Vincent Van Gogh in the city of Arles, David Hockney in California, and Claude Monet’s extensive working excursions to the French and Italian Riviera are just a few examples of many artists who, let’s face it, were in desperate need for more sun. Van Gogh’s moody self-portraits, dark landscapes with barren or lamenting trees and paintings of furrowed faces of poverty stricken, sickly coalminers in Belgium, transmuted into a sunny and a color-saturated spectacle of exaltation during his time in the Provence.

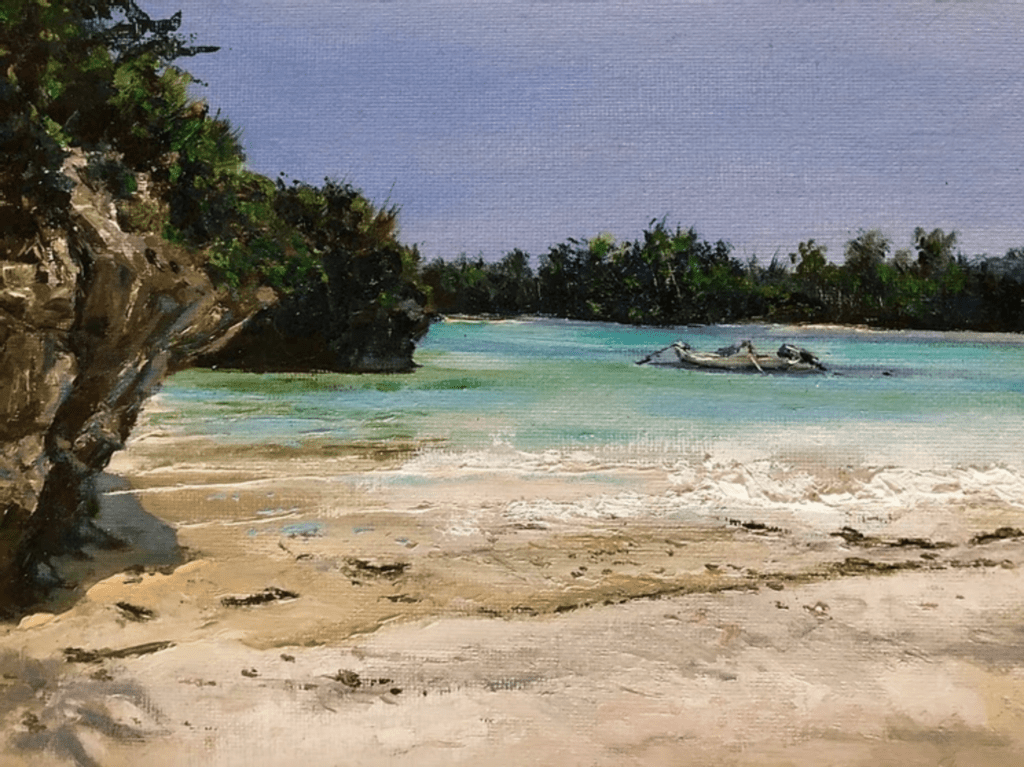

7″ x 9″ – oil

If anything is obvious, it is that light is fundamental to painters. It can be utilized to elicit mood and atmosphere, communicate symbolism, or it can draw attention to certain elements and tease out form. A painter in the Southwest has spectacularly sublime scenery and fantastic qualities of light at his or her disposal. California hills and vineyards with many warm-toned sunsets are always deliciously mouthwatering, both for the painter and the viewer. Artists located in Arizona can draw endlessly upon the phenomenal crimson and rusty red rocks, thanks to an abundance of sun-drenched days. The ideal of painting magically illuminated mountains, trees or foliage on a Mediterranean roof top terrace appeals greatly to me but less exotically, I am simply a muddy painter from a cloud-cast and rainy country called The Netherlands, or Holland as it is better known.

Growing up in the most southeastern tip of Holland in the province of Limburg, neatly sandwiched between Germany and Belgium, I had never seen clogs, let alone worn them, nor had I come across rows of tulips or Delft pottery for which my country is known. Tucked away from the famed museums of Amsterdam with works by masters such as Jacob van Ruisdael, Johannes Vermeer and Rembrandt, Limburg was and still is understated in the celebration of its local painters and art. At the foot of the Ardennes, with its rugged terrain, Limburg is a tapestry of picturesque rolling valleys, villages with half-timbered houses and meandering brooks; quite the contrast from the coin-flat polders (low-lying tracts of water embanked by dikes) of the North. As a child, my parents would regularly take me to play in the sandy dunes and run through heather-laced fields, mostly under ominous skies and never without a raincoat. At that time, and for a long time after, I was hardly aware of the many local painters in our area who had painted these landscapes and surrounding towns, in all weather, in times past.

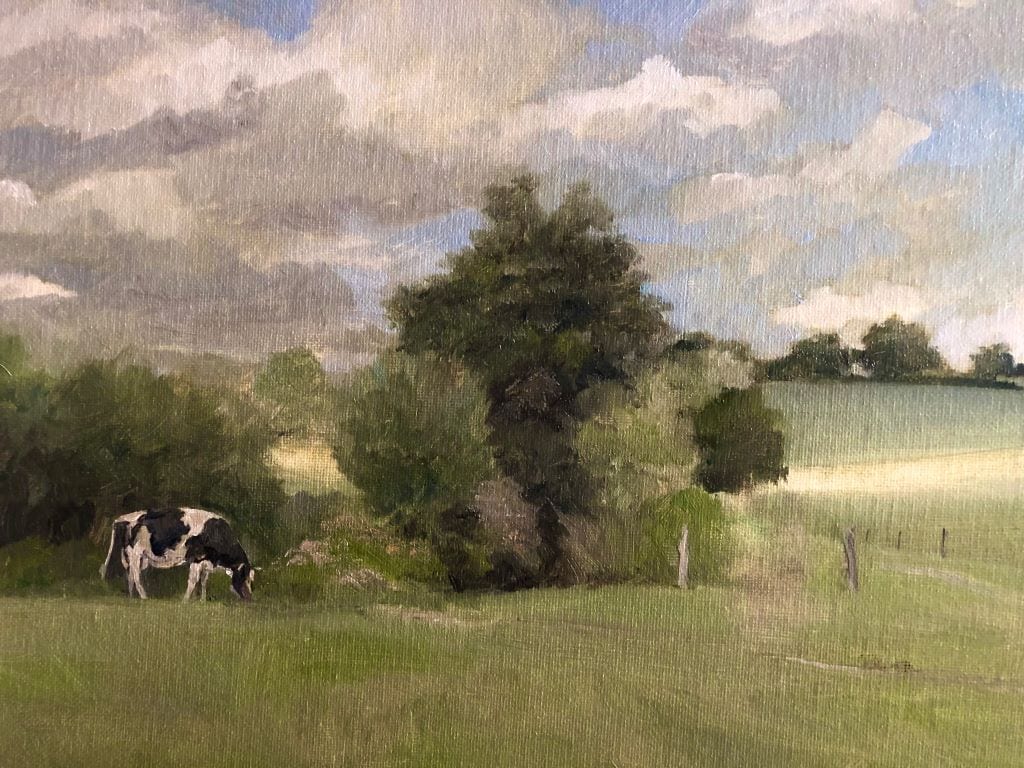

16″ x 20″ – oil

Some 25 years ago, I asked my mother about a painting of a local, dimly lit woodland with old trailers, which had been somewhat neglectfully hanging in our basement, for years. It was made with deep blues, dark browns, and ochre, vigorously applied with a wide-bristled brush in a seeming chaos of motion, with a loose yet elegantly determined finish. ‘It is by my uncle Josef, she replied casually. ‘Why did he paint?’, I asked, puzzled by this vague notion of an artist, unfamiliar to the pragmatic Dutch mindset with which the past three generations were brought up. ‘That’s what he liked to do, just like your uncle Wiel’, she said. I then recalled standing in my uncle’s dark living room, which doubled as an artist studio. His attire consisting of brown pants with old black shoes, a brown shirt underneath a brown apron against his olive skin, black curly hair and near black eyes. He could hardly be seen holding his brush in that studio. It turned out that many of my mother’s immediate and extensive family were professional artists, yet art was mostly considered an amateur or hobbyist pastime; a modest and impractical one. One could not earn one’s bread with selling art, is what was always said. As for myself, coming out as an artist was a gradual and lengthy process, mostly due to my attempts to mitigate the doubtful reservation of my practical-minded fellow countrymen, who still cannot come to terms with the fact that one can be a professional artist without completing an art academy.

32″ x 47″ – oil

Like Van Gogh and Monet, I too left behind the cold, dark and damp conditions of my native soil to find this elusive source of light called the sun. At 23, I moved to East Africa and a few years later lived in The Middle East and Southeast Asia, soaking up as many UV’s as my alabaster skin and pale canvas could handle. Finally, I was painting those blue skies, illuminated rock formations, white towns in Portugal and the bright colors of sun-kissed exotic flora on the tropical Ryukyu Islands of Japan, only to fall back in love, once more, with the gloomy towering clouds found abundantly in the landscape paintings of the Dutch Golden Age. Works by Louis Apol or Jan Van Goyen, to name just two, are totally irresistible to me, again. The unsaturated color scheme resulting from a severe lack of light tickles my fancy.

20″ x 16″ – oil

There is nothing quite like a melancholic and lonely cold Winter-scene, with people and cattle huddled together and rows of solemn trees lined up like demure dominos. Perhaps, a homecoming of early artistic influences is finding its way back into my sentiment and my work, after 20 years of transoceanic peregrinations. I am continuously drawn to those satisfyingly messy brown greens and roasted umbers. Admittedly, my palette has since been nonchalantly awash with muddy mixes, especially when painting those broody melancholic Dutch landscapes.

Perhaps it is no coincidence that my inability to paint thematically or with one identity should have coincided with my expatriate lifestyle. Of course, as a born Dutch person, I will always long for those sunny, warm locations but I am also recognizing that one’s first influences are important in understanding and reconnecting with the fundament of one’s artistic soul or source. So, I am now sitting here in my studio in Holland waiting for those drawn-out overcast days, which have not come in months. It has been too darn sunny for too long!

10″ x 12″ – oil (plein air study)

Leave a Reply