Sometimes I find it hard to gather words sufficiently. But I decided long ago not to let that shut me down in speaking or writing. Thus my brief letter to you.

I like the way you lived.

1900 – 1988

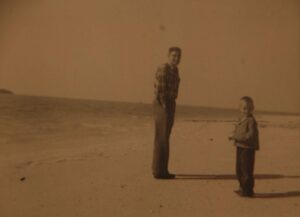

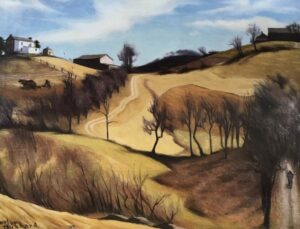

In my mind’s eye I can see you now stepping Thoreau-ish into the woods with an axe in one hand and a paintbrush in the other. That plaid flannel shirt was your go-to and there was such resoluteness in your ways. At first glance one might call you a quiet farmer. But your silence was of the contemplative nature that longed for bird song to echo around in your soul. And your farming was simply an expression of your hunger to create, as you also did with watercolors and oils. You once said, “A painting, to be good, must be done with dash and abandonment, even one which has meticulous detail. If one niggles over it, the result is dull and lifeless.”

Well, dull and lifeless you were not! After building a shantyboat out of whatever was at hand, you and Anna took years to actually float the Ohio River from Kentucky clear to New Orleans… stopping only to grow summer crops on a south-facing slope! You loved the earth and treated her as a loving mother, receiving not taking.

In your paintings I see that non-niggling dash and abandonment, sort of like author Annie Dillard describes,

Oil on Canvas,

22″ x 28″

One of the few things I know about writing is this: spend it all, shoot it, play it, lose it, all, right away, every time. Do not hoard what seems good for a later place in the book, or for another book; give it, give it all, give it now. The impulse to save something good for a better place later is the signal to spend it now. Something more will arise for later, something better. These things fill from behind, from beneath, like well water. Similarly, the impulse to keep to yourself what you have learned is not only shameful, it is destructive. Anything you do not give freely and abundantly becomes lost to you. You open your safe and find ashes.

As far as I am concerned, Harlan, you emptied your creative savings account on Campbell County Hill Farm. And for that I am indebted. You see, that’s me taking the final trek to where Papa plows the team. When I make the turn toward Dale Ridge he will see me, and I will be home.

When painters like yourself give it all, it serves us all. When artists speak story into us, it calls story out of us. When the hours of mixing and dreaming and wiping out and starting over and story-telling with your brush turns into days, you are doing a good work of inviting others like me into living more fully alive.

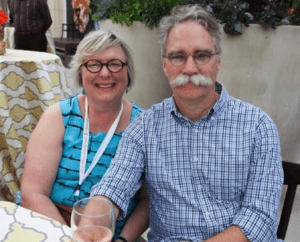

That fully-alive thing happens in me too when Kathie calls out, “I just saw something! Turn the car around!” My blood starts to pump as well knowing we just passed an old forgotten home or a partially hidden trail marked by scores of yesterdays. As I pull over I’m aware that she has already begun to shoot it, play it, lose it, all. The foot of her dash and abandonment is tap-tap- tapping against the floorboard. And it affects me as well.

Kathie Odom

Oil on Linen,

14″ x 18″

Countless times I have witnessed a sort of seed-to-fruit moment as a bystander gets caught up in the excitement of my wife bringing a blank canvas to life. Like you, Kathie wants her story- telling to come from her deepest places… all the way from her toenails, she likes to say.

The nature of the created universe is to give, not take. Hard to tell exactly what the result is from all your giving, Harlan, all your painting-what-I-feel-inside. But, whatever it is, it’s good. Give a little and more follow. And souls like mine expand on account of that giving. Yeah, that’s the end-product… an expanded soul!

And my expanded soul is grateful.

May you and Anna now somehow be creating in your rest and resting in creation,

~ Buddy

PS – Thank you, Wendell Berry, for introducing me to your good friend.

- Photo Credit: Guy Mendes.

- Annie Dillard, The Writing Life, 1989, HarperCollins Publishers.

- Campbell County Hill Farm, Harlan Hubbard, 1933, Collection of Anne Ogden.

- KathieOdom.com, 2017.

- Wendell Berry, Harlan Hubbard, Life and Work, 1997, The University Press of Kentucky.

- Kathie and Buddy Odom, Photo Credit: Amanda Lovett.