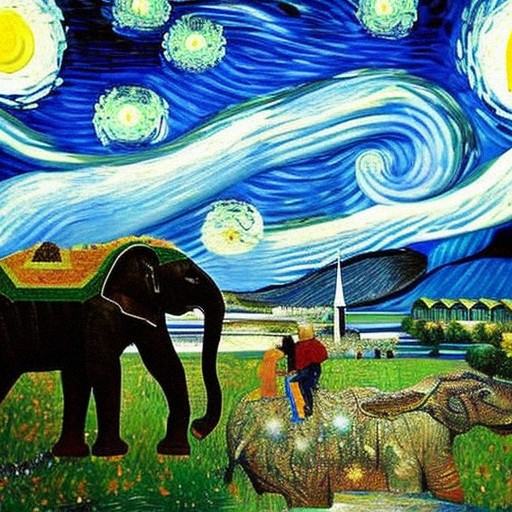

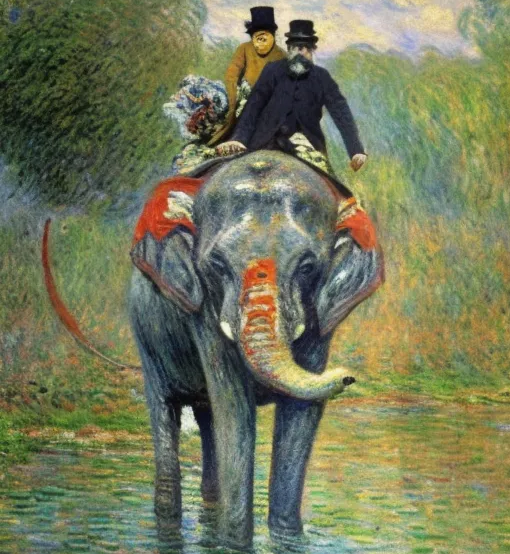

[Ed. note: Illustrations will consist of AI generated images of well-known historical painters riding an elephant in their painting style.]

Artificial Intelligence + Art.

Is it intelligent? Is it art?…

Cheap, fast, evocative imagery has been the goal of many painters for decades, if not centuries. But if you haven’t been paying attention to the recent advances in Artificial Intelligence (a term I will shorten to AI) and how it is being applied these days, I have some news for you.

AI image generators are now here and they are being used to produce artwork for little to no cost. While most of what you see today may seem amusing or weird you need to know technology of AI is still in its infancy. AI art will continue to quickly evolve and disrupt the world of fine art soon. It is already creating turmoil in the fields of photography, illustration, gaming, animation & film. So believe me when I tell you AI will start disrupting your world too.

But what is AI art? And why should you care? In simple terms, AI art is produced by entering text descriptor into an online AI engine and waiting for the engine to return a digital image assembled from similar images scraped on the internet. There is little to no skill required, just a brief description of what you want combined with a seed image to style the result.

All the illustrations included in this article have been generated by me using three AI engines with a similar prompt: “[Name of famous painter] Riding an Elephant”. Each engine appears to have its own quirks and specialties.

So if you are a professional artist, or have aspirations to become one, there are several things you want to monitor: specifically, how fast AI technology is advancing. The glitches and oddities we see today will be gone within 6 to 12 months, making it difficult for everyone to differentiate between a photo of painting and an AI generated image pretending to be a painting.

AI can produce an image that may appear at first glance incredibly realistic. That is until you look more closely at the image and realize it is a digital pastiche gone horribly wrong. Hands with six to twelve fingers, heads with mis-aligned eye sockets, odd-looking pupils, too many arms & legs sprouting out of a torso or head. (For examples, see some of the elephants in this article.) The realistic veneer AI can produce feels simultaneously authentic and creepy – a perfect example of what the animation industry has long called falling into the Uncanny Valley – a phrase coined to express what was once considered a paradox: the closer a computer gets to replicating reality, the more humans are creeped out by the remaining gap between CGI and reality. But the Uncanny Valley shrinks everytime CGI software is updated and eventually that gap will close completely and you will never know if an image is real or not.

So now you know what AI art is. But more important, how will it impact you and your art? Unless you make your living producing surreal or fantasy art, probably not much yet.

Yet. – I predict AI technology will fundamentally change how the world views and values art. Why? Because soon there will be so much AI art produced that the sheer volume of it will alter our cultural tastes and unless new laws are drafted and implemented quickly the technology will run rough-shod over existing copyright law and change our idea of what it means to control our own work.

I have a close friend who is a well-known, painterly illustrator. He is litigant in a class-action lawsuit with three AI engines that have scraped his work more than 200,000 times. His work was not only scraped for his imagery and style, his name has been illegally attached to some of the AI output, which is what his lawsuit is about. (An image, AI or not, is not considered a forgery until someone attributes it to an artist who did not produce it.) The fact that my friend is so well-known and popular, and works at such a high level in the industry, makes his work a prime target for AI engines.

The definition of art forgery can be reduced to this: You and I have the right to copy an artist’s style and content as much as we wish, be they well-known or not, but the moment you or I assert the work we’ve created was produced by the artist we copied we are committing fraud. Fraud does not occur when someone makes an image. It occurs when they lie about who made the image.

In rough numbers, 3 to 5 billion images are uploaded to the internet every day and that number will keep rising. If you don’t believe this factoid, google it. This means at the top end 57,246 images are uploaded every second! All the paintings you and I have posted online are now being scraped by AI bots seeking to appropriate them for someone else’s purpose and profit – and therein lies the problem.

Under the revised 1977 US Copyright Laws, as soon as the work is completed, a copyright is created and owned by the creator. No other action is required to generate a copyright.

However, if AI bots are able to scrape every image online and reassemble bits and pieces of them all into a “new” image for someone else’s benefit, you won’t know when, how, or where your work was scraped. Or how it is being used. (My friend was able to determine the extent to which he had been scraped by checking with www.HaveIBeenScraped.com – a site that is no longer online.)

So the AI legal questions become: Can a bot be creative? Can it produce an “original” work of art by combining images from other artists’ oeuvre? Is creativity an act limited to humans or can a bot produce an original as well? And when it becomes impossible to differentiate between images produced by a human and a bot (which will happen soon) will such distinctions matter? Remember, AI can appropriate your time, effort, expertise, and yes, even years of sacrifice without offering you compensation.

I am not talking about the future. The future is now.

Like many painters today, I started out as a designer, art director, & illustrator. I spent 30 years in the biz, both as an employee and later as the principal of my own firm. I was good at what I did and enjoyed every minute. I made good money until I decide to shut it all down and become an artist. (Which is story for another time.)

During the same period, I invested a lot of time and resources into learning how to paint at a professional level. I produced work to sell in galleries and exhibit in museums and built up a personal collector base. Not an easy thing to do when you are holding down a 60 hr/wk job or running a design practice. And if that wasn’t enough, I also chaired a four-year BFA program for ten years where I was responsible for developing curriculum, hiring and firing, maintaining national accreditation, and yes, teaching undergrads on a daily basis throughout the week.

AI can do most, if not all of these tasks now. Or it will be able to soon. Both in the commercial and academic sectors.

I have always visualized mass culture as a gigantic amorphous swamp in which competing trends and topics burp and bubble their way to the surface, often without logic or apparent cause and effect. But now, due to the massive amount of information collected from you and I as we consume everything from food to media – the Big Info/Service/Entertainment Complex has become a cultural behemoth loosely synchronized by the sale and exchange of our information. For example, consider how pop music and block-buster movies are engineered today: Not written. Not filmed. Not scripted or directed via artistic intuition. Instead, engineered, verified, and market-tested before being released to the public. These industries use your data to anticipate or shape social trends in the hope that such granular knowledge of you and I will guarantee a return on their money. AI will be applied to every artistic discipline because it reduces corporate risk. In effect, AI will homogenize the content you and I experience.

Here is another prediction from me. (aka Mr. Plein Air Nostradamus). AI will pervade our society to the point that high-end art collectors will start seeking out what they believe is the authentic; meaning, what verifiably comes from a human. Art that expresses the human voice and condition. And if that voice resonates with them, those collectors will be happy to pay a premium for it.

If you have read this far then you are probably a painter. If you aspire to make a living from your work then focus on putting your own voice in your work – not in the giclee prints you produce, or the merchandise you hope to license. Put your voice into your originals because that will be what will makes your work meaningful to others. If you produce only originals, one-offs, then the demand for your voice will become stronger, because if there is only one of something, it is the original, and collectors like originals.

So with regards to AI, what can you do? Think about what makes your voice resonate. It may feel narcissistic to frame your motivation this way, but what you and I do is inherently narcissistic so cop to this fact and move on. After all, we artist must become a little self-focused if we are to survive the oncoming uncertainties of our chosen calling.

In the end you and I will not be able control how AI bots impact our community because there is too much money at stake. And to be fair, there is an upside to AI. It will increase efficiencies in critical service sectors such as healthcare, investment, manufacturing, travel, energy production, conservation, and more. So AI will have a positive impact on most people.

But by all means future-proof yourself by pouring your singular voice into your work. To steal a quote: “Now get out there and go do the voodoo you do so well.”* Focus on your own creativity but keep strengthening authentic relationships with your friends, peers, and collectors because they will be the people who continue to value what you do.

–––––––

* If you are of a certain age like me, you might think this quote comes from Mel Brook’s “Blazing Saddles’ but it does not. It was coined by Cole Porter in a 1929 song and later appropriated by Harvey Korman for the 1974 movie – a perfect example of the burp and bubble of our cultural swamp.