“When I reacquainted myself to oil painting in the late 90’s, I’d already been a professional musician (ok drummer) and actor for most of my adult life. I was a realtor too at the time so combining that with all my other “art idiocy” as I affectionately called it, when someone would ask me what I did for a living I’d say with confidence “Rejection is my business! Ha!” After selling some pictures and getting a toe hold in galleries and juried shows, I could now say I was a professional oil painter! Having long vacated the real estate world, when the prior question is now asked, I just say “I revel in discomfort and uncertainty!” A little self-indulgent but all this “professional” art stuff has become a lifelong journey and the nagging feeling of insecurity is a constant and necessary companion. Here are a few stories of friends I admire deeply to help illustrate.

Long ago in my mid-twenties, I worked in the drum department of an iconic music store in Hollywood, California. At the time there was also a 19 year old kid I was working with who since then has gone on to amass a resume as a session/recording/studio and touring drummer that is second to none. I recently caught up with him playing on a sold-out stadium concert tour in one of the most legendary rock bands of all time. In one of our conversations though, he was quite adamant that through the professional ups and downs, he’s routinely found himself at odds with his true ability and skill. But wait! He’s always learning, growing, practicing and applying his craft at an extremely high level. Certainly, after all these years with incredible credentials, he can now just relax, be comfortable and ride it out! Right? Nope! I think for him, with each level of advancement, there’s an awareness of what might never be. The ascendent journey never has an end and that can lead interestingly to a healthy sense of insecurity of being able to deliver in any musical situation he volunteers to put himself in. I don’t mean to say that he’s ever timid or unconfident- that wouldn’t be true at all, but a little discomfort is a sure sign of being on the right track! He’s proof positive!

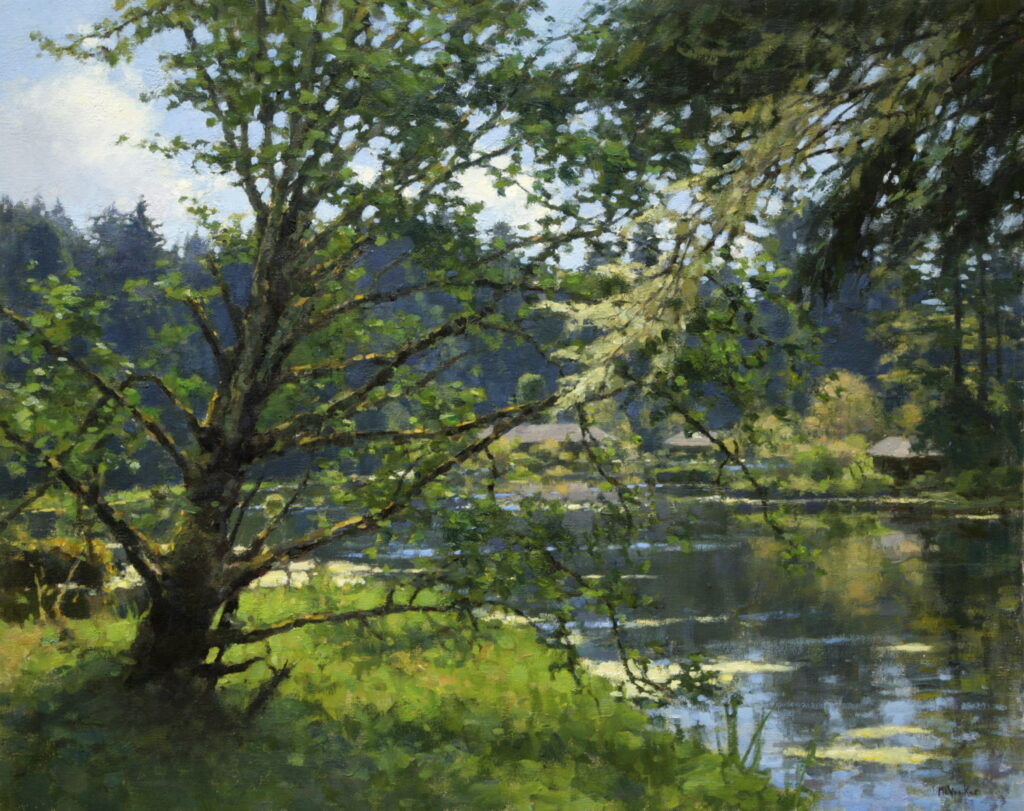

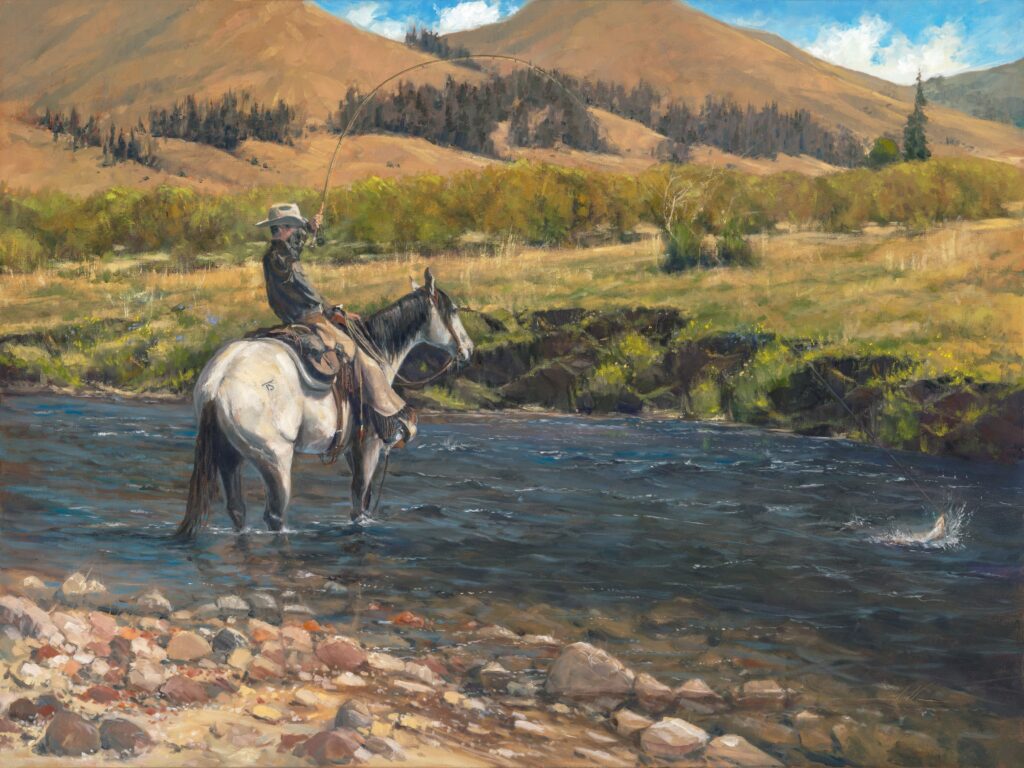

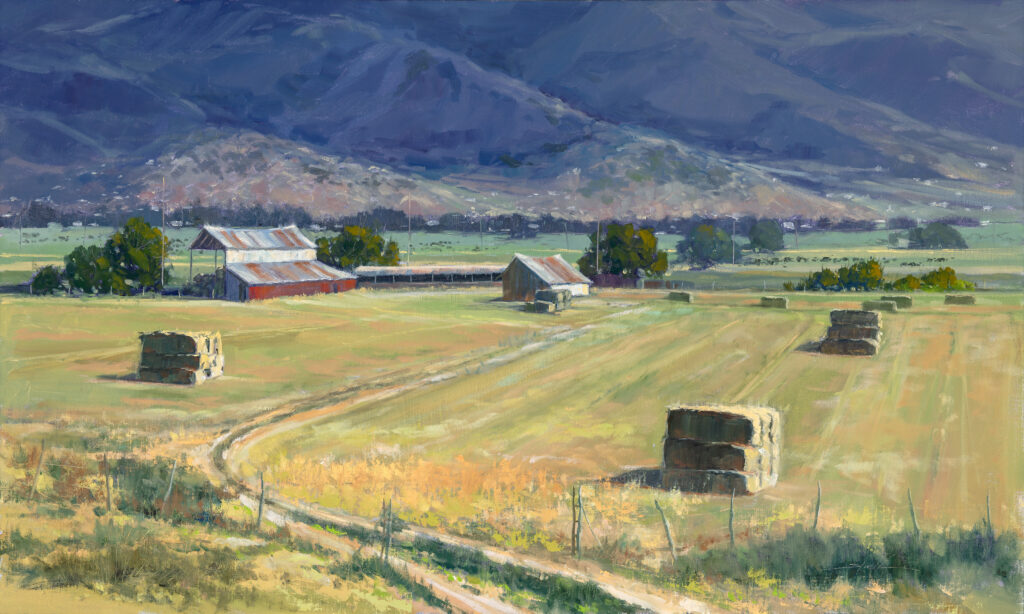

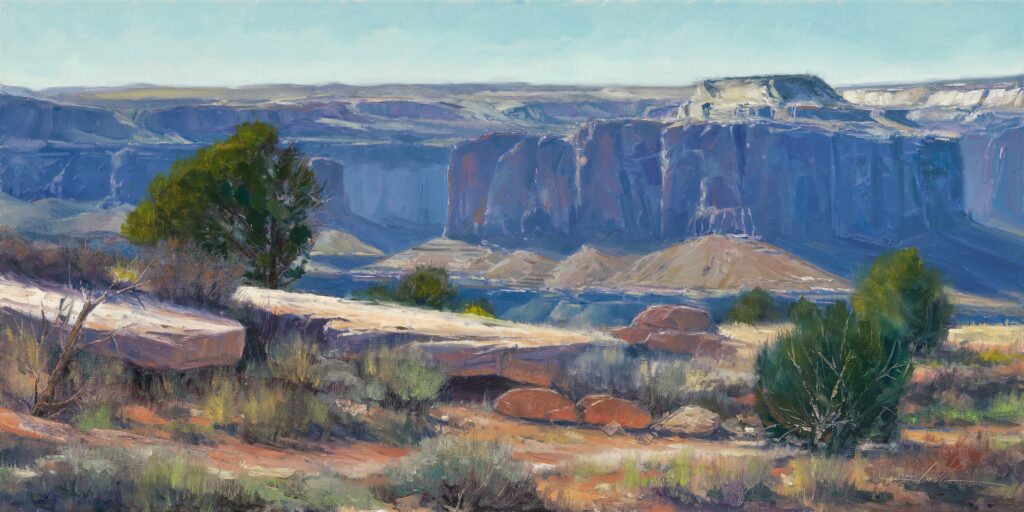

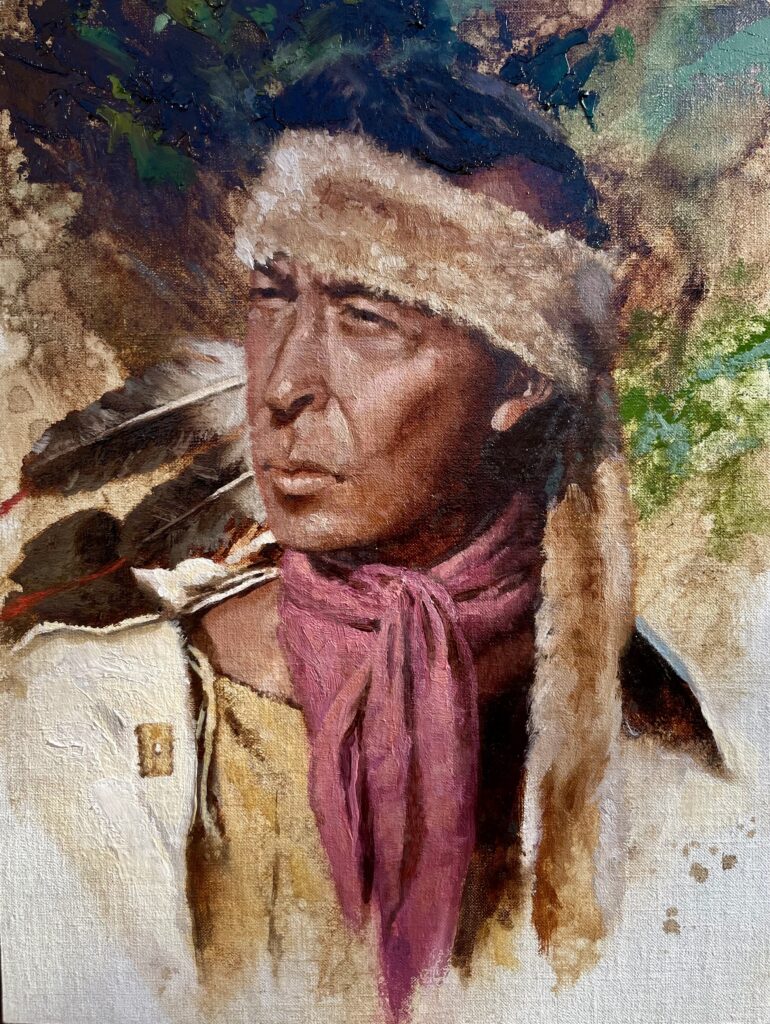

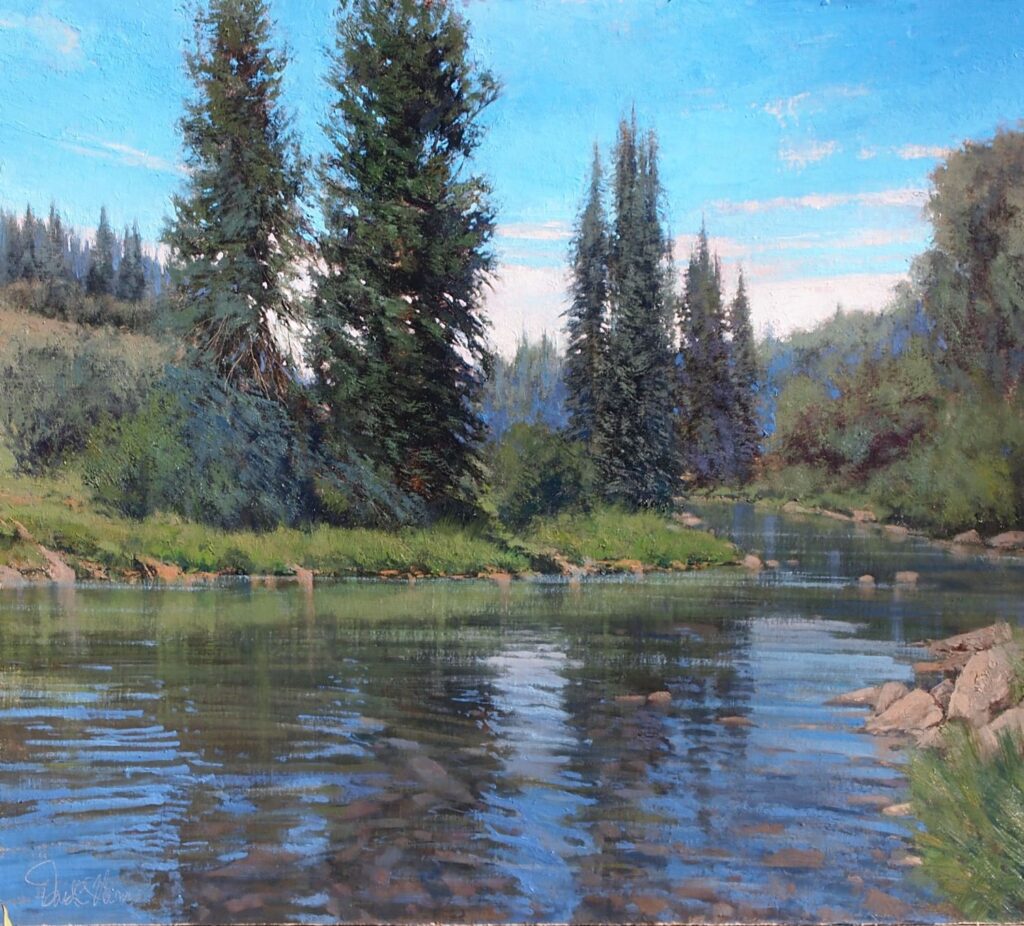

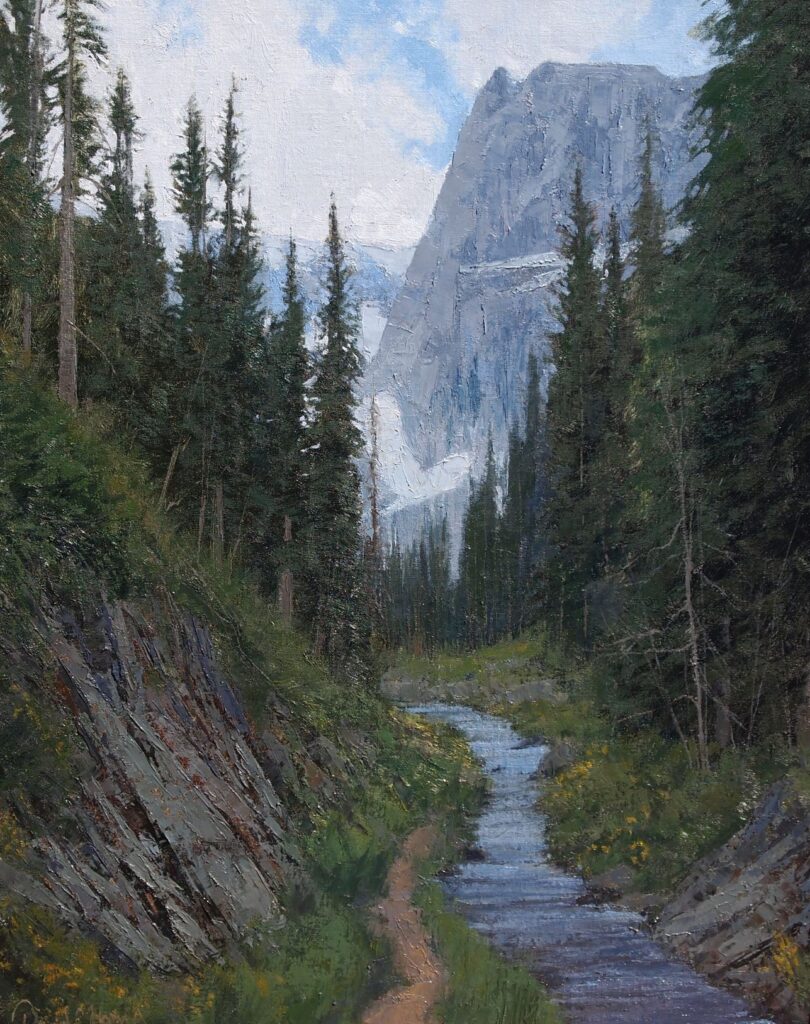

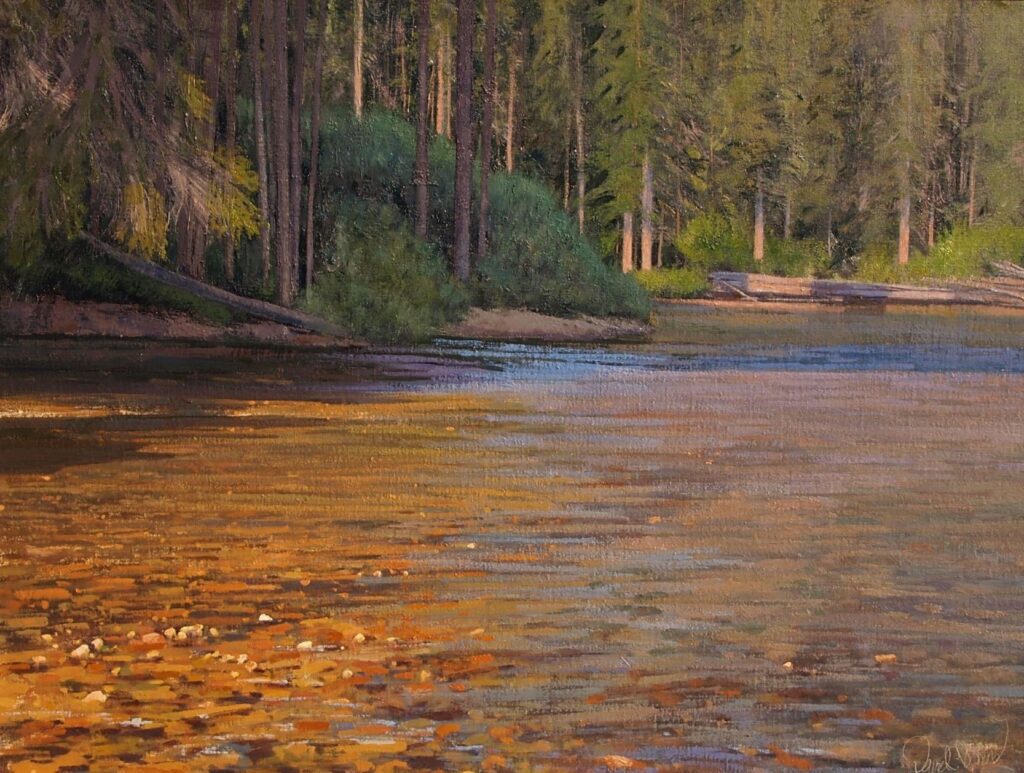

I recently had the absolute great fortune of being able to spend an afternoon in the studio with one of my most favorite western/landscape painters of all time. For the first time being in the very workspace full of incredible paintings with the very artist who created this entire oil painting wonderland was a revelation! And there he is, “the man” just basking in the glow of achievement and prestige! Right? Nope! As I’m exploring the room marveling at all the studies/paintings/books and everything else that exudes a comfortable professionalism, I look across only to see him sitting with his head in his hand looking unsatisfactorily at a small (11×14 maybe) painting secure on his massive easel. Let me guess, he just knocked out this little gem as a study for a larger piece. Easy! Not so fast! “I’ve repainted this thing for 3 days and it’s killing me”! Uh, say what?? Further discussion revealed that for him, painting just keeps getting harder and harder. Doubts and insecurities for a guy like this- one so accomplished and revered? I’m starting to see a trend here.

I was recently invited by OPA to participate in their longtime critique program, matching a Signature member with someone of similar style. The idea is, for fortunate souls like me, to give aid and criticism/critique to a fellow member on their paintings and anything else helpful. In this case it was specifically “Why aren’t I getting juried into any of our shows? What am I not doing?” Oh my, the eternal dilemma. Hmmm can I possibly deliver the magic formula? Nope! I truly looked over and commented on a marvelous collection of paintings by a very talented individual. In one instance, trying to be of possible compositional assistance regarding a cluster of bushes on a particular piece, I was told that this painting had actually made it into a prior exhibition. So much for my insight- Go figure! To be clear regarding getting critiqued and OPA’s program, we all need the right eyes with experience to help sharpen our focus and approach and set a platform to launch our own development. But what I soon realized, in essence, was the question in so many words- could I possibly, maybe, perhaps help in overcoming any future insecurity/doubt when entering future shows? Hopefully not! Here’s why-

As a dear departed friend and longtime fellow professional actor used to regularly say to me to keep in mind before any of my stage performances was “If you’re ever comfortable, GET OUT!!”. What I think this speaks to is the notion that discomfort, and insecurity are necessary ingredients for any worthwhile professional endeavor. Why? Because you can’t ignore the task at hand and being alert and focused are paramount. You can’t help but experience depth and growth. Look, we’re all on a thrilling journey of constant discovery and doubt because it simply has no end and the only thing I know for sure is that I’m not good enough!! If I project myself way down the road I still know I’m not good enough.. and still not…! Oh yeah, an awareness of what might never be! I don’t care about that anymore because this discomfort and insecurity only scream that I’m on the right track! Perfect. That’s all I really want. You already know you’re an artist so get to it! Does this always lead to success or reward like sales and juried shows? How do I know- how does anybody know? It’s like parenting- nobody has a clue but it’s relentless. Be relentless! And lastly, referencing back to my music store days-

After I asked what I thought, were vital probing questions about the behind the scene band stuff and keys to success in music, Alex Van Halen simply said to me ‘I don’t know Dave, I just show up”! Have fun staring down that big (or small) sheet of white canvas and the unknown. Show up and be secure in the insecurity!”