A sketch has charm because of its truth – not because it is unfinished.

— Charles Hawthorne

A few years ago, I was painting along a roadside in Wisconsin for the Door County Plein Air Festival and, while focused intently on finishing up what would certainly be seen as a masterpiece someday, I was interrupted by a young art critic who drove past and yelled out “WORST…PAINTING…EVER!”. Now, although it didn’t turn out to be the masterpiece I’d intended, I was convinced this painting showed enough promise to not be the “worst”. And honestly, if this guy had seen some of my earliest outdoor work he’d need to throw them into the mix as well and probably wouldn’t have spoken with such conviction. But all of this got me thinking – what defines our best and worst efforts outdoors? If the goal of a plein air painting is a finished masterpiece, judging the result is more straightforward. But if the goal is simply to “study” – to learn and gather information in order to develop a finished masterpiece in the studio, it’s a little more difficult to quantify the results. This is especially true if you’re like me and learn quite a bit from making mistakes. If this is the case it might just be entirely possible to paint the “Worst Painting Ever” and also have it be the “Best STUDY Ever”.

by Dave A. Santillanes OPA

oil, 9″ x 12″

by Dave A. Santillanes OPA

oil, 24″ x 30″

Although the “Back O’Beyond” study wasn’t the infamous “worst painting ever”, it definitely required further exploration. And these hurried notes became invaluable in the studio as I painted “Desert Bouquet”

THE BEAUTY OF THE STUDY

Since the time I began painting almost 20 years ago, my goal has always been simply to STUDY. To figure out exactly how nature works and translate what I’m seeing into paint. So although I joke that my aim is to paint the “Best Painting Ever Painted”, I’m hardly ever looking for a finished piece outdoors. Instead, I want to capture only the things that I can’t do in the studio – things I can’t get from a photo. I’m taking notes on color, light and atmosphere. And my focus is usually on the shadow shapes where I want to establish their exact value, color and temperature. I’m arranging those shapes to lay the groundwork for overall design but I’m not obsessing about composition at this stage – there’s plenty of time for that in the studio. In fact sometimes when I’m in the field, I’ll often ignore composition all together, especially when time doesn’t allow it… like when an afternoon thunderstorm moves in and I’m about to get struck by lighting. This might make for a bad painting but not necessarily a bad study and definitely a smart one

Once I get back to the studio where time is more abundant, I’ll take those brief, hurried notes and spend hours, maybe even days working out composition. For me, creating a painting on the spot with the same refinement as a studio piece has never been part of the plan. But, what I’ve found is that within these brief – sometimes hurried notes – occasionally a finished painting emerges all on its own. In fact, a mere study, in it’s brevity can indeed be beautiful – even beyond the beauty of a more refined piece. As Charles Hawthorne, founder of the Cape Cod School of Art once said, “A sketch has charm because of its truth – not because it is unfinished”. I think of it as “poetry” compared to a “novel” – both can be beautiful. And although it’s no use arguing this case with someone at a plein air opening who doesn’t understand why every speck of canvas isn’t covered in paint, there are plenty of examples throughout history where studies qualify as masterpieces. But this doesn’t always happen and sometimes a study is just a study. It may even be the worst painting ever.

by Dave A. Santillanes OPA

oil, 12″ x 9″

by Dave A. Santillanes OPA

oil, 9″ x 12″

The above two plein air pieces stand on their own, in my opinion, as finished paintings. I tried in vain to develop these into larger pieces in the studio but to no avail. The larger paintings used more “words” but said much less.

JUST A STUDY

And when a painting does fail miserably outdoors (or indoors) I euphemistically call it a “nice study”. If you happen to end up with one of these all is not lost. After all you’ve just spent two hours intently observing the scene… you’re now the visual expert of it. If anyone asks you a question about this place and the two hours you spent there, you have the answer. Once when I was painting near my home, four police cruisers pulled up and one of the officers jumped from his car, approached my setup and, catching his breath asks, “have you seen a short, Hispanic male with a baseball cap running through the area?” My first thought was that I fit this description precisely, but, realizing I wasn’t their suspect I was honored that they had come to me for my visual expertise on the scene. I considered offering my painting as evidence but instead just answered “No”. The point is don’t discount an intense 2-hour visual study of a scene. Many things will happen in those two hours to create the “story” that you want to tell. And be confident that you picked up a thing or two regardless of how the painting turned out. For me, once a painting falls short of my lofty visual goals, I don’t try to whip it into shape in the studio by painting over the top of it and destroying my notes (good notes or bad). And I don’t go back to the scene multiple times with the same canvas. If I return to the scene it’ll be a new attempt, a new story with a new canvas. But what I do instead is use my plein air notes and photos in the studio and seek out the good stuff. I’ll analyze the notes I got right and try to make sense of the notes that are too vague. I’ve learned that even my worst efforts outdoors contain something useful to help read and interpret photos from the scene. There are just too many good, often unintentional, things that happen when we paint outdoors. In our haste to capture a fleeting moment or escape a coming storm, we subsequently distill the scene down to only the essential elements – elements that tell the exact story we want to tell – without all the peripheral distractions. In working fast and simplifying we don’t have time to paint the things we don’t want to or aren’t interested in painting – and that’s a good thing.

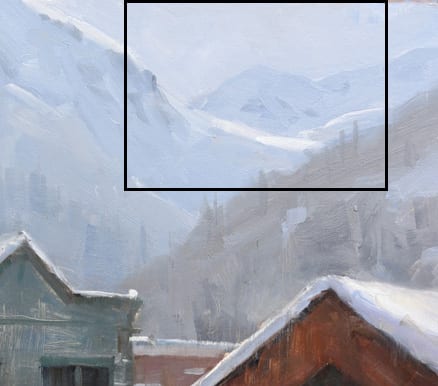

by Dave A. Santillanes OPA

Oil, 12″ x 9″

by Dave Santillanes OPA

Oil, 12″ x 9″

by Dave Santillanes OPA

Oil, 24″ x 24″

I painted “Telluride Homes” as a winter storm approached. This began outdoors as a winter storm approached. My first idea was to paint the “peaks” of the homes juxta-posed with the peaks beyond. Not a spectacular painting but a nice study. At some point during those two hours of painting and shivering, the story changed and I became intrigued with the design of light on a distant peak. “Edge of the Storm” is the finished studio piece.

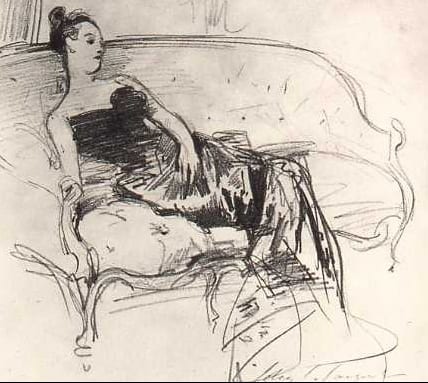

Madame X portrait

John Singer Sargent

1883 Graphite

John Singer Sargent portrait

1883 Watercolor

by John Singer Sargent

93″ x 44″

1883 Oil on Canvas

These quick sketches for Madame X might not pass as masterpieces, but the resultant studio painting certainly does.

by Dave Santillanes OPA

Oil, 10″ x 8″

by Dave Santillanes OPA

Oil, 40″ x 30″

The small study of Lake of Glass never made a direct leap to a large studio piece, but it inspired and served as an invaluable reference on several pieces, including this 40″ x 30″.

LEAVE THE FRAMES AT HOME

Ultimately what I’m saying is RELAX and remember how much fun this is. I teach several workshops throughout the year and I’m always imploring my students to leave their frames at home when we go out painting for the first time. I’m not trying to lower the bar for expectations but simply reminding them that painting outdoors is only one part of the process. The goal is, of course, to take GOOD notes as opposed to BAD ones, but it’s my way of saying don’t put too much pressure on yourself because there’s something to learn from the bad ones too. So my advice to every plein air painter is to get outside, “point to the stands” (as my friend Joshua Been is fond of saying), and paint the worst painting ever, it might just be the most valuable study you’ve ever done.

Babe Ruth pointed to the stands and then knocked one out of the park. But in painting sometimes a swinging bunt with a few errors in the field will also get the job done.

Janet Triplett says

Great article! I work very similarly outside now. I love sunsets and sunrises and my focus is to get the colors down correctly and almost forget the scene. Photos don’t give me that ahhhh… color the real thing does. Yes, they’re helpful and sometimes I’ll even use the sky study with a different foreground or scene.

Thanks for writing this!

Marsha Hamby Savage says

Wonderful conversation about the feelings of being outdoors and putting down paint. My sentiments exactly. I love the words you have chosen to use to get this point across. I so many times tell my students do not call what you are doing a “painting” until it becomes one! I also enjoy and love the word, “Study!”

Susan Drennan says

Thank you for this article. It was invaluable to my work as I have been doing 1 hour studies but for different reasons. Now when I go out to paint I will feel less pressure, and will remember all Dave has written here.

Leo Goode says

Dave, Your “Worst Painting Ever” is one of the best (blogs, that is)! I enjoyed it immensely. It’s good to be reminded of the benefits of a simple, uncomplicated, direct, honest, quick study. Thanks.

Dan Knepper says

We’ll written, Dave. You should do a book.

Bethany Hissong says

What a great reminder of what plein air can be! I think with the popularity of the movement the focus shifted from making studies to finished art and that took the fun out of it for me. I am going to approach it now as a learning experience. Thanks Dave!

Jean Ranstrom says

Although I no longer paint outdoors because of age other issues I paint in my studio.

This article gave me confidence to just paint and.TRY not to make a masterpiece but to learn something from each and every attempt! I try to search each piece to find what worked and what didn’t and to move on the the next attempt to paint the “Best painting ever” At 84 I am still learning how much I don’t know! Thank you for your words of wisdom!

Johanne Mangi says

A man after my own heart. Sometimes the hardest part is just to let go of notions. Even my “worst” Plein air pieces captivate me for a lot of reasons. Haven’t figured out how to go beyond those fresh moments back in the studio but I treasure all the information I’ve gathered.

Jeanne Kenton says

Great article. It showed both growth and inspiration. It never occurred to me to not “finish” the original study in the studio, but instead simply use it as a reference. Now I’m excited to work up a painting on a new canvas that I started on a hot, hot day and haven’t been able to make myself “fix” in the studio.

Glenn Higgins says

Excellent! I will share this with my plein air group.

George Jennings says

What Dave had to say certainly rings true with me right now.

When I decided to give up architecture and paint full time, I came right out of the shoot and into the Plein Air scene full on at a dead run. I was accepted into events and even sold some work. Other artist around me thought I was capable, and I guess I was. But I really had not defined for myself what art meant to me, nor did I really know more academically what I was doing. I had not been to art school. Typically, I was trying very hard to be accepted into a world I loved as an adolescent, but because of questionable grades and a fun high school crowd of friends, I got sent to military school! No art there!! So I was exhausting myself in an undefined goal of light and dark, or warm and cool.

Fifteen months ago I had major open heart surgery. As I have been recovering, art has only been something to observe. I was beginning to paint again with a new definition of who I am with my art, and then a major fire destroyed the town block in which my studio/gallery was located. I lost everything; over 50 years years of architectural work, and about 150 original paintings in varying degrees of completion. About 80 of them were framed. I still have 7 in the local gallery across the street from the destroyed studio, but that is the present definition of who I am in the art world. I didn’t even get away from the studio with as much as a pencil!

If it weren’t for the interest of an adorable 11 year old girl who wants me to “teach her art,” I would probably give up. But I have found that talking to her and sharing what I know and qualifying what is “feeling” and what is accepted rule of thumb law, I am still finishing and forming my former studies from the field. This wonderful young girl is pushing me to look in the mirror and decide where I am, and where I am going. Am I a study, or a work that is using the studies from the past to produce a finished work, which I now hope will never be finished.

As Dave said, we are always refining and learning from our mistakes or less successful

pieces. A quote I saw recently is what Dave and both seem to believe, “There are no failures, only lessons.” What I love about that is we can always appreciate our efforts.

Thanks Dave. I oveiously needed to deal with somethings, and you have kicked me out of neutral!

!

George Jennings says

What Dave had to say certainly rings true with me right now.

When I decided to give up architecture and paint full time, I came right out of the shoot and into the Plein Air scene full on at a dead run. I was accepted into events and even sold some work. Other artist around me thought I was capable, and I guess I was. But I really had not defined for myself what art meant to me, nor did I really know more academically what I was doing. I had not been to art school. Typically, I was trying very hard to be accepted into a world I loved as an adolescent, but because of questionable grades and a fun high school crowd of friends, I got sent to military school! No art there!! So I was exhausting myself in an undefined goal of light and dark, or warm and cool.

Fifteen months ago I had major open heart surgery. As I have been recovering, art has only been something to observe. I was beginning to paint again with a new definition of who I am with my art, and then a major fire destroyed the town block in which my studio/gallery was located. I lost everything; over 50 years years of architectural work, and about 150 original paintings in varying degrees of completion. About 80 of them were framed. I still have 7 in the local gallery across the street from the destroyed studio, but that is the present definition of who I am in the art world. I didn’t even get away from the studio with as much as a pencil!

If it weren’t for the interest of an adorable 11 year old girl who wants me to “teach her art,” I would probably give up. But I have found that talking to her and sharing what I know and qualifying what is “feeling” and what is accepted rule of thumb law, I am still finishing and forming my former studies from the field. This wonderful young girl is pushing me to look in the mirror and decide where I am, and where I am going. Am I a study, or a work that is using the studies from the past to produce a finished work, which I now hope will never be finished.

As Dave said, we are always refining and learning from our mistakes or less successful

pieces. A quote I saw recently is what Dave and both seem to believe, “There are no failures, only lessons.” What I love about that is we can always appreciate our efforts.

Thanks Dave. I obeiously needed to deal with some things, and you have kicked me out of neutral!

!

Val Sandell says

Upon reading Dave Santillanes article titled “Worst Painting Ever” I found myself smiling and nodding in agreement with his observations and opinion, delivered with engaging anecdotes. His message speaks to professionals and students equally.

When making field studies we try hard to practice everything we know within the limits of changing light. Or you have been painting a stunning mustard field for an hour at a barbwire fence on the side of the road, and the owner drives a tractor into his property and starts mowing all of it down. That one hour was not a failure to complete a “finished’ plein air, but rather as Dave says, it was successful in terms of examining and recording value, color temperature, light and atmosphere.

Karen Bakke says

Yes! Even though we go to plein air competitions to sell our studies, it is what we capture from those in-person from-life studies that are most important for our studio pieces.

Nikki Davidson says

This was awesome!! Loved every word cause I’ve been there and done that. My first outdoor exhibit I thought I’d painted a masterpiece of an Arab on a horse in the desert. As a gentlemen walked around eyeing the painting I felt sure he was going to buy it. Finally he said, ” You don’t know much about horses do you?”. Well its been 50 years and now I’m considered an expert equestrian painter but the angst I’ve always felt about that comment bugged me until today when I read this article. I am unburdened!

THANK YOU SO MUCH DAVE

Rick Rotante says

Masterpiece is just a word made up by those who don’t understand what painting is all about and need to categorize a work for value and quality. I believe DeVinci, Michelangelo and other great artists would not necessarily agree with what we determine was their greatest work. They might say they never quite achieved that one perfect artwork. Their choice might even be another piece.

Rose says

Great article Dave! Thanks for sharing your valuable insight on our plein air practice and how even our worse paintings are so valuable in our study and for our studio work. – Rose

Mike Gillespie says

Such valuable advice, and the guys yelling “worst painting ever” is one of the funniest things I’ve heard recently!

Ashlee Trcka says

Awesome blog! Lovely paintings as always from Dave and a great learning tool.

Scott Jones says

The “Best Plein Air Poetry” I have read. And I’ve read a lot. I’ll be quoting you in the future. And it explains why I have a nice collection of “worst painting ever” studies adorning the walls.

Jacalyn Beam says

Thoughtful and well written post. Thank you for sharing. I’ll Be thinking about ( and using) what you said in this post. …and saving to read again.

Stephan P Hyams says

Truer words never spoken.

Sheila Swanson says

This is a wonderful article, thank you Dave for writing it. I am a long time painter and have always enjoyed going into the field for quick studies, making color notes, a sense of place, even to the fragrance of a beautiful floral field. Memories made from a plein air outing are in my mind and certainly nudge me along as I work out a new composition in my studio.

Terry Nybo says

Dave,

This is an excellent article and perspective on what plein air painting should be all about!

joyce snyder says

This was a terrific lesson in painting and living. Thank you for it.

Ann M Lawtey says

I will undoubtedly read the article a second time. Dave including plein air studies followed by studio pieces exemplified the adage “pictures say a thousand words”.

It was a wonderful teaching article.

Thank you.

Diane E Edwards says

I just returned from a painting trip to France during which I did many “studies”. I had no interest really in finishing them, however my friends want to see my paintings! So, I am studying my studies to see where to go with them, really just will work from them instead of ON them!

Sharon Hutson says

One of the most truthful, inspiring and insightful columns I’ve read, thanks for sharing.

Pam Schrader says

Inspiring!

Laurie Hendricks says

I really enjoyed this article by Dave Santillanes. I say the same things to myself and my students when painting outdoors from life, but he put the ideas into different words creating a new perspective and providing fresh insight into the intent and result of the process of spending two hours painting a “study” outdoors vs a “finished painting”. Thank you so much!

Margaret Miller says

Once again David makes a masterpiece simply saying the vital simple notes to keep in mind when painting outdoors. I don’t bring frames with me but I do look at the scene and in my mind I try to put down what is speaking to me and when home I “study” it and try to see what I might do to capture what I saw and felt when there. Thank you David!

Gail Beveridge says

Very interesting article, Dave. I found your examples especially helpful in conveying how a study can inspire a studio painting – not necessarily by copying it but rather by taking some successful elements of the study as the focus of a studio painting or by creating an entirely new concept. When I first started plein air painting, I thought the goal was to paint a masterpiece but soon realized that, number one, this wasn’t going to happen and number two, it was okay. So I’ve learned to relax, enjoy the experience of learning to see and note the nuances in a natural setting and hopefully come back to the studio with a good study.

J says

Great article with wonderful illustrations. I love the message of making a study…not attempting a masterpiece from the start.

Mark White says

Dave’s insight is always interesting and informative. I enjoy these short ‘notes’ and the information they contain. It is a learning experience as well as inspirational.

thanks

Phil Whittington says

This was extremely rewarding for me. The learning aspect and remembering that it is in the doing and the enjoyment of where I am in the process that is the reward.

Daryl Hartman says

This is VERY helpful and instructive, with no embellishment or bull. And the images are superb examples that support what he is saying. Very well done.

Andrea Woods says

Thank you Dave for a very insightful article. Many things to put into perspective.

Irene Bailey says

Excellent

Michele de Braganca says

Great article Dave! Thanks for the reminder! I loved seeing where your “Telluride Peaks” painting came from too. Guess I’ll reconsider scraping my worst studies ever…you never know! 😁