I had the privilege of meeting Suzie Baker, briefly, at the Oil Painters of America (OPA) National Convention, held in Dallas, a few years ago. However, the first time I became acquainted with her work was when she won the Artist’s Choice Award during the 2014 Outdoor Painters Society “Plein Air Southwest Salon”, of which we are members.

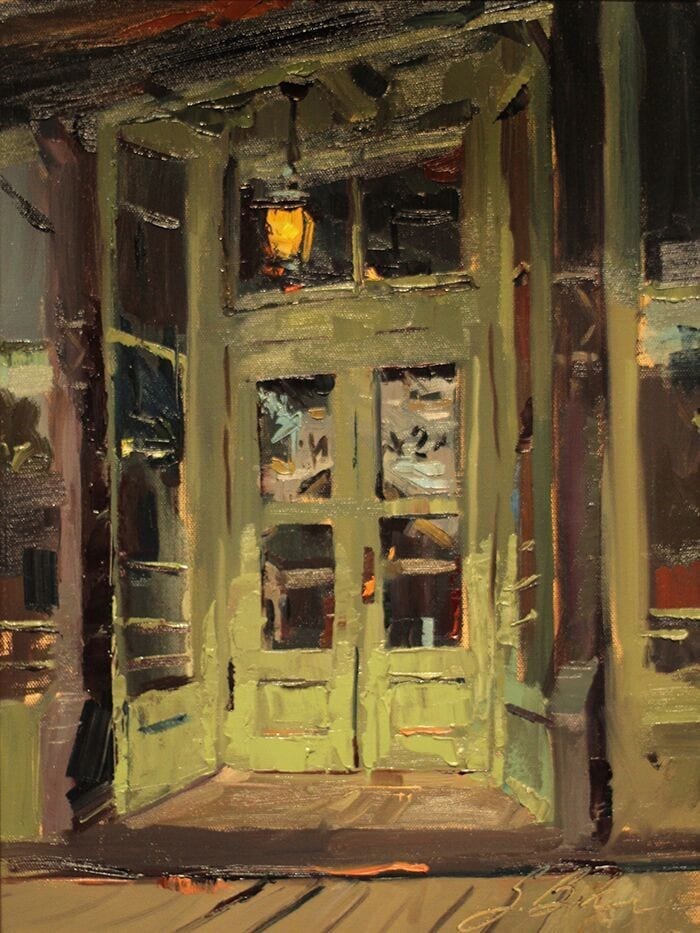

The painting, “A Negative View of Saloons”, was surely a runaway favorite, as it is phenomenal.

She is a woman of high energy and enthusiasm; you can see it in her work. She’s also the newly elected OPA Vice President.

I wanted to interview Suzie a few years ago, but she refused…giving some lame excuse like, “Not qualified, not ready”. Well, in my book she was ready then, but now, even more so. She’s won a ton of awards…wins something in just about every competition she enters. She has plenty to offer. You’ll enjoy this.

How has your advertising background helped you as a fine artist? Working as a designer and then an art director, the “real world” gave me exposure to a professional environment as an employee; then, the stakes were not as high as going it alone as an independent artist. The value of working in a professional environment, using design and photo editing software on a daily basis, prepping jobs for print, meeting with clients, and directing illustrators and photographers were all valuable tools I could bring to bear as I segued into being a full-time artist. My design work and painting overlapped some too so that I could supplement those early lean years with design income.

Your landscapes reflect an absolute joy of painting, is that because they are rapidly painted or is it something else? I’m glad you see joy in my work. It is an intention of mine that my work have a spontaneous, confidence to it, but like Dolly Parton says, “It cost a lot of money to look this cheap!” Similarly, it takes a lot of planning to look this spontaneous.

Do you believe one’s style of painting reflects their personality; if so, what’s your style say about you? I suspect one’s work must be an amalgamation of personality, life experience, training, social/historical trends and market forces. I first landed on my preference for direct painting in college. While we learned to paint in the layered approach of the old masters, we also learned to paint in the direct manner of Manet and the Impressionists. I can point to one assignment that had a profound effect on my painting style. My professor, Peter Jones, arranged two still life’s of simple flower cuttings in glass jars. Once our palettes were loaded and brushes were ready, we had 30 minutes to finish each painting, one right after the other. I didn’t have time to overthink, I just painted. The result of which was a revelation of free and expressive mark making that I strive for even to this day. I feel like I need to qualify this experience with a note that I had already had extensive drawing experience and instruction, many painting classes, as well as color theory and design, and so forth. If my professor had given this assignment on the first day of Painting 101, I suspect my memory of it would have been one of discouragement rather than exhilaration.

Continuing with that thought, do you think one’s personality can be a limiting factor in the type of work they’ll create? I can only speak for myself here, but I would have to take medication to paint in a hyper-realistic way, or as the old masters did, with layer upon layer of glazes. I feel overwhelmed just imagining myself painting that way. However, I sure do admire when others do it well. I think the primary limiting factor in the work we create is not our personality, but rather the junk we throw in our path that stops us from creating in the first place. Steven Pressfield calls all that junk, “resistance”, in his book The War of Art. This book should be dog-eared and highlighted; if an audio book, it should be a part of every artist’s bookshelf or digital library…and listened to regularly. It’s a good ol navel-gazing romp that leads to the kick-in-the-pants we need on a regular basis. Also, check out, Art and Fear, by David Bayles and Ted Orland.

There are many differing opinions as to what qualifies as a plein air painting: in your mind, what qualifies? I think the definition matters most in plein air competitions where painting in the open air from life is the stated, or at the very least, implied expectation. They stamp blank canvases for a reason after-all! “En Plein Air Texas” specifically stipulates in their rules that no photography may be used in the production of competition paintings. An artist might however touch-up or minimally fix a troubling passage in a painting, away from the scene. I have no problem with that, but I do take issue with an artist who substantially paints their canvases in the comfort of their host home. If I’m out freezing, or sweating, or up at the crack of dawn, they should be too!!!!

When you paint en plein air, what do you hope to accomplish? I’ve got two answers for this question, depending on the circumstances. While painting at a plein air event/competition, first and foremost, I want to paint a worthy painting, a painting that I would be glad for a collector to purchase and hang on their wall, a painting that requires no qualifier of, “It was painted in 2-3 hours.” The long-term merit of a painting will not be judged by how quickly and in what circumstances it was created; all that matters, in the end, will be its merits as a piece of artwork. Its distinction as a “plein air piece” may be just an historical footnote. Plein air painting, with its challenges and potential limitations, should not be an excuse for substandard artwork, rather, it is incumbent upon the artist to create quality paintings within those limitations. I’ll expand on some of the strategies I use to combat these limitations in some of the other questions. Secondly, if I am on a painting or hiking trip with friends, or out scouting, my goals will be to collect information, experiment, and practice. In those situations, my panels are usually small, 9×12 or less, and might end up going into a frame or just serving as a color study for something larger.

Many of your landscapes involve very transitory lighting/moods; how do you capture that en plein air? The light at dawn and dusk is particularly appealing but exceptionally transitory. I would typically choose a smaller canvas in this circumstance, but there is a trend in plein air competitions to paint larger. I face these challenges in a few ways. I paint small oil sketches while scouting to get the idea, composition and colors sorted. I use an app called “Lumos” to see where the sun will rise and set…to take out some of the guesswork. I tone the surface ahead of time in a way that will support my idea for the finished piece. I arrive early to block-in the major shapes of the painting so that when the moment arises, I can quickly paint the most fleeting light effects, and finally, I often return to the same location with the same canvas for multiple passes.

Please explain your painting process. Let me answer this in terms of my plein air work, since that has been what we’ve talked about most here. I’ve found the following habits to be just as important to my finished paintings as the actual brush to canvas steps. Here goes: If it is my first year at an event, I try to arrive early and scout out the area. The first year is always the most intimidating, and scouting allows me to come up with a loose plan of where and when to paint; I say loose plan, because I allow myself to diverge from any charted course if inspiration presents itself. If I am returning to an event, I will review my photos from previous years and think about what I might like to revisit or check out anew. While scouting, I often do quick field sketches in oil or in my sketchbook, making note of the time of day and thinking through compositions. These habits, along with getting enough rest, eating well, and generally taking good care of myself, help lower stress and make me a happier painter! Before getting on location, I prep my backpack and squeeze out/freshen up my paint so that I’m ready to hit the ground running. The painting itself starts with a toned canvas and block-in of major shapes. My common painting method, whether en plein air or in the studio, is to work big shape to small shape, general to specific, big brush to small brush, dark to light, thin to thick.

How do you promote and sell your work other than through galleries and website? This is a good time to ask that question, as earlier this year I assessed how income was generated in 2017. Last year, 72% came from painting sales and 19% from workshops with the remaining 9% coming from prize money and various sources. Those painting sales came from: plein air events, workshops students, direct sales, commissions and galleries, in that order. On the expenses side, travel took the top spot at nearly 30% with art supplies (including framing) at 20%. File that under the category, “It takes money to make money.” Making a living as an artist is a bit of a snow ball effect. You start small and build up as you roll along. Sometimes you have a nice slope to roll down and sometimes it’s more of a slog. As far as self-promotion goes, I have my website; I stay active on social media, including Facebook and Instagram; I send emails out to my distribution list; I have a public profile through Artwork Archive, and I run occasional ads. I enter competitions and consider the cost of submitting to shows a marketing expense. I think attending exhibitions and conventions is a significant element of self-promotion too. These events allow artists to meet and network with magazines reps, vendors, other artists, all while seeing great artwork and presentations.

Here is a quote that, years ago, my mentor Rich Nelson shared with me, that his mentor shared with him. I hope it strikes home with you too. “Making it in this business is a two-step process: Step one, get good, step two, get out there, the better you are at step one, the better step two will go.” Bart Lindstrom

Have you set career goals; is that an important thing to do, and how do you go about achieving them? Yes! I cannot overstate the importance goal-setting has had on my career. Starting in 2010, I began setting yearly goals related to making progress in my business and artistic development. Early on, those goals revolved around getting my digital house in order and advancing the weak areas of my artistic skills. I set goals to enter shows and attended openings and conventions. In doing so, a quick glance at the level of work being produced on the national level in shows such as the OPA National Exhibition and the Portrait Society let me know that I needed to raise the bar in my work. I took a sober assessment and asked myself what was between me and that bar, then set to the tasks of lifting the level of my work. Even now, I look at the year ahead and develop some strategic objectives to complement those earlier goals.

Thanks Suzie for a great interview.

Outdoor Painting

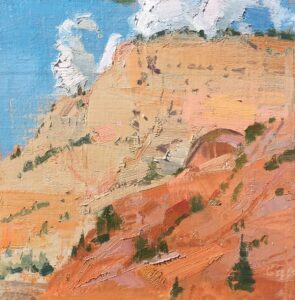

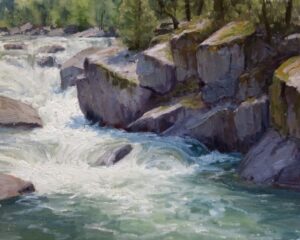

I am fortunate to have been given, several years ago, some 50-70 year-old American Artist magazines. Browsing through one of them recently, I came across an article about direct painting…meaning, paintings created directly from life or nature. In light of the current fascination with, and gushing acceptance of all things done en plein air, the writer of the article brings a little sanity to the topic. I think you’ll find it helpful. All images shown in this article were done en plein air.

by John Pototschnik OPA

10″ x 20″ – Oil

“Direct painting, when practiced by an expert, gives wonderful results; it also imposes stringent rules upon those who practice it. An error of judgement may, probably will, ruin the whole work. For this reason, much knowledge must back up the brush. What must this knowledge comprise?

- The power of visualization must be developed in order that the artist may see, on the canvas, what effect he is aiming for.

- Ideas of color must be worked out before ever touching brush to canvas.

- The ability to draw, not only with the pencil but also with the brush, is mandatory.

- The ability to decide the importance of every object painted, in order to put it down in proper relationship to the whole, is a must.

- Must have a clear understanding and knowledge of masses, of tone, and of design.

“Maybe this long list of requirements will bring disappointment to many; it should not, for every true artist desires to base his work on knowledge. He can only paint what he knows. His development, therefore, depends upon the amount of knowledge he imbibes. That knowledge must be based upon close study of the moods of nature. Never, until nature is thoroughly understood, will an artist paint direct works successfully.”

by Louis Escobedo OPA

8″ x 8″ – Oil

by Eric Jacobsen

18″ x 22″ – Oil

“Nature shows her precious moods for short periods, and only the artist who understands those moods can seize upon them and put them down in paint, with certainty. That glorious period, for example, when the world is flooded with gold, just before the sun begins to set, must be understood to be painted; the artist must have observed this effect often before ever he can paint it in the time nature provides. The mind must be stored with those observations so that, when a scene presents itself opportunely under such conditions, he can set to work, backed up with the information provided by earlier study.

“Knowing the characteristics of each mood of nature enables him to apply them to any scene. If he puts down those characteristics, he has seized the mood, however roughly objects are drawn.”

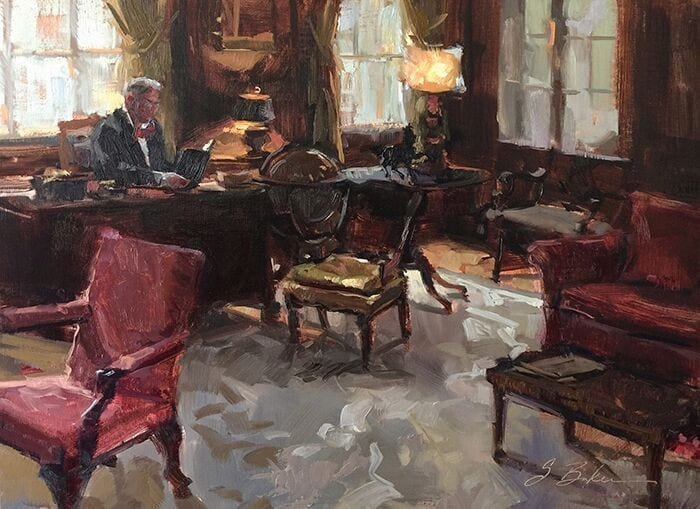

by Suzie Baker OPA

10″ x 30″ – Oil

“The beauty of the subject relies not upon detailed delineation of the objects in the scene, but on the effect of a certain light upon them; hence, direct work must seize upon the object, arrangement, and effects of light, but mainly upon the last two. Nature will not allow the artist sufficient time to draw everything perfectly; indeed, if it did, detail would be so intricate that it would surely kill the fresh, pure effect the artist desires to incorporate in his work.”

“The “bloom” of color put down in one stroke and left, is something well worth striving for. Few can do it well. Success in this means certain mastery not only of brush and color, but of knowledge.”

Kapalua Bay”

by Dave Santillanes OPA

9″ x 12″ – Oil

by Roos Schuring

9.6″ x 11.8″ – Oil

by Kathleen Dunphy OPA

16″ x 20″ – Oil

by Jennifer McChristian OPA

9″ x 7″ – Gouache

How does one become an accomplished landscape painter without direct study of nature? The simple answer…you don’t. Painting and sketching directly from nature, and spending time just observing, are probably the most important habits of the landscape painter.

by Fran Ellisor

14″ x 18″ – Oil

by George Van Hook

30″ x 40″ – Oil

Here are additional benefits of creating paintings or studies when working directly from nature:

- They’re a perpetual record of where you’ve been, what you’ve directly observed, and what can always be referenced when needed. They also help recall the moment it was painted and all the circumstances involved.

- Direct observation becomes more deeply ingrained and remembered.

- They create a deeper learning experience because more time is spent observing and attempting to faithfully represent the subject.

- Compared to working from photos, more senses are involved; not only sight, but also sound, smell, and touch. Even with improved photo technology, the eyes still are able to discern subtleties that the camera cannot.

- They provide a direct interaction with the subject; it’s like speaking to someone face-to-face versus reading something someone else wrote about them.

The next step is yours…assemble your painting equipment, head outside, set up, and get after it. Your efforts, over time, will be well rewarded.

Nancy Boren interview

I don’t remember when I first met Nancy Boren, but it was many years ago. I actually met her parents, Jim and Mary Ellen Boren, before I met her. It was in 1984 that I met them after being invited to go to Spain and Portugal for two weeks of painting with a group of amazing artists that annually participated in the Western Heritage Sale. They were on that trip.

Jim Boren was the first art director of the National Cowboy Hall of Fame in Oklahoma City. He provided expertise and leadership in assembling the Hall’s fine art collection and exhibits. In 1968, he became a member of the Cowboy Artists of America. His favorite medium was watercolor. So, Nancy grew up around art and the western themes painted by her father. Although she has found her own voice, the influence from her childhood remains. At this year’s Oil Painters of America National Show, Boren was a huge winner, taking the Bronze Medal and Artist’s Choice awards for her painting “Thunder on the Brazos.”

Her greatest passion as an artist is figure painting. Although she has many interests and her painting subjects do vary, she’s most attracted to sunlight and often depicts her subjects in direct light. Three artists she would like to spend a day with are: Nicholai Fechin in Taos, Emily Carr in a British Columbia native coastal village, and Childe Hassam on Appledore Island.

When I asked her how she typically works with clients that commission a painting, I really enjoyed her answer. In a humorous way, I am contemplating just which dogs she might be speaking of. “I almost never do commissions. My heart just isn’t in it. I used to do pet portraits, and when I did those, I would take lots of photos in different lighting situations, then do a 5 x 7 oil sketch. After approval, I did the larger painting. Occasionally the clients also bought the sketch to take to their office or lake house. Much patience and time was required; however, I really did meet some great dogs.”

I know you’ll enjoy this interview with Nancy Boren; with pleasure I bring it to you.

30″ x 24″ – Oil

(Bronze Medal, Artist’s Choice Award – 2016 Oil Painters of America National)

What is your definition of art?

Art is a creation that must contain beauty. Not necessarily beauty in the subject, but in the presentation and execution of the idea. John P. Weiss says that people long for beauty and creative expression. They want to be moved, inspired and shown the hopefulness of art and I agree with that.

“I have had the great good fortune to be born in a place and a time where the luxury of being an artist is a possibility. I am one because I have the opportunity to be what I was born to be.”

Your Dad was a well-known, very accomplished artist; what influence did he have on you becoming an artist and doing the type of work you’re doing today?

He was a huge influence. I grew up seeing him happy, productive and successful. Like him, I also enjoy doing art in a traditional vein and have been familiar with wide open spaces and western subjects all my life. Of course I also paint more exotic figures from time to time.

30″ x 32″ – Oil

When I started doing the pieces for my first show with my dad in about 1978 for some reason (safety?) I did ink and watercolor wildflowers similar to botanicals. Next I started doing watercolors of old interesting buildings, the Taos pueblo, and landscapes. I had used wc growing up and my dad did watercolors as well as oils, so it seemed easy and familiar. In college at Abilene Christian we never did an oil, only acrylics in the painting classes and I found I didn’t like acrylics at all. I later started painting in oils, I don’t even remember how that came about, I just did it. I didn’t want to do the same subjects as my father, but I was in the same galleries so it was a bit perplexing as to how to establish my own identity. I just went at it one painting at a time, but I liked cowgirls — I lived in Texas for goodness’ sake — and so I finally started doing them because that was a western subject my dad never did. Costumes and hats appeal to me in figurative work so it was a perfect fit.

You seem to be equally attracted to landscape and figurative subjects; what is the attraction to each?

I love figure painting the most, but I love landscapes also. One is a nice change from the other. I need variety.

Maine (Plein Air)

9″ x 12″ – Oil

(Finalist, Bold Brush Competition –

Dec. 2015)

I do paint from life and attend figure painting sessions but most of the paintings I put in shows are done based on photographs. Some would just be impossible for me to do otherwise — especially people on windmills or figures jumping.

34″ x 38″ – Oil

(Gold medal for Signature Members of American Women Artists Show – 2016)

“I hope my work shows how intriguing I find the world.”

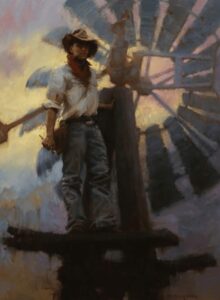

You have created several very impressive figurative paintings with windmills…very interesting and compelling compositions. How were these set up and accomplished?

I decided I wanted to do a windmill piece and so I googled windmills. I found a place a couple hours from me that has a whole group of them and the public is welcome. I take my models or have them meet me there. Then I stand on the ground and direct them, and take lots of photos.

Do you have a pretty clear concept in mind before beginning a painting; if so, how do you work out your concepts?

I usually do have a clear concept in mind. I do most of it in my head. I may cut up a photo I have printed out, or paint over part of the photo, or do some erasing in photo shop (but I am far from a tech guru so the simple way is how I approach it). I know people tout the great benefits of thumbnails, but every time I try them I get annoyed and disgusted because they don’t look anything like the finished product I want and so as a result I would rather work out things on the painting itself. I try to look on the bright side, because when I leave bits of the original color showing through and around the changes, the painting is actually more interesting than it would have been had everything been perfectly planned out at the start. At some point after you learn how to do things conventionally and correctly, you have to embrace your own quirkiness and go with it. For a few larger paintings, I have done small studies (8 x 10 up to 12 x 16).

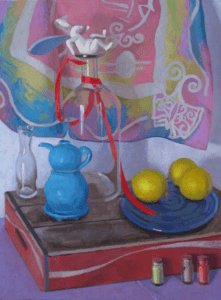

12″ x 16″ – Oil

(Honorable Mention, Plein Air Southwest Salon – 2016)

20″ x 36″ – Oil

How do you come up with your ideas?

Two ways: I see something that would make a good painting, or more often, I set my mind to work on coming up with something. I think while I drive, and I look for things to spark ideas. I love this quote by Thomas Edison: “To be an inventor you need an imagination and a pile of junk.” My junk pile is composed of colors, shapes, outfits, people, weather, animals, stories, and props. I love treasure hunting on back roads, antique stores, on walks with my dog…everywhere. One fascinating object can give me a painting idea.

What is it that you primarily want to communicate through your work?

The immediate answer would be for each painting to convince a collector to take it home. But the larger answer would be sharing an honest delight in the world and the hope that my slice of life will resonate with someone else out there. And I hope that the blood, sweat, and tears that went into it are transformed into convincingly light, right strokes of paint.

“Artists of all kinds add the spice, the eye-opening moments, the richness to life.”

What’s the major thing you’re looking for when selecting a subject?

Many times I think in terms of silhouettes. An interesting silhouette like a windmill always grabs my attention.

Please explain your painting process. Does the process differ when working plein air versus studio?

I pretty much start the same way no matter what color scheme, size, or location. I draw with thinned oil paint (often a transparent color like olive green or a mix with transparent oxide brown) to get all the big shapes in place, sometimes on a toned canvas, sometimes not. Then I use more thinned paint to get the darks and colors suggested before beginning to paint with thicker pigment. Lots of times I start with the focal point, but sometimes I work around it. I would say it is the approximate trial and error system. I can’t completely finish one area with white canvas surrounding it before going on to finish another area; that just does not work for me.

36″ x 24″ – Oil

silver metal leaf

16″ x 20″ – Oil

How do you decide on a color scheme for each painting?

If I see something beautiful I may try to replicate the effect, so the subject informs the color choice. Sometimes I want to paint something red because I have just finished a painting with a lot of green and I am sick of green. When I am frustrated with color I go to a limited palette to give my brain a rest and to enjoy the subtle surprises those color schemes hold.

What colors are typically found on your palette? Why these colors?

Zinc-titanium white mix, cad yellow light or medium, cad yellow dark, orange, yellow ochre, cad red light, permanent alizarin, sometimes cad red deep, burnt sienna, transparent oxide brown, cobalt or ultramarine blue, sometimes manganese blue, sometimes olive green, ivory black. Sometimes a few others also, but I don’t use everything on every painting. I use a Zorn palette on occasion. Through the years colors have come and gone.

What are the compositional guidelines you always adhere to when

designing a painting?

I doubt I always adhere to any guidelines. I do try to stick with odd numbers of things instead of even and I try to use repetition. I try to have only 3 or 4 big areas of value.

I have attached the original photo I used that I took with my cousin posing on a windmill as well as the 16 x 12 color study. The photograph shows that is was an ugly gray day with virtually no color in the sky or anywhere else. As we drove away, the sun snuck out from between the clouds for a moment and so the sky was reconstructed and enhanced from my quick glimpse of it.

The photo, used as reference for “Aloft in the Western Sky”, shows Boren’s cousin posing on a windmill. Next to it is her 16″ x 12″ color study. Boren says it was an ugly gray day with virtually no color in the sky or anywhere else. As we drove away, the sun came out from between the clouds for a moment, so the sky was reconstructed and enhanced from my quick glimpse of it.

How has your plein air work informed your studio creations?

Cameras are great for detail and lots of information, but plein air studies are great for feeling and color. I have done paintings using a combination of the two: plein air for the color and photos for the arrangement (especially of things blowing in the wind).

Do you have a marketing strategy for promoting your work?

Perseverance is always key. I try to do quality work, get in quality shows and galleries. I do have a web site, which I keep reasonably updated. I post on Facebook and Instagram, and I enter competitions, as well as belonging to several national groups. Good things have happened as a result of several of those areas. Honestly, I am more concerned about my next painting than about my next marketing effort.

Start today. Even if you can only work a short time each day, start. And use what is at hand, like the children. They will grow up so fast, time is of the essence. A tremendous amount can be accomplished in small spaces and in small blocks of time and there is nothing wrong with doing small pieces that can be finished quickly. Donna Howell-Sickles used to get up at 4:00 in the morning to have two uninterrupted hours in the studio before her daughter got up. I don’t know that I would have had that kind of dedication but I do believe in just doing it; figure it out as you go.

If you were stranded on an island, what three books would you want with you? How to Survive being Shipwrecked and Get Rescued, one of my scrapbooks of art I have clipped out of magazines, and Night Circus.

What’s a typical day look like?

Every day is different. I do love days when I don’t have to leave the house (where my studio is) except to take a walk. I often run errands in the morning because I am an afternoon person. My husband gets home from work at 7:00 so I can get a lot done after lunch.

Nancy, thank you for a great interview. Your plain spoken, down-to-earth responses will be greatly appreciated by the readers of this blog.

Elizabeth Pollie interview

Her paintings are easily recognizable, varied in subject matter, and unique in composition, color, paint application, and texture. Surely they are a true reflection of her personality which she describes as slightly unpredictable, playful, yet belying a serious side…"A bit hard to put your finger on", she says.

Showing her sense of humor, she perceives her strength to be, “thinking outside the box”, but then the problem is, she has no idea where she put the box. I wondered how she determined her painting prices and if the popularity of a particular subject influenced her painting choices. She doesn’t select subjects based on popularity, instead she just allows herself to paint whatever intrigues her. That reality shows in her work, and I believe that’s why collectors and artists are drawn to what she does. When pricing her work, she looks at the price structure of other artists at her level professionally

and prices her work similarly.

Pollie approaches life enthusiastically…”feeding her wanderlust.” She likes this quote by poet, Wendell Berry, “Nobody can discover the world for somebody else. Only when we discover it for ourselves does it become common ground and a common bond, and we cease to be alone.” I don’t think Elizabeth Pollie needs to ever be concerned about being alone.

I was primarily involved in the editorial arm of illustration. This was the arena where one would be commissioned to create a book cover, a series of illustrations for a magazine article, etc. It was, to some degree, “The thinking man’s” category. It was a glorious time in illustration given the amount of creativity artists were allowed. Metaphorical thinking was often a part of the equation. This gave rise to some brilliant images. Brad Holland was a hero, as well as many others.

I think there have been times in history when illustration, in some ways, exceeded what was concurrently happening within the fine art world. Often the requirement of strong technical skills along with the ability to go beyond literal translation can make for some very evocative imagery. However, I do not miss illustration given that it was so highly competitive and was vanishing rapidly as more and more art directors turned toward quick and easy digital solutions. I would like to think that when you turn a new page you might unwittingly bring along with you the most meaningful, delightful and essential passages.

How difficult was it for you to transition from illustration to fine art?

It was no effort at all. I had moved to Northern Michigan leaving behind many things. I was no longer teaching illustration at the College for Creative Studies and there was nothing I could blame as an outside distraction.

How would you define art?

There are many impersonal ways of defining art. Francis Bacon said, “The job of the artist is to deepen the mystery”. I love that. I think that it involves creating something that when offered to the world somehow enlivens the senses in a sublime manner.

John, I don’t think there is a “Why ?” Those were the seeds I was born with. I have no question about it. This may be my one truth. As far as what motivates me, I think it’s a slightly obsessive love of possibilities within the realm of representational imagery and trying to come up with an interesting and evocative solution.

“The world is full of wonder, mystery and any number of subtle connections. As a visual artist, I love exploring the nuances found within the confines of ‘the everyday’. The artist, Paul Klee is quoted as saying, ‘One eye sees. The other eye feels’. This dual lens is what comes into play when painting any subject matter. I believe the best paintings arise from the ability to balance what is easily observed with what stirs quietly just out of reach. It is the unspoken yet deeply felt nature of things that leaves me continually inspired.”

How would you describe your painting style?

John, I would have to leave that to the critics. I don’t really think In terms of style because there are so many ways to represent something in two dimensions, yet by comparison there are relatively few ways of describing one’s style.

This evolution feels very natural. Really I think that all artistic evolution is a form of response to a combination of personal history and experience, current conditions, and ongoing stimuli. In truth, I sometimes feel more at the mercy of this process than assuming that I am behind the wheel.

You paint a variety of subjects; why is this important to you?

Admittedly, I have a restless spirit. On certain levels, how one thing relates to another often attracts me more than the subject matter itself. And, I think any subject can be imbued with a sense of mood, mystery and some kind of beauty. I recently saw a painting of a couch and it was simply gorgeous – the painting that is, not the couch. Put 10 great writers in a room and ask them to describe a glass of water sitting on a table. If you are mesmerized, it was the description not the actual object.

Animals represent an important part of your repertoire, what is the connection?

I was the girl who brought home every stray, filled her bedroom with stuffed animals and named each one, dreamed of having a house full of cats and dogs ( and subsequently did). It’s impossible to describe how deeply I love and respect the animal world. Nor can I describe how I feel when I stand and watch them – it goes deep. Still, when I paint animals, I always begin by looking at them as a shape among shapes. As the painting develops the mood of the piece begins to come forward. With hope, nuances and layers that might describe my connection to them are woven into the initial structure. I hate the idea of simply painting a cute cow. I love the idea of painting the essence of something lovely.

I focus on 3 things; design, light and mood. Design is the plot, mood is the overall feel of the story (the emotional core). Color, value, brushwork, surface, these are how one gets there.

Do you have compositional principles that you always adhere to?

No, but my tendency it to crop in and think of everything as a still life. I have no issues with moving, creating and getting rid of elements to strengthen the composition. I tend to prefer my compositions to be a bit more spare than busy…more quiet than noisy.

“Although my work has a very analytical side to it, I am probably more prone to be swayed by intuitive impulses. If you can see in your mind’s eye, then at least you can head in that general direction. I have never been someone who relies on technical information. For me, painting is an initial idea followed by a series of questions and the answers that come up along the way. Every answer gives birth to a new question.”

You seem to give considerable attention to paint application and the surface quality of your paintings, why is that important to you?

I recently heard an interview with David Hockney. He mentioned that the first thing he looks at when viewing a painting is it’s surface! I think surface has a power all it’s own. It feels as though it has a magical kind of DNA. It contains traces of its creation; its own private history. How could one enter the Colosseum in Rome and not want to touch everything? How can you walk through the woods and not lay your hands at least one tree? I think in many ways our eye’s touch paintings, and even though they are always thought of as 2 dimensional, the surface lends a new subtle dimension.

Composition and drawing are primary and equal in my book. Next I would say, value, technique, color, edges, framing. Concept is integrated into and guides all of these elements.

What colors are typically on your palette; how/why were these colors selected?

I use eight to nine colors… a warm and a cool of red, blue, yellow, plus white, asphaltum, and a few oddball colors. I also try to have at least four transparent colors on the palette. This allows me a great deal of color harmonizing, push and pull, as well as the ability to enliven the piece with pure chroma.

Do you have a color philosophy or is your choice of color, while painting, intuitive?

Primarily modulating within a chosen scheme…warm and cool, transparent and opaque, darks and lights. So, even if it’s a warm painting, I still will play with relative” cools”. When it comes to pushing color and mark making, it’s quite intuitive and far from predictable.

I have never been someone who adheres well to any kind of routine. Because of this I don’t begin all pieces the same way. I don’t really have a method. I sometimes start by laying down color, letting it dry and then choosing what to paint over it; that gives a diving board. Sometimes I draw something in and then throw down a color that will set up something to play off of. Again, the main concern is the design; it is not alla prima. I work all over the canvas in pretty thin layers, usually building up to a few areas of thicker paint.

“I think surface has a power all its own. It feels as though it has a magical kind of DNA. It contains traces of its creation, its own private history”

Do you consider the process of painting more important than the result?

Results, being the sum of the effort, matter greatly to me. The process, being the journey has it’s own personal value but I am not at all attached to it. I often find that I am vexed by my own circuitous path. At one time, I thought that my time in front of the easel might become easier as my knowledge and skills grew. In fact, it’s just the opposite. As my understanding has grown so has my desire to improve my paintings. As ones language grows so does the variety of choices regarding how they might articulate their thoughts. And so it goes.

What’s the most difficult part of painting for you?

Trusting that the audience is smarter than I think. The human brain needs very few visual clues to piece something together. I sometimes think there is more power in what we leave out versus what we choose to include. Poetry is a great example of how very few words, used in brilliant combinations can create something utterly sublime. Finding this balance in painting is greatly challenging. I think tiny nuances have great impact. Knowing when and where to weave these in can be utterly confounding.

My father loved art and architecture. It was a language that was spoken in our home. And, I was lucky to grow up spending nearly every Saturday messing around in art rooms that were connected to our local museum. I could wander into the museum and spend time perusing the various collections and special exhibitions. There was a Cassatt, a Sargent, a William Wendt, an Andrew Wyeth and several Hudson River school painters. By the time I went to art school I had my own inner-catalog of favorites. At eighteen, I loved Francis Bacon and then Edward Hopper. In my twenties I was smitten with American Regionalism (Grant Wood, Thomas Hart Benton , etc.) and the Canadian Group of Seven.

When illustration became my primary focus I delighted in the illustrations of N C Wyeth, Howard Pyle, Dean Cornwell and Frank Brangwyn, and the line work of Arthur Rackham; this was all before I was thirty. As the years passed, more and more artists piled in and continue to do so on a regular basis. I suppose it’s one big happy family that continues to grow and help inform my own visual vocabulary. Perhaps that’s why I am never lonely in my studio, at any one moment in time there’s a pretty big crowd milling about in my head.

I think the best use of influence is to receive it in the form of inspiration. If something trickles down, I’d prefer it is almost unconscious. The one thing I avoid is looking at anyone else’s work while I paint because I find it can undermine my sense of trust in my own instincts.

I don’t really have a clear answer for that. I would suggest that an individual who is in the earlier stages of their development not attach too firmly to one artist. Instead, I’m inclined to encourage people to fall in love with art history. Of course, learn about the craft but I think there is something profoundly important about knowing how one art movement gave way to another. There is always something to be learned by reading about the struggles of noted artists. Drink it all in. It’s so rich and relevant on many levels. Go to museums. Be dazzled, amazed and curious. Take this same awe and curiosity with you wherever you go; carry it with you into the woods, up and down the aisles of the grocery store, down along the railroad tracks, this can only enhance and expand your own point of view which is always there waiting to be expressed in it’s own unique way.

“I don’t feel all that successful as an artist. I think the way I measure personal success is pretty complex and I feel I have such a long way to go.”

Anybody’s guess. I have some health issues that from time to time cause pretty big fatigue. This only means my days start later and I might struggle a bit with focus. Turns out, energy is a rather wonderful thing. But all in all, I feel so lucky to get up in the morning and look out over Lake Michigan. It centers me. On my drive in, I often stop to say hello to a group of cows that I pass everyday. That just makes me happy. I have lunch with my husband. And, finally when I find myself in front of my easel I usually stay there, for better or for worse, and have a good long go at it.

What is West Wind Atelier?

West Wind Atelier was the name of my first studio in Harbor Springs when I moved to Northern Michigan. It was where I worked, taught and exhibited my work. I’ve since moved to a different studio and I own a gallery named Elizabeth Pollie Fine Art where I sell my work and represent Marc Hanson, Mark Horton, Derek Penix, Kathleen Newman, and Shannon Runquist.

Many thanks to Elizabeth Pollie for this beautiful interview. Why don’t you let her know how much you appreciate her sharing part of her life with us?

Melissa Hefferlin, Daud and Timur Akhriev interview–Part 2

I’m pleased to present the second part of this special interview withthe Akhriev (Ak-REE-ev) family: Melissa Hefferlin, husband Daud Akhriev, and son Timur.

In Part 1 we learned how Melissa, as a young 20 year old American made her way to Russia to study at the Russian Academy of Fine Art, where she met Daud. We also learned of the extensive training the Russian Government provided for its promising young artists. Daud and Timur are products of that system. All three are multi-talented, speak several languages, are trained in a variety of disciplines, and recipients of many awards. Daud and Timur were big winners in the Oil Painters of America national competition, held earlier this year in Dallas.

The final part of their very interesting interview deals with their diverse cultural and religious differences, how Daud and Melissa met and eventually married, and how their work has influenced the other. Timur shares his first impressions of America.

I know you’ll enjoy this. It’s a great story. Be sure to read Part 1 Here.

Melissa Hefferlin

Daud had friends in my studio at the Academy, and so would sometime enter our studios to meet his friends for lunch. He asked them to invite me to his place for a dinner party, and I was smitten with his larger-than-life sense of humor and passion for painting. I also loved his work even then. He had ten times more of it than any of his colleagues (he was a graduating from the last year of the masters’ degree). I thought then that I’ d love to see him painting in the States with such huge talent, and not struggling to get by in the then-very-broken Soviet Union. Luckily, over the next four months, we spent a LOT of time together, and very quickly were inseparable. At the close of the school year when my time was finished and he was graduated, he accepted my invitation to “visit” me in the States, and we have been together ever since. It’ s true, though his family are Muslims from the Northern Caucasus, and I come from Seventh Day Adventists in Appalachia, we found that the values of hard work, love of family, mutual respect, doing all things to the best of your abilities, and passion for life were powerful overlaps. These overlaps are true for our extended families, too, and I am happy to say that our blended family of mixed heritage now adore one another powerfully. Of course sometime we had misunderstandings, but all families do. I wish more Americans had the opportunity to form bonds with people who seem different from themselves, as it is a powerful opportunity to grow and experience a broader spectrum of human life.

Of course working near one another means we absorb something of the other to some degree. Daud most obviously gave me his work ethic, and understanding of the hours necessary to put into a finished studio piece of any profundity. My American education had shown me turning in work which at most had ten hours in it over the course of a week. Now I can spend months on a larger painting, or visit a piece off and on over a year to get it right. Before I lived with Daud, that sort of time expenditure was not within my comprehension. I also continue to learn from both Daud and Timur to be more mindful of composition. I’m an intuitive composer, and they both are much more mindful and methodical and intellectual about their compositions. (Cindy Procious, a painter currently residing in Chattanooga, is another fine sounding board on this matter to me.) While my instincts about composition remain a powerful guide to me, I do enjoy examining my choices from the perspective of Timur and Daud, and tweaking. You didn’t ask me about Timur, but I am now being super inspired by my son, who I think is just on fire. He’s super dedicated to painting things that are true for him, and not necessarily just beautiful. His series called “drifter” uses my nephew as inspiration/ model, and I admire that body of work intensely. Timur’s malcontent view on many modern practices, and on the world handed down to his generation, I find very “true,” and powerful, and I am inspired to do better. I love Timur’s color!!! Damn, that boy is a colorist. With Daud, I know in an obvious way, I gave him pastels. Daud hadn’t ever considered pastel seriously, nor had access to good ones. Now he’s an ace pastel painter, I’m proud to say. Also, when Daud was doing his masters in Russia, he was very monochromatic on purpose. He was wondering, how little color could he use and still say something well. I urged him back into his full spectrum of color. I also sent him out to paint landscape, which he’s thought of as school exercise. He blossomed and changed technically as an artist after a couple of years doing plein air all over the States and Switzerland, wherever generous people let a young couple visit and make art. I really did nudge him to do that, though quickly he took the bit in his teeth.

How would you describe the work you’re doing today?

The purchase of a studio in Spain has given me more time to focus on pieces in an uninterrupted way. I am enjoying exploring still life and figurative pieces more deeply. I have more time to finish things not necessarily more “polished” like Ingres, but more deeply to my liking. Exposure to an entirely new visual culture has been a shot in the arm. I love painting the flamenco friends I have, and the Spanish horse culture. I am really enjoying putting more love into my block printing. My subject matter is divided between still life, which is a real love of mine. I’m attempting to get more soul into still life, so that it’s less decorative and more soulful. And then I am painting lots of horses, riders and flamenco women. These are the things I love, the part of my life which gives me joy. So I want to paint them. I’m enjoying experimenting with glazes in oils, and then switching in the next painting to alla prima brushwork. I’m loving being a middle-aged painter, and having some skill already to where the media works with me, and playing is actually fun versus agony. I’ve also had some wonderful private students, long term students, and working with a new artist is always a fresh examination of what one believes. This has been fortifying.

Daud Akhriev

I was born into a family which followed traditions of Muslim heritage, but I lived in a village where there were representatives of almost every religion on earth. So living in the USA was very much like the way I was raised. The country being officially atheist did not mean that people were not privately believers, and in our village many people believed in their own home, privately, and the same is true in the USA, but though privacy is not necessary of course. Once being educated, all my best teachers were Jewish or culturally Christian (practicing to a more or less degree). So really, in that particular way, nothing much changed. I think the reason nothing changed in that department began with my first grade teacher, and then again with Zhukov in the children’s art school, I was always taught that “you are just another block building in humanity’s cultural achievement. Your job is to be strong and honest. When a child is so taught and so treated, that is a clear directive, and the atmosphere around the child who later becomes an adult is really not very important.

Multi-faceted. I am doing many things simultaneously right now, all due to travel and the experiences which travel provides me. When I’m able to see different nature, and have new dialogs with artists and musicians and non-artists, I get new ideas for materials and subject matter. In the last two years I was in Italy, Maine, Andalusia, Russia, Morocco, and the countries expose me to so many art forms. There’s always painting. I’m working with oil and tempera now, which helps me to sharpen different skills. Working on a trip in watercolor makes you more direct and fast. Travel paintings I bring to the studio as reference material. I’m also working with clay sculpture, tile designs with drawings in wet clay tile. I still continue with one of my favorite series, called “Weathered People,” using lots of different people from around the world, including many fishermen. Within the “Weathered People” is a subset of paintings called “Wanderers.” I just finished a painting of a wanderer who was a weathered, troubled person who struck out on the road to wander, like a Hindu mystic, and he wandered and was beaten up by the elements, and had adventures, sad, happy and varied, and after years on the road he’s about to arrive home, finally at peace. My wife, Melissa, came in to the studio and made me very happy by saying, “Oh, he’s a peaceful man.” I like this series the best. My piece in the last OPA show was from that series. For the last two years I’ve been making and installing public mosaics. Mosaic helped me a great deal to express my affection for decorative art. It was so freeing to manipulate form in a non-realistic way. I enjoyed making my own ceramic tile for the mosaics, and then combining my tiles with Italian smalti, which are so rich in color and light.

Name three of the most significant things that have made you the artist you are today?

My teachers, my family and my friends. My personal connections set the tone for the artist’s vision. My teachers set the tone of ‘you have to know how to learn.’ They said to me, “Imagine that you are a sponge and collect all that you can, then release what is not useful.” However, you have to collect information first. My family and friends require of me to do what is right. My relationships with them help me discover what the right way is, what topics are important. That helps to shape my course. Perhaps I would add a fourth, the ability to travel. Travel allows me to meet people, see great art, and have conversations, testing what I believe and do…and of course, analysis of all input is essential.

Timur Akhriev

The United States was great from the first time I ever set foot in this country. It was so different from Russia. I remember driving for the first time through Atlanta, I could not believe myself how amazing everything around me was. And, to this day, whenever I fly back from any place in the world it still feels more like home than any other place. America is a beautiful place.

I think we all have our influences that lead us to be who we are as artists. Russian school gave me a great training, but when one has two great colleagues (Melissa Hefferlin and Daud Akhriev) by your side its a great opportunity to learn more. As Akira Kurosawa said, “If you want to be a professional you have to remain a student.” I believe there is no end to how much one can learn and move forward, even if sometimes you feel like you’re standing in the same spot. I don’ t really know if I found my voice yet, I think I’m still searching.

Thank you, Melissa, Daud, and Timur for this wonderful and interesting interview. I and the readers of this blog are appreciative.