I don’t know about you, but when I begin a larger painting I tend to start thinking of the painting as “precious” far too early. Either it is a large and costly substrate, or I get going on the painting and as it is going well, I get too worried about messing it up. Then I get into trouble by painting too carefully and the painting suffers as a result.

I use small studies to counter that.

Before we go further, I have to talk about watercolours. Yes, I know I am writing for the OPA blog, but please humour me for a minute. I started as a watercolour painter and it is on paper that I learned much of what I know about painting.

There have been a number of times on my artistic journey when I have made quick strides in acquiring better painting skills. The first time was when I got myself some better materials, switching from student-grade paint and paper to 100% cotton paper and good paint. This experience is true in any medium. If you are painting with paint and cardboard canvas panels from the craft store, you will see a change when you switch to actual linen or buy a few tubes of good quality paint.

The next artistic leap forward was when I briefly got on the daily painting bandwagon in 2013. I committed to making one small (5″x7”) painting a day for 60 days. I did it for 2 months only because I was also still working at my first career and had 2 children under 10 years old. I didn’t feel I could commit to more than 2 months.

I initially had planned it as a marketing strategy, and it worked well for that, but it ended up being far more valuable in terms of what the daily practice taught me. I ended up repeating the 60 day experiment twice more in the next two years. Each time, I found myself learning more about how to compose a painting, how to simplify, how to use a bigger brush proficiently and more about what does and does not make a successful painting.

I also learned that a painting that fails is no big deal. Rather: an unsuccessful painting was just an idea that did not work, and I would get to try something different when I painted again the next day. This gave me an unanticipated freedom from expectation. I did not have to carefully consider what subject I was going to paint because I would be painting something else the next day. This freedom let me play and it was wonderful.

I learned the value of repetition. I was publishing these paintings each day so I did want to have something to show by the end of the day. If I made one that flopped completely, I would just restart. I was painting on small pieces of paper, after all. The second attempt gave me a chance to address what I thought went wrong. This was incredibly valuable as it let me answer the question of “what if I had done this instead of that?”

Ok, enough about watercolour. This is the OPA blog after all, I should write about oil painting.

Now, years later I am also an oil painter. As I explore a new idea for an oil painting I often start with a small study. I have gotten comfortable with small square panels, 6″x6”. I like the square format because it helps to remind me that I am just painting a piece of a larger idea. I buy birch panels from a local supplier in bundles of about 20 and so I never feel like I am going to run out.

When I am painting on such a small surface I do not feel like I am taking a risk when I try something new. The little paintings don’t feel “precious”. Rather they are a place where I can play with the paint. If one doesn’t turn out, it’s no big deal at all. I do not feel I have “wasted a panel” because I have a bunch more sitting on my shelf, waiting their turn.

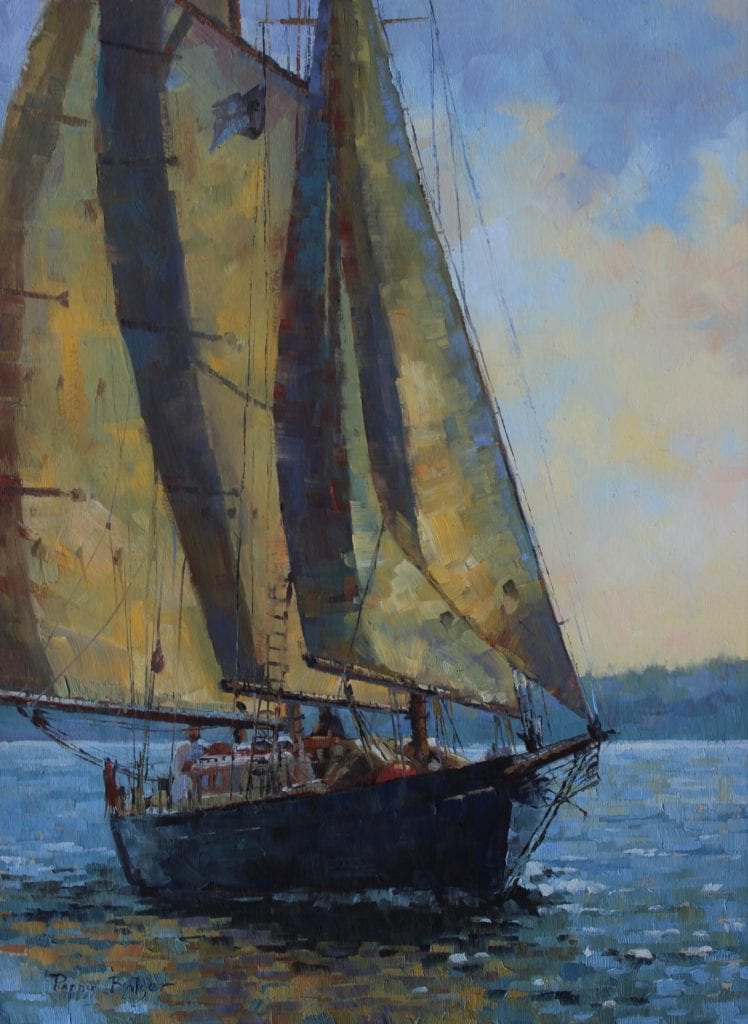

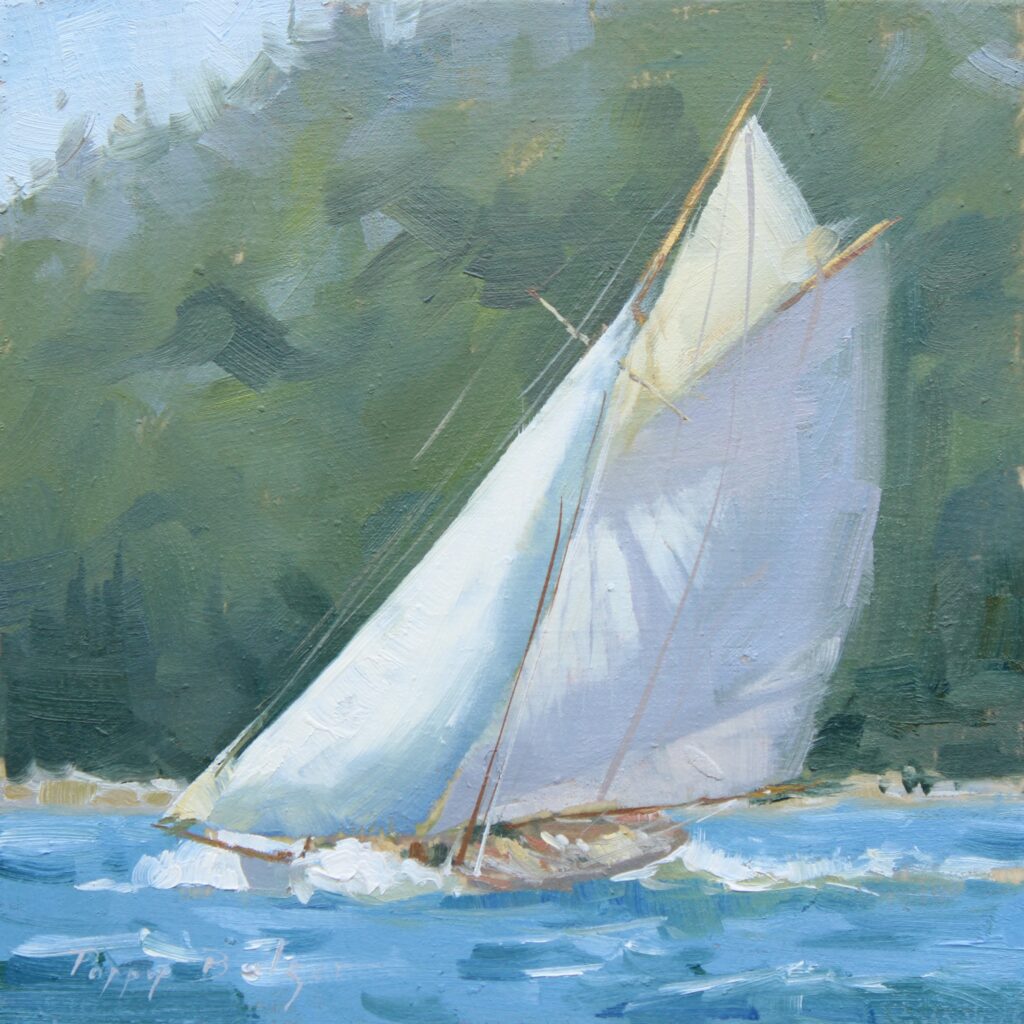

Here is one such little study that ended up leading me down a whole new path as far as portraying light.

I’d never painted anything quite like this before and so I started it as an experiment. I was pleased with it so I did several more small boats like this, immediately after, getting a feel for what did work and what did not.

From those smaller studies I went on to make a few larger ones, all pulling from the experiments begun in my initial studies.

This was a series of studio studies which led me to take this small painting practice outside. I find the small size much more manageable than a larger surface would be when painting at the seashore. For example, where I live, during mid-tide, the water level will rise or fall 5 or 6 feet over the course of an hour. As rocks are hidden or revealed by the waves the composition changes completely. This means I have to work quickly. I am still slower in oils than I am in watercolours, but I can more or less complete a 6″x6” study before before my scene is gone.

I used a palette knife in these, again, so I could work faster. I was painting outside and speed was of the essence.

When I came inside, I could slow down and paint with more intention, and a brush instead of a knife:

Perhaps you can see where some of the observations from my tiny plein air studies are incorporated in this studio painting.

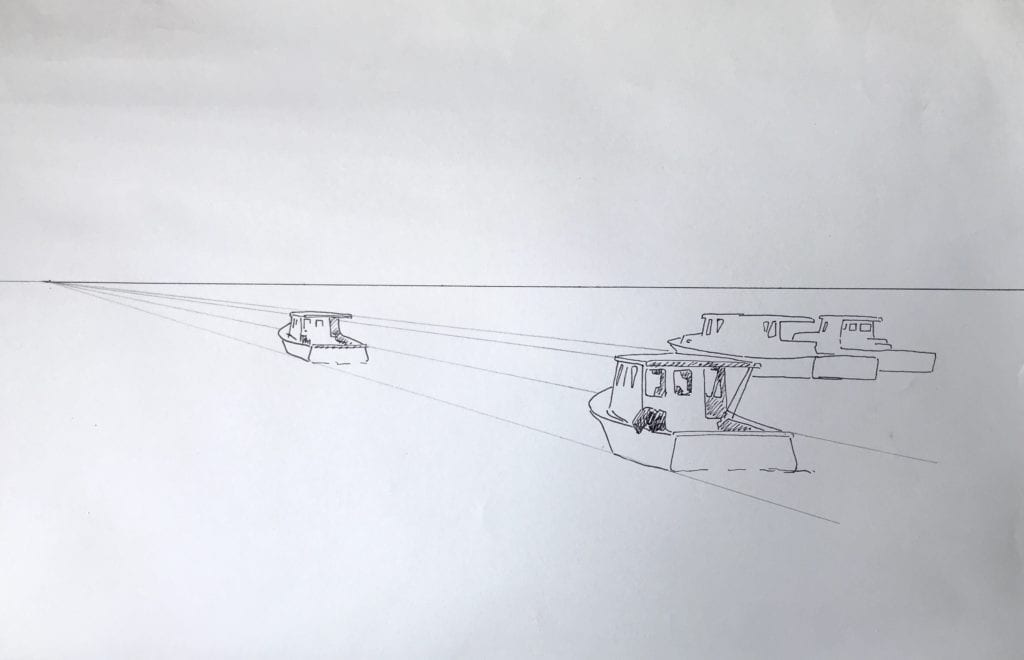

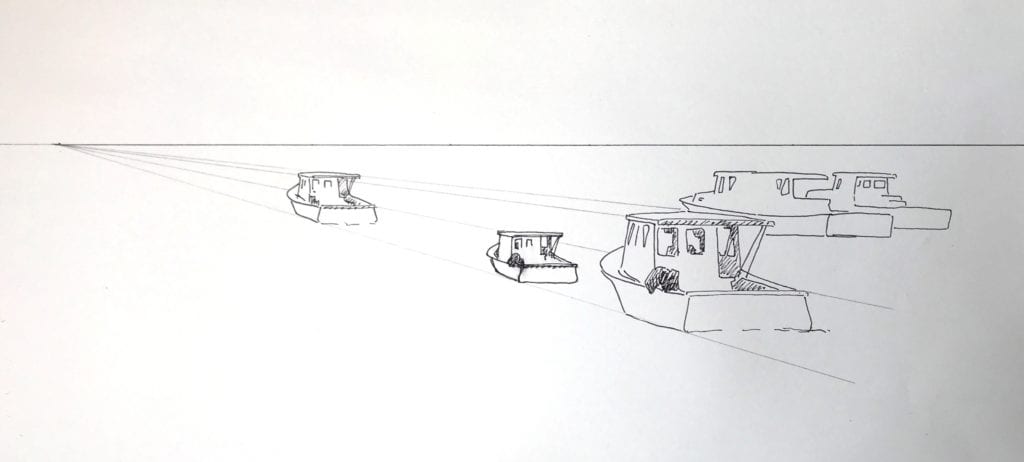

Lately I have come home from a trip where I was lucky enough to spend several days observing classic yachts in a regatta. I sketched on location (again watercolours, faster medium and easier to travel with). When I got home I wanted to paint all the boats. At once! There were so many boats I wanted to paint that I had a hard time choosing just one to start with. I started with a series of small studies so I could paint several of them, quickly, getting familiar with them and figuring out which ones I would want to paint on a larger scale.

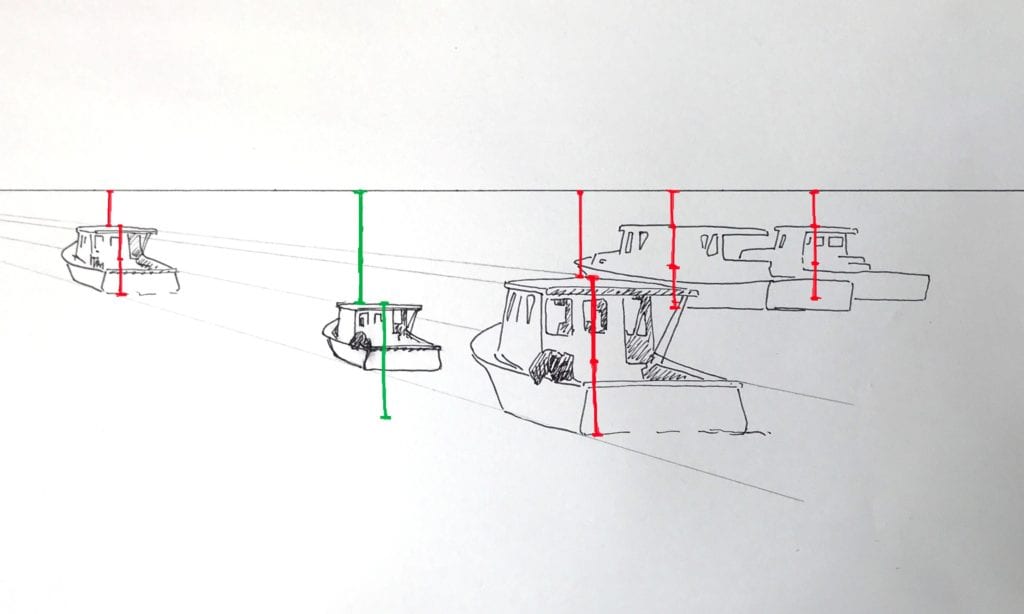

The lessons I am learning from these small paintings are important. Even now that I am a relatively newly elevated OPA Signature member, I feel like I still have much to learn about putting down paint. For one example, I have long struggled with backgrounds in my boat paintings. How much do I show? How much do I leave out? How much can I blur out?

If you look closely at the background in the two studies above you’ll see some progression between the first and the second. In the first I was still fixated on showing a discrete tree line whereas in the second I let go of that and discovered the painting doesn’t need it. I don’t know how many times I have read the words of better painters than I saying “simplify, soften edges, paint less not more”, but I had to have that happen in my painting in front of me to absorb what they were expressing.

To restate what I said earlier, it is far easier to experiment, and try risky ideas and be open to

accidental discoveries when producing many works on a smaller and less “precious” surface

than it is by working labouriously on one or two larger paintings.

I’ve taken the atmospheric blurry background from Classic Study II and put it into this painting:

I have left out the cluttered suburban background that was really there, letting me concentrate on the beauty of this elegant ship.

If you have read this hoping for a list of specific lessons I have learned over the years from my small studies, this is where I disappoint you. What I learned might not be the lessons that you will learn. The important message I want to share is: do the work. Experiment. Paint many paintings. Make them small for speed if you need that like I did. Try lots of different ideas. Make lots of paintings. Don’t treat each one like it is headed for a museum, or even a frame. Try something different. Mess up. Try again. Paint something else. Have some fun with the paint. The more you paint the more you will figure this thing out.

As for me, I will keep painting, on surfaces small and large, learning as I go.