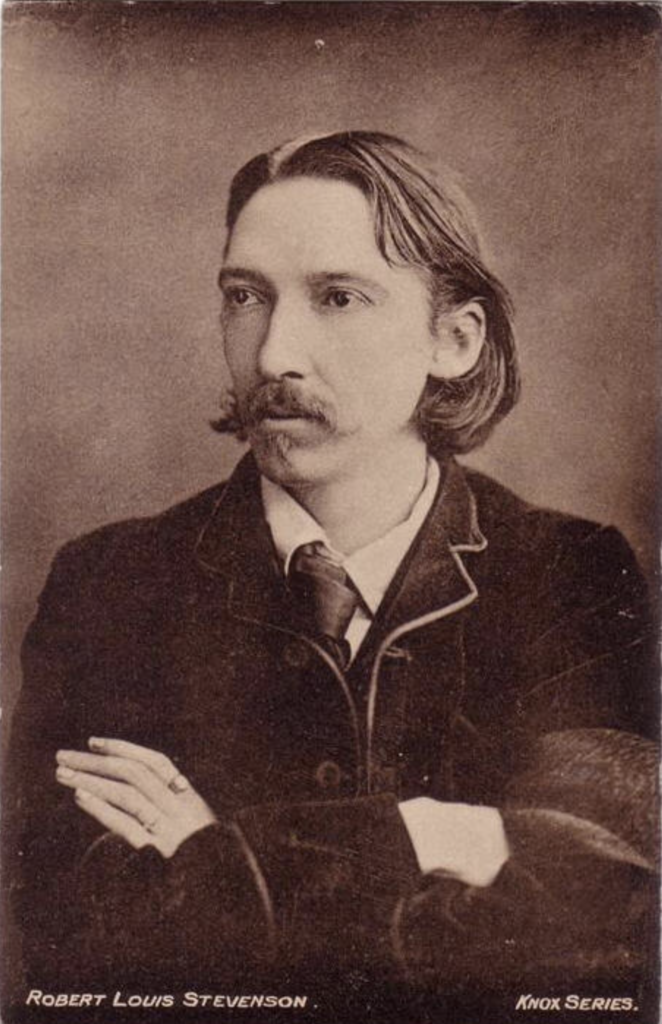

Some years ago, while raiding the family library, I came across a slim volume of essays by Robert Louis Stevenson. My grandmother had written her name inside the cover, along with the place where she was attending college: “Estella Rawleigh, Madison, Wisconsin”. Stevenson, of course, was the author of rip-roaring tales of adventure—Treasure Island, Kidnapped—but I was unfamiliar with his essays, and I made off with the book.

Well. Shiver me timbers—the essays are pure gold. One in particular I’d like you to notice. It has an awkward title, “Virginibus Puerisque,” meaning in Latin “for girls and boys,” but it’s a pure delight. It’s Stevenson’s take on men, women, and marriage, including his advice on what profession to look for in a spouse. Painters rate highly among the marriageable vocations, according to Stevenson (my emphasis in italics):

The practice of letters is miserably harassing to the mind; and after an hour or two’s work, all the more human portion of the author is extinct; he will bully, backbite, and speak daggers. Music, I hear, is not much better. But painting, on the contrary, is often highly sedative; because so much of the labour, after your picture is once begun, is almost entirely manual, and of that skilled sort of manual labour which offers a continual series of successes, and so tickles a man, through his vanity, into good humour. Alas! in letters there is nothing of this sort. You may write as beautiful a hand as you will, you have always something else to think of, and cannot pause to notice your loops and flourishes. . . . [But] a stupid artist, right or wrong, is almost equally certain he has found a right tone or a right colour, or made a dexterous stroke with his brush. And, again, painters may work out of doors; and the fresh air, the deliberate seasons, and the “tranquillising influence” of the green earth, counterbalance the fever of thought, and keep them cool, placable, and prosaic.

What do you think—is painting “highly sedative,” the sort of labor “which offers a continual series of successes, and so tickles a man, through his vanity, into good humour”? Does painting out of doors provide a “tranquillising influence”? For my part, the “continual series of successes” that Stevenson speaks of has eluded me for more than twenty years. There’s little that’s “sedative” or “tranquillising” about painting outside—it’s exciting—yes, certainly—and rewarding and addicting, but hardly sedative.

Stevenson wrote his essay a few years before John Sargent, a classmate of Stevenson’s cousin at the Atelier Carolus-Duran in Paris, painted the author and his wife Fannie in 1885:

Stevenson later described Sargent’s painting:

It is, I think, excellent, but is too eccentric to be exhibited. I am at one extreme corner: my wife in this wild dress, and looking like a ghost is at the extreme other end: between us an open door exhibits my palatial entrance hall and part of my respected staircase. All this is touched in lovely, with that witty touch of Sargent’s: but of course it looks damn queer as a whole.

In fact, there’s little about this painting that strikes me as sedative or tranquilizing. It’s dynamic and awkward and restless—and that’s what makes it great. I’d like to believe Stevenson would revise his opinion of painters after this experience.