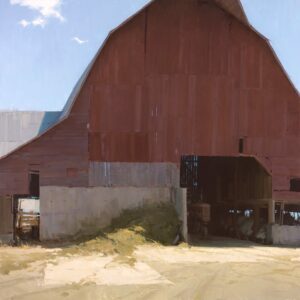

48″ x 48″ – Oil

Over the past several years I have written posts for OPA about different painting fundamentals. I would like to continue with a few thoughts on light.

As a representational painter, much of my technical work boils down to understanding how light behaves in the natural environment. Theoretical knowledge of how light works, plus observation of how these principles play out in real life, combine to provide the basis used to communicate a story, emotion, or idea (along with other design principles of course, such as composition, etc.). This concept is often put more simply as “we paint both what we see and what we know”.

Since most of us deal with the concept of light in our paintings, I’m sure these ideas are neither new to you nor novel. And it’s perfectly okay if you think about light in a completely different way (that can be fascinating). But sometimes hearing a familiar idea stated in a new way can expand our understanding.

With all of this in mind, I would like to share a few perceptions of how I think about light as a painter:

PRIMARY LIGHT SOURCE AND SECONDARY LIGHT SOURCE

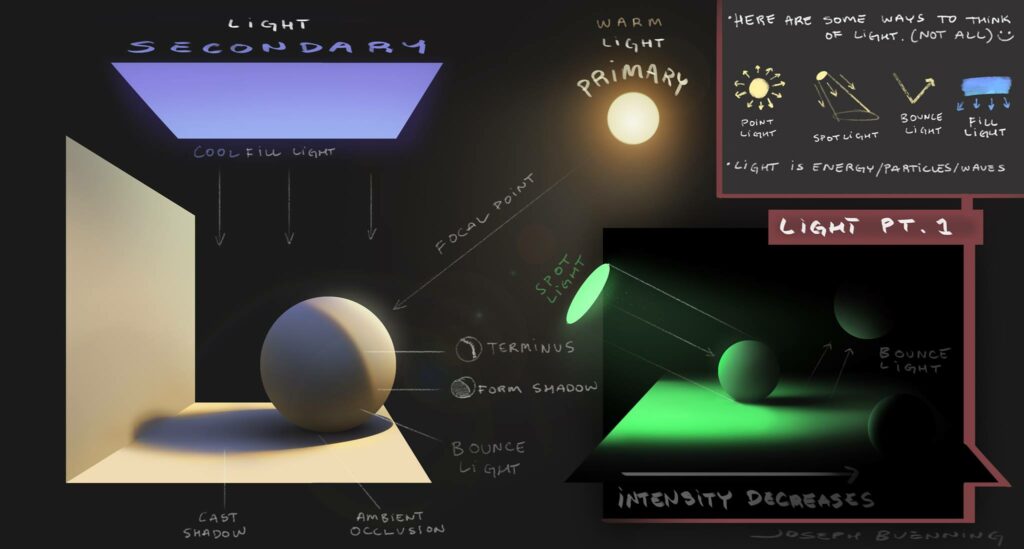

The interplay (push-and-pull, tug-of-war, etc.) between these two forces is nearly always at play in nature. Understanding how the two interact within a scene is the key to understanding the color theme or ‘thrust’ of a piece. Typically, the sun is the primary light source and the sky is the secondary source, but that can be different depending on other factors (for example indirect light, moonlight, car lights, etc.). Multiple secondary sources can definitely exist simultaneously (such as street lights, house lights, moon, etc.), but I find that these usually need to be simplified to a dominant secondary light source (i.e. choose one). One of the only places where there is no secondary light source influence is in outer space (though sci-fi artists usually cheat and add one anyway). Thus, even in small and subtle ways, most things in nature have a gradient of value and color as they get either further away from, or closer to, the primary light source and consequently more or less influenced by the secondary source. That’s a heady way to say that, on a sunny day, the surface of an object is either being hit by sunlight, or it’s being influenced by whatever else is in the sky.

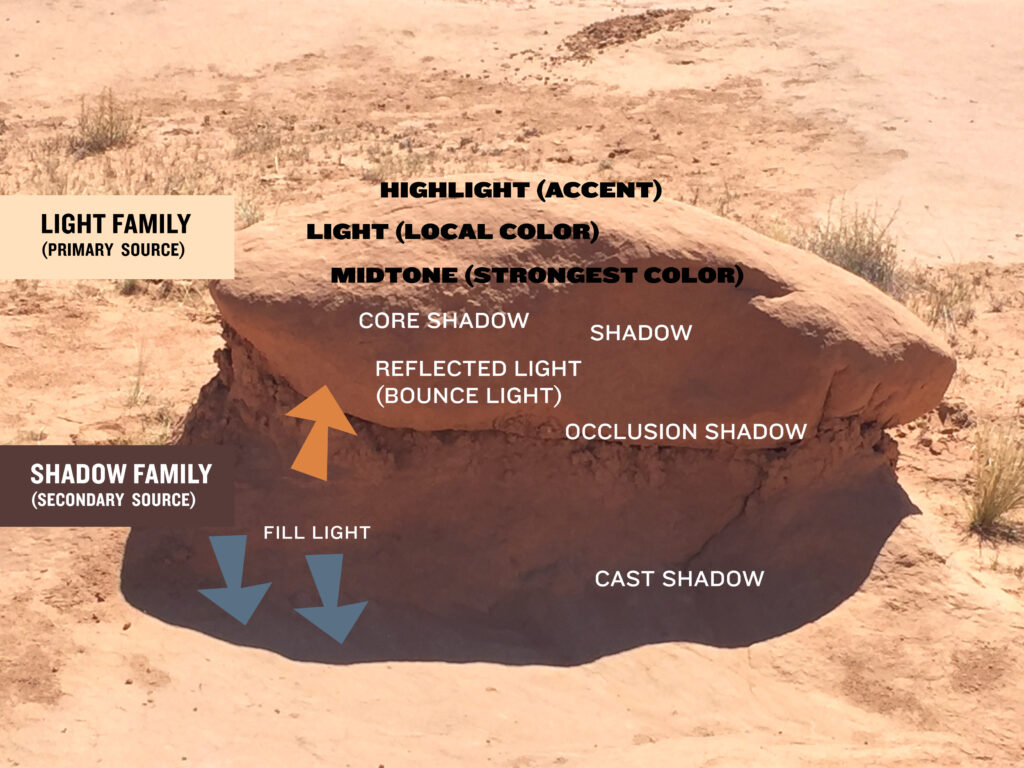

WHEN THERE IS A PLANE CHANGE THERE IS ALSO A CHANGE IN VALUE AND TEMPERATURE

This seems obvious, but it can be both tricky to observe and easy to overstate. Sometimes the value change in a plane is so subtle that forms can be turned simply by changing color temperature. The idea is that if a plane can be observed, then it’s because it’s being affected by light and thus has a value and temperature based on either a primary or secondary light source. If that plane is less influenced by the primary light source, then it is by necessity being more influenced by the secondary light source (and vice versa). A good visual to understand this relationship was created by Joseph Buenning:

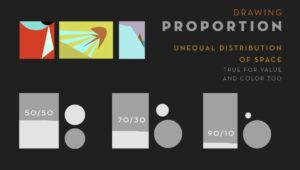

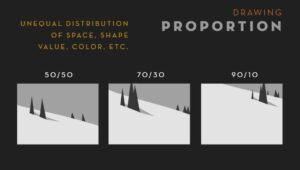

TYPICALLY, OBJECTS LOOK BETTER WHEN THERE IS UNEQUAL PROPORTION OF LIGHTING

Even if beautifully rendered, having equal amounts of light and dark in a painting is typically less dynamic and engaging then having one side of the value spectrum, or the other, dominate. (Granted, this may be more about composition, but it is important so I am including it in our discussion.) For example, when I’m walking around a tree deciding what angle to paint, I usually avoid painting the tree with the shadow right down the middle. It’s about making a choice as to what is most engaging and committing to it. My students often hear me say this boiled-down version: “Mostly light with a little bit of dark, or mostly dark with a little bit of light”.

LIGHT AND TEXTURE ARE INTRINSICALLY LINKED

How light affects the appearance of an object generally depends on the material and texture of that object. Generally, the smaller and more varied the planes of the object, the more light becomes fragmented as it bounces off, creating a matte appearance. For example, a patch of dry grass is composed of many little parts which fragment the light, giving the grass a matte appearance. The opposite is true for a flat pane of glass, which has very little surface variation, and thus appears shiny.

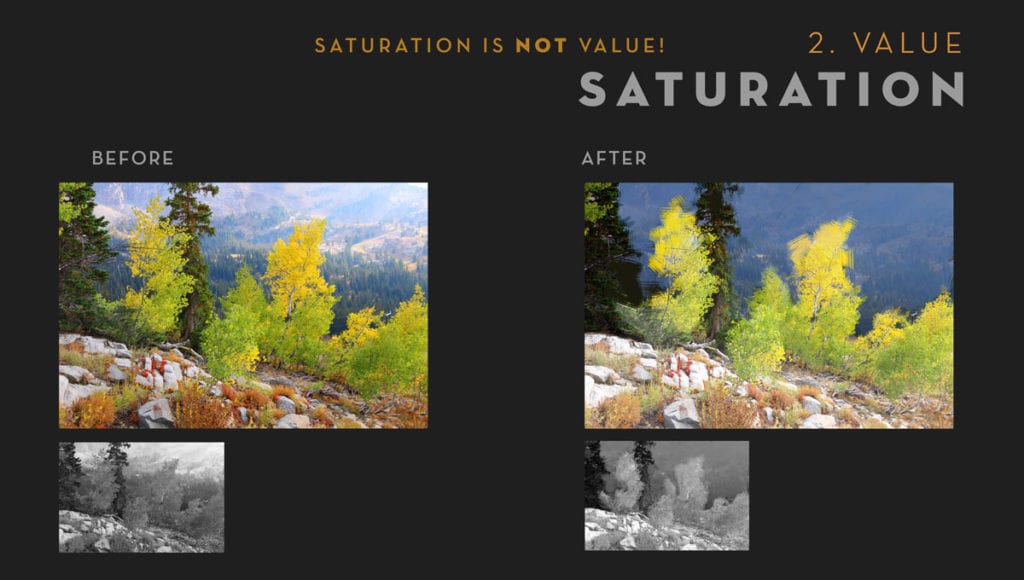

SATURATING UP THE EDGES OF A LIGHT AREA

Doing this allows one to pull back the saturation within a light area while still maintaining a feeling of vividness. This is especially helpful in areas that get really light, and due to the limitations of our paints, a choice between value and saturation must be made.

ALTERNATING OF TEMPERATURE

This can give a painting rhythm and pleasing color.

ORANGE IS THE WARMEST COLOR, AND BLUE IS THE COOLEST

The idea is that on the color wheel, either way that you shift away from Orange it cools down, and either way you go from Blue, it warms up. The same is not true for any other color. (Special thanks to William Maughan for explaining this to me once).

COLOR AND TEMPERATURE ARE RELATIVE AND BASED ON CONTEXT

Thus, “warm light, cool shadows” doesn’t mean orange and blue, it means “warmer than” and “cooler than” what they are next to. Understanding this key principle, was for me, the beginning of painting believable local color, the ability to differentiate of time-of-day, and subtle color harmony. It is the difference between having a rock that looks like it’s painted orange, and a rock that is being hit with warm light.

THE MORE INTENSE THE LIGHT SOURCE, THE MORE INFLUENCE IT HAS OVER WHAT IT TOUCHES

This is true until it eventually overwhelms a scene entirely. For example, an intense sunset is going to put a stronger wash of warmth and unifying temperature over everything than a mid-afternoon sun.

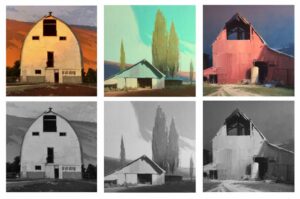

30″ x 30″ (each) – Oil

Well, there you have it. As I mentioned before, there are as many ways to think about light as there are people, and I love it when I see paintings which have approached light very differently than I have explained above (more emotionally, for example). As with most things, there is Truth, but also infinite variety and so many ways to create beauty. I wish you the best in this coming season of work, may the joy of Light fill your life!

-David Dibble OPA