When I first considered making a contribution to the blog, it was with the thought of talking about the amazing and exceptional way Richeson manufactures our Oil Paint. I say that a bit tongue in cheek, because as a salesperson I know virtually every manufacturer will say the same. From my comfortable perch on this train I feel far more inclined to delay what I truly believe is a justifiable “sell job” for a future blog. Instead I would prefer to share with you a secret about the many many manufacturers and retailers that make or sell the many ranges of Mediums you use in the pursuit of your passion.

You see……many are artists in their own right who have ventured into the strange land of making or selling art materials out of a desire to stay close to the artist community as they earn a living and yet while under cover of darkness they pursue their art after working hours. I also know many folks involved in manufacturing who got their start as frustrated artists desperate to improve the quality of a medium but were frustrated with the materials available to them.

There is however a dark side to the secret I share with you. An ugliness has been creeping into the passionate Retailer and Manufacturer’s pursuit to serve the Artist Community. The never ending push to drive down the cost of artist materials over the recent years is at risk of seriously impacting quality. You may well ask……Is competitive price reduction such a bad thing? After all…..I confess…..I too must shop for the best value I can afford.

So where is all this rambling on a long train ride from London to Edinburgh heading? It leads me first to reflect on my own guilt at too often purchasing solely on price and neglecting quality, only to later grumble and moan because the silly thing has not functioned or lasted as I expected. I chide myself and renew a commitment to purchase the finest quality widget or thing I can possibly afford for the money available to me.

Enough rambling from my seat on a train in the British Countryside. Next time I will expound on our passion at Richeson for producing only the finest Oils available at a price that is affordable without the need to take out a second mortgage!!!!

Colors

Marc Hanson Interview

“Painting from life, plein air if outside, is critical and necessary to me for what I want out of myself and out of my Art”.

Besides the airplane, he’s also building a boat…a 12′ flat bottom rowing skiff…and it’s all done except for sanding and painting. Add to that his landscape painting and I think he’s pretty much got it all covered…land, sea, and air.

When you talk about Marc Hanson though, you’re really talking about a man who is absolutely dedicated to the craft of painting. He is most at home outdoors in the open air, brush in hand, capturing on canvas his excitement about the natural world. He feels most confident expressing himself in this way, visually, through painting and drawing as opposed to writing and speaking. That’s probably not uncommon for us visual artists, but believe me, Hanson is no slouch when it comes to writing. As you will see in this interview, his answers are seriously considered and clearly stated.

Marc’s primarily a plein air painter and he’s out there rain or shine every season of the year. He works mostly in oil, but also in pastel…and sometimes even in qouache. Because of the hundreds of paintings he’s done on-site, there is an absolute authentic reality associated with his work whether the paintings were conceived in the studio or outside.

I had the pleasure of meeting him at a plein air event we both participated in last year in Kansas. Organized by Kim Casebeer, a group of us spent several days painting in the Flint Hills and Steve Doherty, editor of Plein Air magazine, reported on the event in the Feb/Mar 2012 issue.

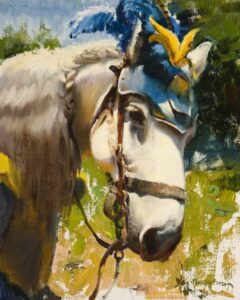

It was a challenge selecting images for this blog. It’s like being forced to choose just one M&M candy from a large bag of many colorful, delectable possibilities. They all taste the same, but oh, so many choices…which one to choose? I wanted to take them all, but…

That’s a big question, one that much deeper thinkers than me have pondered and explored. But…my take is that Art is the expression humans use that incorporates a skill other than communicative speech, to show others what they feel about the world around them. Music, Dance, Visual Art, Poetry, Prose…these are all ways that we humans use to talk about the world around us, in an intelligent way, based on our emotional reaction to our world, that is unique to our species. Other creatures build amazing structures, have incredibly beautiful song and sound, and they communicate with their own kind. But we are the only species that can ‘create’ beauty, ART, as an expression of our emotional existence.

How do you define your role as an artist?

My role as an artist is to be honest with myself, so that I make Art that is solely mine. I have no illusions that what I do does or will matter to anyone other than me in the end. Not to slight those who collect it, and compliment me on it, that’s an honor that I never discount. When Art is your life, however, you live it, breath it, are up and down with it. If I stay true to myself and honestly evaluate what and how I’m creating it, then all of the other factors will fall into the place that they belong, whatever that may be.

How does one find their individuality as an artist?

Paint, paint, paint! That sounds simple, but it’s the key. Once one has the skills in hand to be able to self evaluate, with occasional help from your peers, diving deep into your own creative space and working hard is the best way to see who you are as an Artist. Style, or individuality, will come out of you, it can’t be held back, if you’re really working hard at your art.

Your paintings are uniquely yours because of the many paintings you have done. I suppose your personality is reflected in your work?

I’m all over my work. My background as having always been interested in bugs, birds, things that bite and slither, large furry things, and where they live, has made me pretty sensitive to Nature and her color and mood. I’m fine being with myself, with being in a quiet place and state, and my work reflects that I think. I’m pretty happy about life. I don’t paint dark and tragic, unless I’m painting a severe thunder cloud…and that’s fun to me.

Plein air painting is pretty important to you, just how important is it?

Painting from life, plein air if outside, is critical and necessary to me for what I want out of myself and out of my Art. Life is where the truth lies, the truth in color, in spacial relationships, in texture, in shape and all other visual aspects of the subject. Photographs are a hollow substitute, one that I am always hesitant to use, but do. Painting from life is a joy, painting from photographs is pure drudgery in my opinion.

What is the major thing you look for when selecting a subject?

I look for something that makes my ‘painting eye’ light up and begin seeing the possibility for a painting in it. I’m not looking for a thing, I’m looking for a combination of the elements that make a painting, first the light followed by how that is affecting the color, edges and design. What is the impact on me and what is it that caused me to be interested in painting the subject in the first place.

Do you consider the process of painting more important than the result?

No…Every part of painting, starting with what I feel is most critical…the Concept…is important to the Art. The Result is the product of all parts of the process, the Concept, and the implementation of ones techniques and skills. The quality of the Result is tied to the level of skill and maturity of the artist, meaning that they are both as important in the end.

You speak of the importance of having a concept in mind before painting. Do you let the subject determine that concept or do you create the concept and use the subject only as the starting point?

The subject is raw material for a concept. Concept is #1numero uno to me. A concept has to at least be thought of before any other element or design principle can have a purpose in a painting. If you don’t know what you are going to do, what your concept for the painting is, how do you use those elements? I’ve painted paintings to music, emptied my head, had no concept whatsoever other than to listen to the music and apply paint according to how I felt about it…almost concept free painting. I see many students, who until I harp on it, have no concept when they begin…and they usually flounder until they decide ‘why’ they’re painting the painting. That does not mean that a concept locks you into anything, it only means that you have a reason to proceed.

How do you decide on a dominating color key for a painting, and how do you maintain it?

I let the color harmony of the scene determine that for me. I will squint, turn my head nearly upside down or sideways to try to get a sense of what the color of the light is in the scene. Then I am very careful to pay close attention to my color mixtures so that they are in that harmony as I put them up. I test each color on the painting each time, several times, before I commit to it. Another reason for painting from life, the color harmony or ‘key’ is already there. The problem is how not to destroy that if it’s what you want in the painting.

What is your major consideration when composing a painting?

I look for a way to set the stage so that I can talk about what it is I have to say. It’s about that simple to say, though complicated to implement.

How thorough is your initial drawing?

That depends on the complexity of the situation. But I’m more of a ‘large shape’ kind of painter now. I get the big proportions going, simple shapes as possible, and then refine down to the details from there. So, a complex drawing would be counterproductive. That’s the way I paint today. I came out of the ‘tracing paper overlay’ world as a younger artist/illustrator…and am happy to let that go.

What colors are most often found on your palette?

Titanium white, Naples yellow (light version), Cadmium lemon yellow, Cadmium yellow deep, Yellow ochre (lighter version), Cadmium red light, an Earth red (Venetian, Terra Rosa, English red light, etc), Alizarin crimson, Transparent oxide red, Viridian, Cobalt blue, Ultramarine blue deep, and often now a blue like Manganese blue…and sometimes Chromatic black.

Describe your typical block-in technique.

One way is that I get a cheap 1-1/2″ or 2″ bristle varnishing brush (hardware store variety $1.79) and start knocking in big blocks of color pretty fast. Usually using a colored block-in that gives me an idea of what the large masses of color will look like in the composition. Then I lightly wipe out most of that and begin to restate the drawing or just begin applying areas of color.

Do you paint in layers?

In the studio, yes I do. And on multi-session plein air landscapes I also do.

What are the key points one needs to know when creating a true sense of atmosphere?

I might just answer that by saying that if you just pay attention to the relative color and value relationships, you’ll be fine. However, having just taught a class, I know that’s my experience talking. Studying recessive situations from life, understanding recessive color theory, then going out and trying to make your color recede and reflect the atmosphere that you’re painting is a way to improve that in your work. Every situation is different outside. Unless an artist wants to paint a generic reflection of the landscape, studying and painting from life is the only good way to create the atmosphere that you’re seeing.

How much of your work is intellectual vs. emotional…and how would you define the difference?

I would say that it takes the intellectual to produce the emotional. The process is intellectual, although as time goes on, some of painting is almost intuitive…things like mixing and applying paint (that comes up as I’ve just come off of teaching a workshop. It’s not automatic to students, still in the low end of the learning curve, how to physically make a painting…things like how to mix and apply paint is a big deal to them). The quality of the end result has to be full of the emotional or it will be but a rendering of a ‘thing’. When the masters reach that place where the two mesh…the intellectual and emotional are working in harmony…they produce poetry…Art.

What part does photography play in your work?

It plays a big part when I’m in the studio, along with field studies. Especially if I’m needing to paint Cape Cod when I’m in my Minnesota studio. One reason I just relocated to Colorado is to be able to be outside painting more often and not stuck in the studio so much. I always try to only paint an area that I have first painted from life, or at least where I’ve done some work from life to be able to know how the light in that area looks. If I need to pull out the photos on the computer, I use the photo as a starting point and let the painting emerge and grow into it’s own thing, away from the photo usually. At that point, I barely look at the computer.

What are the major problems encountered when translating a field study to a large studio painting?

I would say that if you expect to recreate the field study, you’re bucking up against a big wave. I realized that the field study is there as a starting point into a different voyage, to give you some notes that you can use to create a brand new image with it’s own inherent qualities that were not in the field study. Trying to replicate the 4″ swish of an emotional brushstroke at a scale that is 3 or 4 times larger in all dimensions…is nearly impossible. The field study is a ‘note’, maybe a pretty finished one able to stand on it’s own, but as far as a larger studio painting goes, it’s just a reminder for me.

I notice you work in both oil and pastel, why do you do that, and what are the significant differences?

I started pastels many years ago because I had a show coming up and needed more work, faster. I took to it immediately. They have the sensitivity for me that is attractive for rendering natures’ textures. I like the broken color that is achievable with pastel, and it’s taught me a bunch about color and using color in the oil paintings that I wouldn’t have thought to mix on my own. Otherwise I paint with pastels in the same basic way that I paint with oils…dark to light, thin to thick. I break the pastels into brushstroke sizes and use it as sweeping strokes. I don’t draw linear strokes with it. I think it’s always good to switch mediums from time to time. I also use gouache for field studies pretty often. That’s my third favorite medium.

What advice would you have for a young artist/painter?

I like what Henri said…to the effect…paraphrasing…’Discourage and dissuade any child who wants to become a painter and if they still want to, then they may have the fortitude to withstand it all, and succeed’. Wish I had the quote at hand on that one, but that’s basically the idea. I’d tell them that they need to seek out good advice and training, learn to draw first and foremost. I’d also tell them to try every medium, technique and style that they can. Learn about all of the materials and techniques that they can. Too many painters I run into today start with a workshop, learn about one kind of brush, one palette, one kind of canvas board. Materials are like musical instruments or dance shoes…every artist finds the ones that work best for them. If all they use is the ‘one’ that their first instructor told them to use, they may be missing out on the ones that take them to a higher level of creating art. Young artists are in a great place right now. There are academies, ateliers, workshops and schools all over the country from which to pick either a designed curriculum program, or in an a la carte way.

What advice would you have for a first-time collector?

I would have to say that is really dependent on the level of the spending the collector can do. If it’s a few hundred dollars, local galleries and art shows would be a way to begin to follow the artists and art that appeals to them. Also, educate themselves by looking at magazines like American Art Collector, American Art Review, Southwest Art, etc. I’m sure that gallery owners would be the best ones to answer this question, so I’ll leave it at that.

If you could spend the day with any three artists, past or present, which would they be?

Sorolla, Levitan and Monet.

Who has had the most influence on your career, and why?

My Dad. He was a part-time artist and always my biggest supporter and encourager to become an artist or anything for that matter. He shared all of his knowledge with me about art materials, from crowquill pens and India ink, to woodcuts, oil pastels and oil paints. He even did scrimshaw later on in his life. I would not be doing this today if it were not for the hours of his life he gave me.

How important are art competitions and how do you decide which piece to enter?

I like to enter some, OPA is my main competition. I use it as a yearly barometer for my progress. Nothing like seeing your work amidst the work of your peers, year in and year out, to see how you’re doing. It’s an awakener.

Thanks Marc for a great interview and your willingness to share your thoughts with our readers.

- Marc Hanson website

- Blog

- Addison Art Gallery

- American Legacy Gallery

- Elizabeth Pollie Fine Art

- Ponderosa Art Gallery

- R.S. Hanna Gallery

Click here to receive John Pototschnik’s monthly newsletter

The Spirit Forges Ahead While the Brain Has To Figure It Out

1.) An answer for countless viewers who have remarked that I certainly painted a lot of different subjects. Now I had a way to tie many of them together.

2.) A better understanding of my artistic hard-wiring, which

a.) I can use on occasion to find what I want to paint faster and more easily

b.) In a purely narcissistic way—a fascinating (to me) fact about myself, of which, after all these decades I had been unaware.

Every piece I do does not feature white on a color field, but now when it happens, I smile to myself and recognize it as another chapter in my love affair with this combination.

If you feel there may be a hidden theme in your work, or some unrecognized essence, or you wonder how all your painting threads connect, I have a suggestion: block out some time for a lunch with a savvy artist friend and leisurely peruse each other’s portfolios. A fresh eye and a frank discussion may uncover a powerful current flowing just under the surface of your paintings.

Uber Umbers and Other Colors from the Earth

People perhaps just hacked a chunk off the cave wall and started noodling, or charred a bone from last night’s dinner, or took a stick from the fire and began to make marks. The earth itself for thousands of centuries has created a harmonious palette of archival and readily available colors to create some of the most beautiful and enduring art in the world.

This topic has become a passion for me over the recent years, and I have experimented with most of the available historical pigments in one way or another, creating several in-depth projects that involve both artistic and cultural research. The most profound characteristics discovered are that these pigments are splendid to work with and endlessly beautiful.

To my eye, the modern cadmiums are so highly saturated they overpower my canvas and are difficult to handle on the palette. I find this true also of other modern colors such as phthalo greens and blues. Occasionally, when my mad-scientist self gets restless, I break out of this mold and experiment with some of the modern azo, turquoise, and quinacridones, but I usually will spend time muting or graying them down in some way.

It really is a process of elimination. I use just the colors that are safe after they are encased in oil and toss out the fugitive (many of the plant-based colors) or toxic colors. I use caution and strict hygiene habits while painting. Most importantly, the mere fact of having a few select colors on my palette to deal with allows easy and quick decision color mixtures.

More and more interest in hand-ground paints made from natural pigments is surfacing lately. I invite you to choose a few colors, (even if you do not grind the paint yourself, purchase the ready-made), and experiment. Do some studies and see the difference in the surface quality of your canvas. Make that connection between you the painter, the aesthetic of your art, and your materials. The results just might be profoundly gratifying.