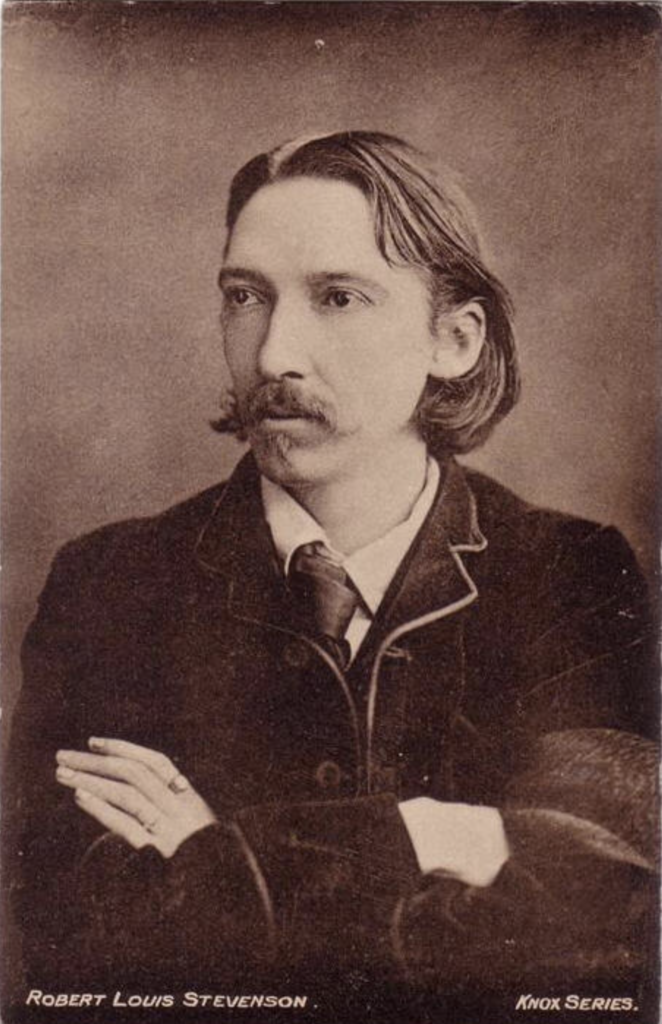

Some years ago, while raiding the family library, I came across a slim volume of essays by Robert Louis Stevenson. My grandmother had written her name inside the cover, along with the place where she was attending college: “Estella Rawleigh, Madison, Wisconsin”. Stevenson, of course, was the author of rip-roaring tales of adventure—Treasure Island, Kidnapped—but I was unfamiliar with his essays, and I made off with the book.

Well. Shiver me timbers—the essays are pure gold. One in particular I’d like you to notice. It has an awkward title, “Virginibus Puerisque,” meaning in Latin “for girls and boys,” but it’s a pure delight. It’s Stevenson’s take on men, women, and marriage, including his advice on what profession to look for in a spouse. Painters rate highly among the marriageable vocations, according to Stevenson (my emphasis in italics):

The practice of letters is miserably harassing to the mind; and after an hour or two’s work, all the more human portion of the author is extinct; he will bully, backbite, and speak daggers. Music, I hear, is not much better. But painting, on the contrary, is often highly sedative; because so much of the labour, after your picture is once begun, is almost entirely manual, and of that skilled sort of manual labour which offers a continual series of successes, and so tickles a man, through his vanity, into good humour. Alas! in letters there is nothing of this sort. You may write as beautiful a hand as you will, you have always something else to think of, and cannot pause to notice your loops and flourishes. . . . [But] a stupid artist, right or wrong, is almost equally certain he has found a right tone or a right colour, or made a dexterous stroke with his brush. And, again, painters may work out of doors; and the fresh air, the deliberate seasons, and the “tranquillising influence” of the green earth, counterbalance the fever of thought, and keep them cool, placable, and prosaic.

What do you think—is painting “highly sedative,” the sort of labor “which offers a continual series of successes, and so tickles a man, through his vanity, into good humour”? Does painting out of doors provide a “tranquillising influence”? For my part, the “continual series of successes” that Stevenson speaks of has eluded me for more than twenty years. There’s little that’s “sedative” or “tranquillising” about painting outside—it’s exciting—yes, certainly—and rewarding and addicting, but hardly sedative.

Stevenson wrote his essay a few years before John Sargent, a classmate of Stevenson’s cousin at the Atelier Carolus-Duran in Paris, painted the author and his wife Fannie in 1885:

Stevenson later described Sargent’s painting:

It is, I think, excellent, but is too eccentric to be exhibited. I am at one extreme corner: my wife in this wild dress, and looking like a ghost is at the extreme other end: between us an open door exhibits my palatial entrance hall and part of my respected staircase. All this is touched in lovely, with that witty touch of Sargent’s: but of course it looks damn queer as a whole.

In fact, there’s little about this painting that strikes me as sedative or tranquilizing. It’s dynamic and awkward and restless—and that’s what makes it great. I’d like to believe Stevenson would revise his opinion of painters after this experience.

Mary Aslin says

What a great essay you have written for us! I love Robert Louis Stevenson’s writing and this painting by Sargent. Thanks for the juxtaposition of both here to shed greater light on these two geniuses!

Wilma says

Not sedative at all. He likely nailed Stevenson as a restless soul. His wife appears as only a place to pile the fabric, rather retiring and not important. Possibly how Stevenson saw her?

Kristin Hosbein says

Stevenson clearly didn’t understand the angst that comes along with staring at a blank canvas, or fighting the biting flies or sudden storm that comes along while in the throes of plein air painting. Is it possible that he admired Sargent so much that he romanticized the profession? The painting that Sargent created is incredibly odd, and not typical, so it does lead one to ponder the thoughts behind it. Great read! Thanks, Stuart.

Cedar Keshet says

Thanks for the investigation on Stevenson and Sargent. Seems to me that Sargent has gotten to the heart of the personality of Stevenson. And that is why Stevenson is uncomfortable with it. Hard to see yourself flayed open in paint.

The painting is a masterpiece in its execution, wit and uncanny ability to give us, even almost 140 years later. We can see his wife’s languid pose, barefoot and passive, which can be read as that or also as someone who has had it with the writer’s manic manner. We can also see the writer’s nervous energy propelling him away from his spouse yet we know he will turn around in a quick gesture. Whether to rush out the door to the street, up the stairs or back to interact with his wife, we are left to wonder. But the face picking nervous energy is clear.

David Henderson says

So to the point of our painting at all. I can only speak for myself, but beyond the initial inspiration, whatever that may be, follows a journey of many struggles and mini victories through which the final painting will emerge. With inception, I can feel many emotions as an idea percolates, but as the work unfolds there comes a calmness, even a sort of warmth as I watch what started as an idea, evolve into reality. It’s an emotion I don’t quite achieve with other things.

Sargent has the great skill of taking what could be called a snapshot, and bringing it to life. I think this painting of Stevenson is just that, a moment captured, and with Sargent’s handling becomes something timeless. I would love to know how Sargent felt about this painting.

Ann Watcher says

I love this article and Stevenson’s portrait.

I agree that painting outside is often not sedative.

Richard Crawford Laurent says

I’ve never found painting to be sedative!

The subject of Sargent’s painting, Mr. R.L. Stevenson, appears to be exiting the room during this ‘sitting.’

I had one experience with a sitter. As I began a painting of my father-in-law as ‘laborer’ for an AFL-CIO sponsored exhibition at Chicago’s Cultural Center, he suddenly bolted out of the room when he realized that I was painting him. He had the strong hands of a carpenter, and he like to wear his lucky shirt on special occasions. This was not one of those occasions. It took me a month to get these ‘props’ photographed so that I could complete my ‘Portrait.of American Labor.’ During the exhibition opening, my father-in-law stood proudly next to his portrait, gesturing to anybody who walked by.