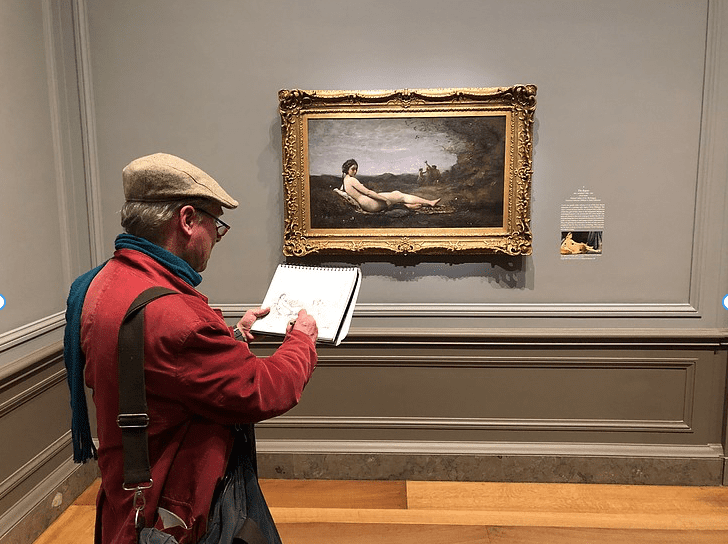

Visiting the actual paintings in the museum we can love the lush paint quality in many of these figures, clothed or nude, for his brushwork and tactile nature of the paint does draw our attention – as we are enticed to look at paint for its own sake. This is to say, that the thick impasto passages or these thin washes in backgrounds can be appreciated for the technique and beauty of paint regardless of the subject depicted. For example his modeling on the nudes can be observed to be comprised of subtle brushstrokes that are left to be unblended. I frequently take the time to sketch while I am visiting museums as it allows time to take in so much more than a cursory pass through will afford.

26″ x 30″ – Oil on linen

This painting was done plein air on location in Rome from Ponte Palantino, a bridge crossing the Tiber River. The view is of the same bridge, Ponte Fabricio and the Tiber Island buildings that Corot painted in 1825.

I have made Corot’s plein air painting in Italy a source for my own motifs for many years. In the catalog for the Met show there are maps included that showed where these landscape subjects were located. So, over the years, I’ve managed to paint at the same locations as Corot used for quite a few of his canvases in the early nineteenth century. Corot’s painting of the Tiber Island in Rome titled the “Island of San Bartolomeo” is one of those exquisite little masterworks that shows a simplified geometric design and light, yet is an honest record of the scene. I have painted this view as well, although the exact same vantage that Corot used is no longer available. Still this bridge, Ponte Fabricio dating from 63 BC and the medieval buildings on the island have changed little. Therefore they offer a timeless sort of motif.

Corot’s little brushy studies of the Roman Campania and scenes in Rome, like oil sketches of the Roman Forum and other buildings have long appealed to me, and many others. The honesty and directness of the work is part of the appeal and the unadorned impressions of fleeting light are part of the ingredients that allure us. There is a little study in the Frick Museum in New York of the Arch of Constantine in Rome that appears so simple and brushy, yet exhibits a sophisticated design that betrays its apparent slapdash nature.

Another Corot Motif that I sought out after hearing from Jack Beal, the late American painter who I was taking a workshop with, told an animated account of his visiting the bridge, Ponte Augusto that Corot had painted also. Beal, while visiting the site in Italy, became livid at the incursion of factories in this upper Tiber valley over the centuries and his wrath coincided with an earthquake in this Umbrian locale. There are two paintings by Corot of this subject that have become rather iconic and emblematic to painters. Their significance is in the fact that there is a small on-site plein air of the subject and large studio canvas. They show the importance and relevance of plein air studies to his ambitious allegories.

I like Corot’s work too in part because he is not exactly a household name, although for artists and historians his work cannot be overstated in terms of significance. For example, in the NY Times review of the Met show in 1996 there is a quote form Monet included. Monet said, “There is only one master here: Corot. We are nothing compared to him, nothing.” So we get the exalted nature that Corot was regarded with to the Impressionists and many others. In the accompanying text (wall labels) and catalog essays there is much credit given to Corot in influencing modernist or premodern painters like Cezanne, Braque, Picasso and Manet. We can especially see the influence of Corot on modern figure painters like 20th century artist, Balthus. Corot’s influence is also obvious in the umber toned still lifes of Braque and in the expressions and deep modeling and even the eyes of Picasso’s female portraits.

We can see Corot admiring his predecessors, as we are in turn, being inspired by him. For example we are directed to see how some of the poses the women assume in his paintings were derived from artists like, Titian, Ingres and Leonardo.

When I visit museums and shows like these it is always fun to find avenues of the relation and relevance. Painting the figure and portrait has been a part of my career since art school but also like Corot, a lesser-known aspect of my work. His career of over fifty years allowed him to explore these themes while growing and expanding, yet maintaining a vision and pursuit of his aesthetic. So seeing an exalted artist like Corot interpret myth, landscape, the nude and genre scenes offers a sort of validation and inspiration at the same time. He is involved in the same challenges and issues that all representational painters grapple with.

44″ x 48″ – Oil on linen

This large oil was inspired by the Greek myth and is based on several trips to the Italian Cinque Terre village of Vernazza with my students. There were plein air landscapes done at various locations here that informed this final studio work. Corot’s work with models in landscapes, also combining Greco-Roman myth or Biblical themes offered an historical precedent of this genre.

Leave a Reply