I have recently been exploring boundaries and have found some beautiful lines that are helping me to be a more thoughtful, loving artist. I’m mostly unloving toward myself, as the creator of my art; but I’m going to change that. I think that “unlove” of every sort will find its way to the canvas and spread “unbeauty” in a world that looks to artists for something higher. To help myself to grow in a positive way, I’m staking out better boundary lines between poetry and prose in my work, and art and life in my mind.

To introduce the idea of poetry and prose, I’ll share the thoughts of a writer, Ranier Maria Rilke, who wrote “Letters to a Young Poet”:

“In writing poetry, one is always aided and even carried away by the rhythm of exterior things; for the lyric cadence is that of nature: of the waters, the wind, the night. But to write rhythmic prose one must go deep into oneself and find the anonymous and multiple rhythm of the blood. Prose needs to be built like a cathedral; there one is truly without a name, without ambition, without help: on scaffoldings, alone with one’s consciousness.”

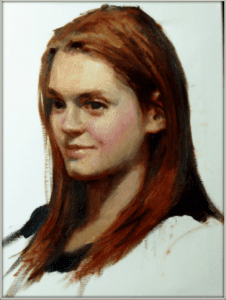

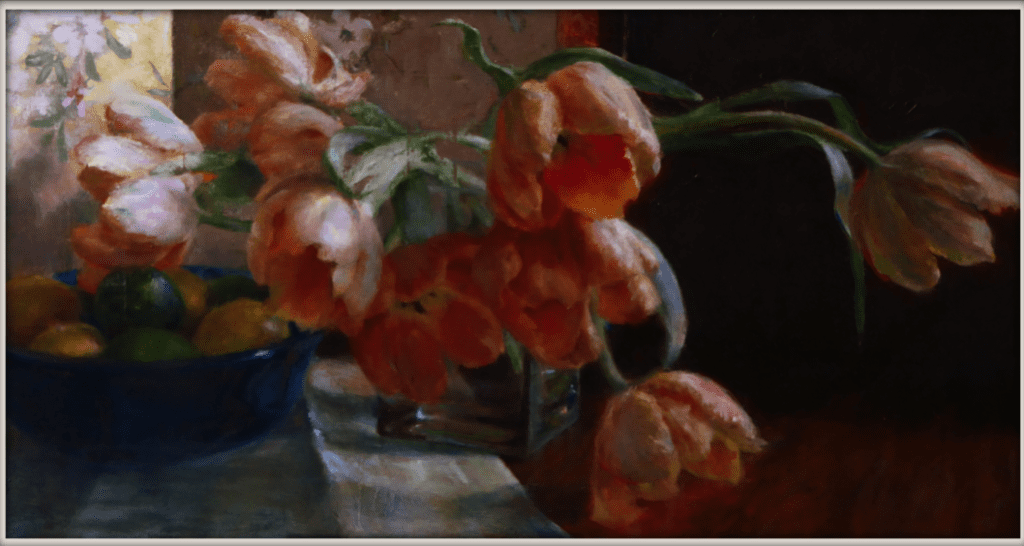

I think Rilke has drawn a beautiful, descriptive line between plein air/life study work (poetry), and the personal and important work that happens alone in the studio (prose). For us, plein air work and life study are very certainly inward-moving rhythms of exterior things; but as told in pigment instead of verse. We see and experience what is there; we learn from it and respond to it, organizing and recording the experience on the canvas. The beauty of alla prima “poetry” is that it conveys our actual experience to another person, so that they can share in—or even be shown how to see—what we have seen. It is a picture from our outside-in, not our inside-out. The more we engage in this activity, the more enabled we become to show the wonder of creation. Our lyric cadence in the field is just the same as the poets’.

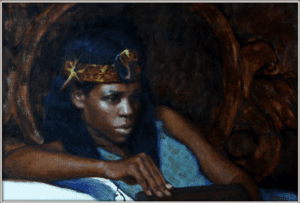

Eventually, the stimulation and inspiration that we experience as faithful reporters of what we see will cause in us a longing to express something that can’t yet be seen, that can’t be copied down from exterior things; something that is born from within our soul. This place of creation in an artist is not related to sales or art events or other artists. It’s deep. It is not conformed to the things of the outside world, but rather conforms those things to its own expression.

The whole painting may be carefully composed and drawn out before a single model is hired or reference photo found. Our “cathedral canvas” takes time, just as rhythmic prose takes time for the writer.

The reason I had to draw lines around these two is because they are two ways of working, and they result in two different products. I have been mean to myself in the past by expecting a quick cathedral. A more productive way to approach painting is to decide what your purpose is and then disallow everything that does not help fulfill that purpose. Do not be thinking of what award you’ll probably win or how much you might get for a piece while you are in your studio! That’s shallow and external and will keep you from going where you need to go, which is deep and internal. Do not expect some profound and epic masterpiece in a two hour on-the-spot painting either! You will draw your skills of observation away from the moment. In the field means in the moment. The only way to honestly and kindly explore these two types of painting is to draw and respect boundary lines and recognize when you are about to cross them.

Everything I ever learn in art turns out to be a good life-lesson for me. Lines and edges are very familiar territory to the visual artist, so one would think we’d be super good at lines and edges in life. I have found the reverse to be true with most of my artist friends, regardless of their age, gender, or level of accomplishment. What I see instead is a struggle to balance our life so that we are able to produce art. I think it’s akin to what Rilke said about prose: there is no one pre-structured way to live our life; everyone has to go deep into their own soul and spirit to learn where the boundary lines are for them.

As for myself, I normally have to use a sort of Phone-a-Friend Lifeline to find things out. Because I’m so close to it, I often can’t see the forest for the trees, which is exactly how I came to see the life-connection to this question of boundary lines in painting. I was up in the mountains, walking through the trees. I’d brought my painting gear and had some high expectations because this was new and beautiful territory. The first day I was there, I just explored. I had my camera but mostly I was just looking. I walked around this beautiful place for a long time; like maybe eight hours. I was pretty sure that where I was walking, no one had ever walked before, which gave me a funny thrill. There were new bird and critter sounds, an eagle and some hawks, wonderful marbled and weird-shaped rocks in the path and little flowers, bright leaves and puffy clouds.

I was alone as I walked, so I sang and skipped and even fell down a couple of times. I was smiling so hard all day that my cheeks hurt when I got back. But dang it! I hadn’t painted. When asked if I’d gotten anything that day, I reported that I had been scouting and had found some good prospects for the next day. But then the next day, a new and irresistible path lured me off course and there was another wonderful day of laughing out loud, climbing on and collecting rocks, getting my feet wet and figuring out which bird was singing this one song. But dang it! I hadn’t even gotten my gear unpacked. On day three, I got my gear out first thing, so I wouldn’t accidentally be wooed into fairyland again. I did not paint well. Two mediocre paintings and it was now the middle of the afternoon, so I snuck away to see if I could get to this one place that I’d seen from afar the day before.

That night, my husband asked how I’d done and I had to rat myself out. I had failed, three days in a row. (He’s my favorite lifeline—because he knows me so well, he can cut me to the quick with the right answer, delivered in just the right way.) He said, “No, seeing that as time wasted is looking at it all wrong. You are resting your mind, exercising your body, and allowing your soul to be filled up with beauty. Don’t punish yourself for that; it’ll negate the experience, and then it’s a failure.”

Artists have to allow themselves to be filled up so that they have something of substance to give. The days of joyous fellowshipping with this new place was the beginning of a conversation that would continue on canvas. I do see that it is much more respectful and real to step into a place and allow it reveal itself in stages, as you would in any new relationship. Robert Genn used to advocate sitting in a place for at least 30 minutes before even getting a pencil out, so you would know what to say about it. So clearly, for me, this place between art and life was in need of some better boundary lines. Life is to be lived well. Art is an expression of a well-lived life. If it gets muddled up and becomes my life, it will not be as rich or deep or lovely.

Heretofore, the boundary line between painting and living seemed obvious. You create art over here, and you do everything else over there. Seriously, “everything else” in my life has been pushed past that line into the “Waste of My Time” category. Not painting? Not doing your job! The line around my art life was small and heavily guarded, and the rest of my life was always a threat to its safety. But I’m now beginning to see that my painting life has to have a much bigger line around it. It has to have a reservoir to draw from and should include books and talks and silence. And no guilt. It’s a fine line, but we have to draw it. Otherwise, we will cut off the source of the quality in our work in order just to have the quantity; just the work.

Last year was my Year of Painting Fast. So far, this year is my year of finding the Power of Peace. I’m coming to see that there is a great energy in quietness, and that wonderful art can come from a restful, joyous place. Just like any good painting: there is activity and then there is a place for the eye to rest; a balance. But underneath the paint, there are fine lines of thoughtful structure, helping us to know when to turn and when stop.

At the end of Rilke’s book, there is an excerpt from a letter that I’ll close with:

“…the using of strength in a certain sense is always increase of strength also; for fundamentally we have to do only with a wide cycle: all strength that we give away comes over us again, experienced and altered. Thus it is in prayer. And what is there, truly done, that is not prayer?”

And another thing, with regard to the recreation idea. There are here, amid this realm of fields, spots of dark ploughed land. They are empty, and yet lie they here as though the bright culms round about them were there for their sakes, rows of fencing for their protection. I asked what was doing with these dark acres. They told me: c’est de la terre en repos. So lovely, you see, can rest be, and so it looks alongside work. Not disquieting, but so that one gathers a deep confidence and the feel of a big time…

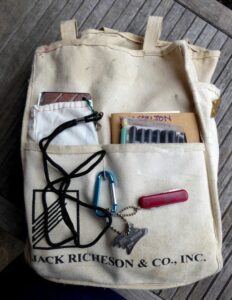

The MVP makes capturing the essence of a rapidly-changing scene much easier by literally framing and filtering it down to a wonderful design. I spent about an hour on the whole plan, including the strategy sketch and the transfer to my canvas. It’s amazing how much more smoothly the painting process goes when you have confidence in the plan and structure that underlies it. Having the right tools to simplify our job will go a long way toward the creation of stronger paintings.

The MVP makes capturing the essence of a rapidly-changing scene much easier by literally framing and filtering it down to a wonderful design. I spent about an hour on the whole plan, including the strategy sketch and the transfer to my canvas. It’s amazing how much more smoothly the painting process goes when you have confidence in the plan and structure that underlies it. Having the right tools to simplify our job will go a long way toward the creation of stronger paintings.

Here’s how you prepare your canvas: It’s easier to work on a tabletop for this than using an easel. Tape the canvas to a board to allow yourself freedom to spin the chart around as you fill the squares. Measure out a quarter of an inch for the width of the tape, then an inch for each square, and repeat for every color. Make tic marks with your pencil, rather than lines, to indicate placement. Put the quarter-inch tape between the marks and leave a tag hanging off the end for you to pull when you’re done. Place all vertical tapes first, followed by all horizontal tapes. You will carefully remove the tape as soon as you are done with each chart (don’t wait till later!); it is easy to pull the horizontals off first, then the verticals. Now write the initials of the colors you will be charting. For example, the colors I use for the limited palette are Transparent Oxide Brown, Ultramarine Blue, Cadmium Red, and Cadmium Yellow Pale: TOB, U, CR, and CY. The Transparent Oxide Brown chart will have these headings on the columns: TOB, TOB/U, TOB/CR, and TOB/CY. Note that the size of your chart/canvas will be determined by the numbers of colors and values you want to explore. For the limited palette, I chose four colors and five value steps, so I will have four across and five down, plus some space between each chart. Measure it out accordingly.

Here’s how you prepare your canvas: It’s easier to work on a tabletop for this than using an easel. Tape the canvas to a board to allow yourself freedom to spin the chart around as you fill the squares. Measure out a quarter of an inch for the width of the tape, then an inch for each square, and repeat for every color. Make tic marks with your pencil, rather than lines, to indicate placement. Put the quarter-inch tape between the marks and leave a tag hanging off the end for you to pull when you’re done. Place all vertical tapes first, followed by all horizontal tapes. You will carefully remove the tape as soon as you are done with each chart (don’t wait till later!); it is easy to pull the horizontals off first, then the verticals. Now write the initials of the colors you will be charting. For example, the colors I use for the limited palette are Transparent Oxide Brown, Ultramarine Blue, Cadmium Red, and Cadmium Yellow Pale: TOB, U, CR, and CY. The Transparent Oxide Brown chart will have these headings on the columns: TOB, TOB/U, TOB/CR, and TOB/CY. Note that the size of your chart/canvas will be determined by the numbers of colors and values you want to explore. For the limited palette, I chose four colors and five value steps, so I will have four across and five down, plus some space between each chart. Measure it out accordingly. Here’s how you create your chart: Understand that this is an exercise for your eyes, mind, body, and soul. It will demand your full involvement in a most personal way as you begin a real dialog with your colors. Give yourself lots of latitude, grace, and hours.

Here’s how you create your chart: Understand that this is an exercise for your eyes, mind, body, and soul. It will demand your full involvement in a most personal way as you begin a real dialog with your colors. Give yourself lots of latitude, grace, and hours. When you have your first and last colors laid in, you will mix the value that is right in the middle of those two. Mix it and hold it on your knife over the two color values on your chart and ask yourself which it favors more, the pure color or the lightest tint. This is when your colors really start talking to you. When you finally mix a color value that favors neither, you have your middle square. The last two colors are halfway between each of these: one is halfway between pure color and middle color value, the other is between middle color value and lightest possible value.

When you have your first and last colors laid in, you will mix the value that is right in the middle of those two. Mix it and hold it on your knife over the two color values on your chart and ask yourself which it favors more, the pure color or the lightest tint. This is when your colors really start talking to you. When you finally mix a color value that favors neither, you have your middle square. The last two colors are halfway between each of these: one is halfway between pure color and middle color value, the other is between middle color value and lightest possible value. It’s easy to see how your mind and eyes are challenged by the creation of color charts, as all the measuring is intellectual and visual. If you try to literally measure part-for-part, you will not have an accurate chart because every pigment has a different saturating power. So, your mind and eyes are about to get smarter. You will not find how it challenges your body until you start the process. You will then be amazed at how physically demanding this assignment is. This isn’t for sissies. And as for the soul… ultimately your choices, as objective as this process seems, will be determined by how you feel. It can’t be taught. You will only get it when you do it. This is why charts must be done and not just seen. It’s also why the color charts vary between different artists, and why Richard Schmid can say that he learns something new every time he makes a new set. He is still making new charts for himself! And since he’s been painting longer than a lot of us have been breathing, perhaps it really is a worthwhile thing to try.

It’s easy to see how your mind and eyes are challenged by the creation of color charts, as all the measuring is intellectual and visual. If you try to literally measure part-for-part, you will not have an accurate chart because every pigment has a different saturating power. So, your mind and eyes are about to get smarter. You will not find how it challenges your body until you start the process. You will then be amazed at how physically demanding this assignment is. This isn’t for sissies. And as for the soul… ultimately your choices, as objective as this process seems, will be determined by how you feel. It can’t be taught. You will only get it when you do it. This is why charts must be done and not just seen. It’s also why the color charts vary between different artists, and why Richard Schmid can say that he learns something new every time he makes a new set. He is still making new charts for himself! And since he’s been painting longer than a lot of us have been breathing, perhaps it really is a worthwhile thing to try.