In July of 2013, I asked a group of women artists if they noticed any significant differences in the way male and female artists are accepted within the American art scene. Cindy Baron, one of the women asked to comment, senses there is a difference in how the two genders are perceived in the marketplace. Men are considered to be more serious about their work than women.

Commenting on the difference in support received, Baron notes, “Most male artists have a support system behind them. As women, we have a natural tendency to support everyone around us, and most often we are unsupported or not taken seriously.”

Well, there is little doubt that this Rhode Island artist is totally committed to her work. She is one of the few artists accomplished in pastel, watercolor and oil, while being awarded signature membership status in the American Watercolor Society and Oil Painters of America. Quite an achievement for those that might question her seriousness.

It’s my pleasure to bring you this inspiring interview with Cindy Baron.

Why are you an artist?

It is a vocation for me – I could not imagine doing anything else with my life. Art is about creating beauty, and I have been doing that for as long as I can remember.

If you were not an artist, what would you like to be?

I would definitely be a carpenter. I’m sure that sounds funny coming from a woman, but I love construction, building and woodworking. In my early twenties I helped build a house and learned so much – from roofing to masonry. It was a two-story English Tudor with lots of stonework and woodwork. I truly enjoyed the experience and would love to do it again.

What have been the major challenges you’ve had to face in order to establish yourself as a professional artist?

My biggest challenges have been timing…and myself! I am very hard on myself, many artists are. I am always challenging myself to be better, to see the landscape simpler.

Princess Diana famously said, “if you mess up raising your family, then nothing else matters”. I believe that. I would not be where I am today had it not been for my sons. Through patience, I have gained tremendous passion for my art and it has become clear about where I want it to go.

Your paintings are very atmospheric; what are the key points one needs to know when creating a true sense of atmosphere?

What is the major thing you look for when selecting a subject?

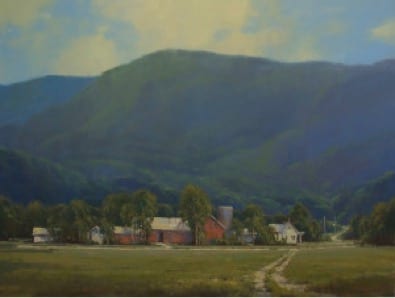

I’m attracted to shapes and edges or drama of the scene. A coastal landscape has the wonderful movement and big value changes. Mountains have all the elements of shapes, edges and subtle changes. I love to draw, so I look for certain edges to focus on and how I can enhance the lighting on it.

When designing a painting, do you attempt to simplify and minimize value masses? How do you determine those value masses?

I will be the first one to tell you I can complicate a painting more than anyone else. Simplifying has been continuous development work for me. This is where my sketchbook and field studies are key. To enhance that, most of my paintings start with just a tonal wash of a warm value and then I work on shapes and decide my value ranges. This has been very helpful to me. I also have a friend in a mirror. I have a large one directly behind me when I am at the easel. I am constantly checking my drawing and painting through this process. It won’t lie.

Please share with us your working process.

Do you consider the process of painting more important than the result?

No, the result is the key. It doesn’t matter how you get there, it’s if you achieved what was in your mind and your heart.

How much of your work is intellectual vs. emotional…and how would you define the difference?

This is a hard one to give a percentage to, but when you are so moved to create what you feel, I don’t think anything can stop you. Intellectually you know the structure of a good painting that has come from time spent in the field and studio. Of course you need both, but passion plays a tremendous role for without it you would just be going through the motions. Most of my life has been spent in the sports arena and it takes a lot of passion, dedication and discipline to succeed, not just athleticism. I apply that concept to fine art; academics without heart and soul would reflect in your creativity.

What colors are typically found on your palette?

Ultramarine Blue, Cobalt Blue, Permanent Red, Cadmium Yellow Med and Dark, Alizarin, Yellow Ochre, White, Viridian, Savanna Gray, Unbleached Titanium, Black

What part does photography play in your work?

Photography plays about 50% and mostly just for reference. I use my painting studies and black and white sketches. Photographs are great to recall or study a shape, but they are not good for values and depth of a scene. That has to come from you and your recall. The last 20% of my painting is done without any reference and I go mainly on my memory of the scene and what moved me to want to paint it.

What part does plein air painting play in your work?

A huge amount, you have to paint in the field just to gain the knowledge of values and color. I love being outside and my trips I plan every year are more like boot camp. This is where the good, the bad and the ugly happen, but so invaluable to a successful studio painting. That hour or two you spend on a painting, you learn what shapes are good, how to hold your masses and color temperature. The knowledge of this can only be achieved through painting on site.

What qualifies as a plein air painting?

I like using the term “field studies” instead of plein air as most of my work is for capturing knowledge. I almost always paint a little on them in the studio without references and go by the memory of that day. Plein-air I would apply to timed painting events that cannot be painted on later and entered into shows. I love to revisit my field studies and paint on them, great knowledge is gained.

How would you define “success” as an artist?

Peer recognition and wealth would be the go-to answer, but it’s not. Yes I am an artist and I believe that is a gift, but most importantly I am a mom, an entrepreneur, a good friend and most of all, ever evolving. Yes there is success, but it came with discipline, hard work, teaching and a feeling of pride that I am allowed to be an artist.

What’s the most difficult part of painting for you?

Probably calling a painting “finished.” I like to look at my paintings with fresh eyes. When you revisit a painting after not looking at it for a couple of days it is so helpful in problem solving.

How many hours per day do you typically paint?

A typical day starts with coffee, emails than exercise. I am usually at the easel by 11 and will paint till about 5. I break for a couple of hours, but I am a fan of late night painting. I paint every day, it is seldom that a day goes by and I haven’t touched a brush, even if it’s just to lay a couple of strokes on a painting that I see has an issue.

What advice do you have for someone desiring to be an artist/painter?

Be passionate, disciplined, determined. Leave the ego behind and always challenge yourself. You will have good times and hard times and even question your artistic abilities more then you will want to admit. Study from artists you admire – living or deceased – and be open to several mediums to find your expression. Being an entrepreneur has many challenges but know that you were given a gift and it would be a sin to not use it.

If you could spend the day with any three artists past or present, whom would they be?

Tucker Smith, so talented, I love the stories he paints. Edgar Payne, for introducing me to the mountains. And William Trost Richards, I cry when I see his paintings.

What has been your most effective marketing tool?

Several things; one being, my two feet. I have had the privilege of living and traveling around the country and would do my research on galleries, museums and artist that were in the area. Making a personal connection has always been a good avenue. Other tools have been Plein Air events, gallery representation, collector lists, advertisements and the Internet.

For more of Cindy’s work: cindybaron.com

For more about the interviewer, John Pototschnik, visit www.pototschnik.com

Interview

Debra Joy Groesser Interview

Debra Groesser is a signature member of the American Impressionist Society, American Plains Artists, and Plein Air Artists Colorado. She’s an associate member of the Oil Painters of America, and American Women Artists…and she’s on the Board of PAAC.

Debra Groesser is a signature member of the American Impressionist Society, American Plains Artists, and Plein Air Artists Colorado. She’s an associate member of the Oil Painters of America, and American Women Artists…and she’s on the Board of PAAC.This folks is your current president of the American Impressionist Society…one busy lady to say the least.

It took several months to finally complete this interview, but I believe you’ll find it worth the wait. I first met Debra a couple of years ago in the Flint Hills of Kansas during a plein air event organized by Kim Casebeer. I found Debra to be a delightful person.

There is more to this interview than shown here, so I will include some of her other comments in future blog topics I have planned. I hope you enjoy the interview.

What’s the correct pronunciation of your name?

Grow-sir.

How did you first become interested in art and what led you to becoming a professional?

I just remember always being interested in drawing. My favorite thing to do as a child was to copy the illustrations out of my story books. I also copied the words and by doing that, taught myself to read at age four. My favorite book was “Barbie Goes to a Party”. I would love to find a copy of it! Back in the days of Romper Room (giving away my age here), they would put pictures up on the TV screen for kids to draw and mail in to the TV station. My mother sent one of mine in when I was three and they put it on TV…I don’t remember it but I guess you could say that was the start.

In my coloring books I always put light and shadow on everything. It was never just flat coloring. I had a friend in 5th grade when we moved to Nebraska who was also very artistic. Instead of playing the usual games that kids played, we would draw for hours. We set up tennis shoes, still life’s, drew the trees in the yard…anything we could find. I just loved it. From there, I took every art class I could in high school and then earned my BFA degree in college (studio art/painting).

After graduating, I married my first husband, and began working as a graphic artist for a local bank. I tried to do a little painting when I could find time. My husand decided to start a home building company in 1980. We had two children, and when they were almost two and four, I left my graphics job to stay home. For the next couple of years, I did the bookkeeping for my husband’s business, painted and did freelance graphics work when the kids napped and at night after they went to bed. That lasted a couple of years until it became necessary to get my real estate license so I could help my husband’s business by selling his homes. Ironically, the week that I was waiting for the results of my real estate test, Denise Burns, founder of Plein Air Painters of America, was in our town to teach an oil painting workshop, which I attended. She really inspired me and encouraged me to pursue my art (the painting I did in that workshop still hangs in my studio next to my easel).

I passed the real estate test and, reluctantly, ended up having to put my art career on hold. With two small children, the demands and time commitment of a real estate career and still doing the bookkeeping for the home building business, there was no time for art (other than drawing architectural renderings to advertise the homes we built). Three years later, we divorced.

Throughout my time in real estate, I never lost sight of the goal of returning to my art career someday. I always considered myself an artist first, and real estate was just temporary.

In late 1991 I married my husband Don, with whose love and support I was able to return to my art career. By this time I was doing architectural illustrations for several home builders and little pen and ink drawings (sometimes with watercolor added) of people’s homes to give as closing gifts. I also did note cards printed from my pen and ink drawings of homes. Soon, other realtors started ordering my drawings and cards for their own clients. Eventually I got to the point that I was earning almost as much from the “house portraits” as I was from selling real estate.

I started painting again a couple of years later. When Don saw my paintings and how happy it made me to be painting, he encouraged me to let go of the real estate career and get back to creating my art full time. We remodeled our basement into a small classroom where I taught art classes for children. I painted, and continued doing the house portraits, renderings and graphic work. Eventually, my art took over the spare bedroom, the basement, the office and then the dining room. At that point, in 1996, we bought a small building in our little downtown area and remodeled it to house my studio, a large classroom, a frame shop and a gallery…and I let my real estate license go. That freed up my days for art and my evenings and weekends for family time. Each year we analyzed which areas of my art business were profitable for the amount of time and money being spent, and reviewed and set new goals. I closed the gallery after four years to spend more time producing my own work, and eventually stopped doing commercial framing for the same reason. Next, I let go of the renderings and graphics work, and started scaling back on the house portraits (which were all deadline oriented and not as enjoyable as painting) so I could concentrate just on painting.

Also in 1996, the same year we opened the downtown studio, I began taking one painting workshop a year to help improve my painting skills. The first one was with Tom Browning in 1996. In 1999, my first plein air workshop was with Kevin Macpherson in Bermuda…AND I FOUND MY PASSION. I went on to study with Kevin several more times as well as Kenn Backhaus, John Cosby, Kim English and Scott Christensen. Other than traveling to workshops, I stayed pretty close to home until my children graduated from high school. I began entering juried shows and competitions, first locally, then regionally, and finally nationally. Being accepted into several, and winning a few awards, brought attention from some gallery owners and resulted in representation by three of the four galleries who currently represent me. Although I’d been a full time artist (which included painting too) for about ten years, my goal was to be a full time painter. I made that transition about seven years ago.These days, I try to paint during the day and do my marketing in the afternoons and evenings. Some weeks I’ll set aside a couple of days just for marketing. I spend probably about as much time on the business side of art as I do actually producing art.

What is your role as president of the American Impressionist Society?

I’m still very much in the learning process since I’ve only been in this position since the end of January of this year. Communication and coordination best describe the biggest roles I have at this point, and working with the board, the founders and the officers. The first priority was to get to work on our 14th Annual National Juried Exhibition with our Show Chair, Suzanne Morris, who had already been working hard on the show for a few weeks. The show will be held at M Gallery in Charleston SC in October. I’ve worked on things like writing the show prospectus, arranging for the workshop in conjunction with the show, communicating with our web designer, recruiting volunteers to help with various aspects of the show, updating the AIS Facebook page as needed, and writing communication for the membership. Now that the online entry system for the national show is active, I’m fielding questions from members and helping however I can. I’m actively seeking ideas and suggestions for new opportunities and ways to serve our membership so we can continue to build on what is already a great organization. We already have one exciting thing in the works…but as nothing is finalized yet, you’ll have to stay tuned for more information as it progresses.

There are so many art groups today that differentiate themselves according to medium, subject matter, style, region of the country, or even gender…what are your feelings about that?

There really are a lot of them. I think that many of these groups do give artists a place where they feel their art fits in (style, medium, subject matter), as well as opportunities to meet other artists, network, paint together, take part in workshops and, often, group exhibitions. The main thing I’ve done is research what they offer and decide which of the groups fit my needs, my goals and my work. My style of painting is more impressionistic and I do a lot of plein air painting, so I’ve done well with AIS and plein air groups, such as Laguna Plein Air Painters and Plein Air Artists Colorado, as opposed to other groups who, for example, favor tighter realism. There are not a lot of artists in the area where I live, but through one fairly new group, the Missouri Valley Impressionist Society, I’ve been able to connect with many artists who live in about a three hour radius of me. Through MVIS I can participate in paint outs and exhibits closer to home that I otherwise would not have known about. I paint landscapes, but I also do portraits and figurative pieces, so I’ve been encouraged to join the Portrait Society of America, which I’m now seriously considering. In my experience, there are a lot of benefits to be gained from being a member of a group or groups.

Several contemporary art movements seem to have a pretty fuzzy definition as to what fits into their “movement”…What is your definition of Impressionism? Is it merely surface appearance, intention, a philosophy…or is there more to it?

Impressionism is more about spontaneously capturing a moment in time, an “impression” of the subject, by carefully observing and quickly rendering the effects of light on the subject, the colors, the atmosphere, movement. Impressionist paintings are representational with visible brushstrokes but without a great amount of detail (think plein air paintings as the most obvious example). Tightly rendered pieces with a lot of detail and smooth surfaces wouldn’t fit into that definition. The American Impressionist Society, Inc. defines American Impressionism as “the concern for light on form, color, and brushstrokes. It allows equal latitude between these attributes, and recognizes not a single definitive element, but several factors – including high key light and hue, visual breakdown of detail, concern for contemporary life, and cultivation of direct and spontaneous approaches to a subject”.

What proportion of your work is done en plein air?

Probably about 70 to 75%.

What qualifies as a plein air painting?

There are so many different opinions on this subject. To me, if the majority of the piece is painted outdoors, on locatoin, from direct observation, from life, it qualifies as plein air. Now “majority” can mean different things to different people. I think some touch ups in the studio are permissible for it to still be considered plein air. I have a couple of pieces I did in Zion National Park that need tweeking, but probably 85-90% of these pieces were completed on location. Just because I will finish them in the studio, the overwhelming majority of each was plein air. In my opinion, they will still qualify as plein air. I’ve had to paint from inside my car during rain and thunderstorms, and because I’m painting it from life, on location, from the actual observation of the scene in front of me, I consider that plein air as well.

What are the major problems encountered when translating a field study to a large studio painting?

The major problem is to translate that freshness and immediacy that you achieve in the field on to the canvas in the studio…it’s very, very difficult. So much of that freshness is achieved because the time is limited in the field…the conditions are changing so rapidly that to capture the scene, you have to paint quickly and more intuitively. In the studio, there are no time constraints. The light isn’t going away. The shadows aren’t moving. There is much more time to think about what you’re doing and that in itself takes away from that original feel of the field study. I no longer try to make the studio pieces be an enlarged ‘copy’ of the field studies. Instead I use the studies as color reference and inspiration. It frees me up to play with composition, color, mood, etc, in the larger paintings and is much more fun.

What advice do you have for a first-time plein air painter?

Keep it simple! Pack as lightly and as compact as you can when it comes to your gear. There are a lot of options out there for equipment. Be sure to have a hat with a good brim, sunscreen, bug spray and plenty of water to drink. Avoid wearing bright colors when you paint outdoors as they will reflect onto your canvas and skew the color in your painting. Keep your canvas and palette out of the direct sunlight…even if it means having your subject behind you. Keep your compositions simple. Block in your shadows first and commit to them. Avoid ‘chasing the light’ (changing your painting as the light changes). Work quickly.

What are your artistic goals for 2013?

To stay organized, to successfully serve and lead AIS and find new opportunities for our members, to produce another 20 paintings for the solo exhibition this fall with historical works by artist Abby Williams Hill, to have a successful National Juried Exhibition for Plein Air Artists Colorado (I serve on the PAAC board and am the show chair this year), be more consistent with my blog, to get out and paint on location locally as much as possible, and to create a new body of seascape paintings from the plein air studies and reference photos from a recent trip to California. I will be traveling and painting for a month this fall as well.

Thanks Debra for your time, for your active participation in so many art organizations…and for your boundless energy. From your resume, it’s pretty obvious…you’re not done yet.

Diane Massey Dunbar Revisited

To my mind, no one paints glass better than Dianne Massey Dunbar. Her depiction of things transparent is very carefully observed and yet painted with such intuitive confidence, dexterity, boldness, clarity, and excitement that one just marvels at her ability.

I first interviewed Dunbar in August 2012, and at that time only revealed half of the interview. Now, with a few additional questions, here is the remainder of that amazing interview.

Read Part I of Dunbar’s interview here

What would be your definition of art?

To me, art in its broadest sense includes music, dancing, acting, photography, painting, writing, and the like. It is a personal expression of oneself that generally involves creativity and honesty and an audience. It almost always requires a degree of skill. It is also, invariably, the end result of a process.

Narrowing the definition to drawing and painting, to me art is the creation of an image personal to the artist that is intended as a visual dialogue with an audience. When I stop and contemplate art, it is easy to think of eloquent paintings that have been carefully designed and executed. However, I have seen many rough drawings by children that have deeply touched me. So, I guess I would say that if a painting or drawing reasonably incorporates the principles of drawing and design and craftsmanship, and further inspires in me as a viewer a sense of awe or excitement, interest, beauty, or involvement…and if it is intended to be art, I would call it art.

Are you saying then that you believe art is really in the eye of the beholder?

In my opinion, everyone is entitled to his or her own definition of art. For me personally, I agree and disagree with the statement “art is in the eye of the beholder”. That phrase seems to infer our personal likes and dislikes. I do believe that our tastes influence what we enjoy in the way of art, if we are attracted to a particular painting, whether we like thick or thin paint, still life or landscapes, realism or abstract. It is our emotional response to a painting.

Can there be art if it doesn’t communicate with an audience, in other words, if it can’t be understood?

In order to answer this, I need to define “understood”. One might not recognize the objects in a drawing or painting, or fully understand what the artist was trying to accomplish or communicate, but that does not mean it’s not art. For example, a person that is not versed in biblical stories might not understand religious art. However, I think most people would agree that there are numerous examples of wonderful religious art. Another example is prehistoric art. I may not understand the symbols, recognize the figures or the animals, but I can still appreciate the lines and design. And, many people do not enjoy abstract art but once again that does not discredit it. Understanding a painting has absolutely nothing to do with the subject matter, and everything to do with the visual elements and execution of the painting. So, even if I do not understand the subject matter, I can still appreciate the shapes, the drawing, the lines, the texture, the design, and in that way it still communicates with me.

To be art it must be able to be understood from a purely rational point of view and be organized to create a visual statement. If a drawing or painting is so disorganized that I am unable to understand the visual elements, then I do not think it meets any definition of art. All art, including abstract art, must have drawing, shapes, and values. One can study the painting to see if it is balanced, and if the values and composition are working. Lacking any visual organization so that there are no shapes, values or drawing, well, it would be difficult to call it art.

Do you consider the process of painting more important than the result?

I think they are rather inseparable. If the result is a finished painting, you can’t have the result without a process of some sort. And, at some point in time the process of painting ends in a finished piece. I will say that for me, the process greatly influences the result, which includes all my preparation before I begin a painting. I will also admit that for me the most important part of the actual painting is the beginning, because it will set the tone for the remainder of the painting.

No, what I mean is…Do you consider the act of painting itself…one’s personal joy in applying paint, experimenting and creating…more important than the physical result?

I wish I could answer yes to that question because it would be so freeing to let go of the end product and simply enjoy the process of painting. Also, if creating art was merely the act of painting with no regard for the outcome there would not be the inherent fear of failure or the discomfort when we are outside our comfort zone. However, being a professional artist is a career, a business, and so one must consider the end result as well. I think that there needs to be a balance between the creative process and respect for the end result. If it is all about the act of painting, experimenting and being creative, which incidentally can be quite frustrating on occasion, then we are on a journey that does not go anywhere. If it’s all about the end result, I think over time we become bored, don’t take risks, become too comfortable and our art grows stale and predictable. So, I think the process and the end result are inseparable, and I can only hope that as I paint I am aware of and can appreciate the joy and frustration of creating.

Where does creativity come from and how can it be nurtured?

I believe that creativity is a gift from God. I also believe we all have some degree of creativity and that creativity is not reserved for artists, musicians, actors, writers and the like. Everyone from plumbers to lawyers, teachers to advertisers and to builders, all encounter problems that require creativity to resolve. Mulling it over, it seems to me that creativity is often the result of problem solving, curiosity, need, a willingness to explore and a desire to be creative. Creativity also requires imagination and an open mind. To nurture creativity, we need to emphasize and value exploration, give others enough tools and knowledge to be able to explore different options, and offer problems that require imagination and problem solving.

You said in our first interview that you love to play with paint…to smear it, scrape it, splatter and flick it…using all manner of tools. Were you a pretty creative child?

Probably yes. I was rarely interested in playing with dolls or dress up although I loved stuffed animals. What I really liked to do was make things. So I played with Lincoln Logs and Tinkertoys. I had a small tool set with a hammer and saw, and I would use wood and nails to build things. One Christmas I was given a wood burning set so that I could decorate the things I made. I liked crayons. I started drawing at the age of six, and started art lessons and oil painting at age seven. I also use to write…primarily poetry.

How does your work reflect your personality?

First off, I think I am somewhat sentimental, so much of my work is derived from my life experiences. It is my impression that no matter who we are or what we do, most of life is lived in the ordinary, not in the extraordinary. I think there is something special, maybe even sacred, about the ordinary stuff of life. I want to somehow honor those things we use or images we see in our daily lives that often go unnoticed. I appreciate the ketchup bottle I pulled out of the refrigerator nearly every day when my sons were young. I can find beautiful colors in simple jars. There are surprising greens in a stack of French fries. The world is full of wonderful shapes and color everywhere, even where least expected. I hope that people can see the world a little differently as a result of my painting.

How does one find their individuality as an artist?

I would say finding individuality is a process. Where you begin will likely be very different from where your journey of art ultimately leads you. I also believe that individuality is a result of passion, excitement, exploration, risk taking, failing, succeeding, practicing, and honesty. Paint the subject matter that excites or interests you. Play with paint. Splash it, brush it, knife it, smear it, and make puddles. Try different surfaces because I am learning that they too make a difference. Be creative because after all, we are artists. Some paintings won’t succeed but will boost you to the next painting. Eventually you will have enough paintings behind you, that instead of you finding your individuality, I imagine your individuality will find you.

You use a very extensive palette of colors. How do you manage to maintain control of the color harmony in your paintings?

What advice do you have for a young artist/painter?

Making art is a journey and not a sprint. There are no real road maps beyond practicing and attempting to master the basic skills involved. It requires a great deal of passion, commitment, dedication, practice, and courage. Along the way there are wonderful highs and times of utter frustration. Being an artist is not at all what one envisions being an artist should look like. I believe it is about 85% work, 10% fun, and 5% inspiration. Also, I am not at all sure that we choose being artists. I rather think art chooses us. I cannot imagine not painting.

Primarily, I would suggest that you practice drawing. Drawing is absolutely essential to whatever type of art you eventually choose to do. Painting is nothing more or less than the completion of shapes. You need shapes to put value and color on. Those shapes need to be drawn, whether you do abstract art or representational art. I cannot stress the value of drawing enough. Also, if you are having problems with a painting, check your values. I have found that color can be rather forgiving, and that a problem with a painting is more often a value issue. Experiment, play, scrape, and learn what paint does (and doesn’t) do.

Find a mentor; an artist that is better than you, whose opinion you trust and who is willing to critique your work and offer suggestions along the way. Avoid asking others what they think of a painting or project, for opinions are as varied as the weather…and often not helpful. So, get a mentor/teacher to help with this process. Learn from your failures. Take those to your mentor as well.

Don’t be too quick to approach galleries. Everyone wants to be represented by a gallery and many young artists make it their goal to be invited into galleries. Instead, your goal should be to focus on your art and make it as outstanding as possible.

Lastly, keep some of your early work. I have a painting up in my studio from several years ago. When you get discouraged, and you will at times, look at that painting and spend a minute being proud of your progress.

Finally, be aware and prepared for the fact that painting is expensive and for most of us it takes time and practice to get to the point of earning any money.

Dancing with the angels – Part 2

There are lots of words for it…”in the grove”, “singularly focused”, “in tune”, “wired in”, “centered”, “on a roll”, and “in the moment”. Some have described it as “going with the flow”.

It is said of Michelangelo, that while he worked on the painting for the Sistine Chapel, he became so focused on the job at hand that he went for days without eating or sleeping until he almost passed out.

That does seem to express the sentiments of some of our twelve artists as they discuss painting “in the zone”…not that any of them have actually passed out…but you get the idea.

I am pleased once again to bring you six more very accomplished artists who will continue our discussion of painting “in the zone”…is it real, what’s it like, how do you get there, and what’s the result? When it happens, it’s like “dancing with the angels”.

Thanks to this week’s participants, as we present Part 2.

Karen Blackwood:

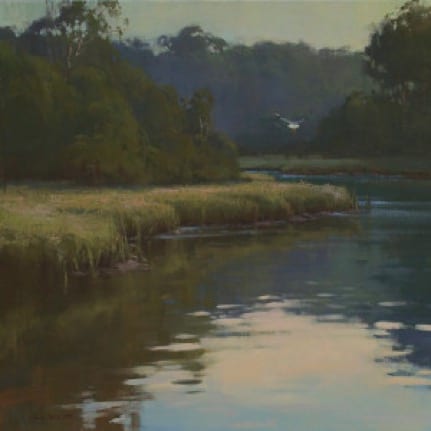

Karen Blackwood:Classically trained, Karen Blackwood initially painted portraits and figurative works before the landscape became her constant muse. While her work gravitates toward the light and atmosphere in the landscape, her artistic pursuit is to convey an emotional response to the solitary beauty of nature and to achieve that perfect state of being that sometimes comes from painting it.. She is represented by Susan Powell in Madison, CT. She’s a member of Oil Painters of America and the Society of American Marine Artists.

Roger Dale Brown:

Roger Dale Brown:Roger believes that studying and painting from life is essential to being a good artist. He spends hours painting on location to enhance his ability to see the nuances of a scene, a day, or an object. He considers this one of the elements necessary to create a successful painting both on location and in the studio. Roger captures the emotion of the scene, by drawing on his knowledge and his dedication to art. He promotes art education in many ways, believing that passing along information is an obligation to generations of new artists.

John Cook:

John Cook:From still life to portraits, landscapes to architecture…and his native-Texas western imagery, nothing is too small or too large for John to attempt as is demonstrated in his diverse range of subject matter. Trips to London, Paris, Bruges, Venice, Rome, Florence, Portofino, St.Marguerite, San Francisco, and New York have inspired many of Cook’s paintings. In 2012, Cook’s 11th annual one-man show was held at the Southwest Gallery in Dallas.

Kathleen Dunphy:

Kathleen Dunphy:Kathleen’s rapid success in the competitive art world was predicted when American Artist Magazine recognized her as one of the TopTen Emerging Artists in 1998. In the ensuing years, she has earned an impressive and growing reputation with galleries and collectors. A Signature Member of several important art organizations, most recently she has been honored with Signature Membership in the prestigious Plein Air Painters of America. She is one of those rare people who have true passion, dedication, and a gift for transposing nature’s beauty to the canvas.

Daniel Gerhartz:

Daniel Gerhartz:The powerful and evocative beauty of Gerhartz’s paintings embrace a range of subjects, most prominently the female figure in either a pastoral setting or an intimate interior. He is at his best with subjects from everyday life, genre subjects, sacred-idyllic landscapes or figures in quiet repose, meditation or contemplative isolation. “My desire as an artist is that the images I paint would point to the Creator, and not to me, the conveyor. J.S. Bach said it well as he signed his work, ‘Soli Deo Gloria’, To God alone is the glory”.

James Gurney:

James Gurney:Gurney is the author and illustrator of the New York Times bestselling Dinotopia book series. Solo exhibitions of his artwork have been presented at the Smithsonian Institution, the Norman Rockwell Museum, and the Norton Museum of Art. He’s recently been named a “Grand Master” by Spectrum Fantastic Arts and a “Living Master” by the Art Renewal Center. His most recent book, Color and Light: A Guide for the Realist Painter (2010) was Amazon’s #1 bestselling book on painting for over 52 weeks and is based on his daily blog: gurneyjourney.blogspot.com

We’ve all heard the phrase “in the zone”, what does that mean to you?

Blackwood:“The object, which is back of every true work of art, is the attainment of a state of being, a state of high functioning, a more than ordinary moment of existence.” –

Robert Henri. “In the zone” is that perfect state of being I strive to be in while painting, It’s a state of letting the spirit within lead, working from the subconscious mind. Every movement and thought flows effortlessly.

Brown:Being in the “zone” to me means being in a more visceral region of my mind. Being made in God’s image, humans are inherently creative in one thing or another. When an artist creates, we go to a place in our subconscious that taps into the knowledge intuitively, and our emotions instinctively.

Cook:Things are “clicking” when I’m painting productively. Not that it is an easy process, but I know somehow what looks “right”, when the preceding brush stroke, or knife application is placed. I “explain” to myself often audibly, what temperature the next color should be, and what pigment, or mixture is wanted, or what correction is needed in drawing, and so on…Of course the drawing must be correct, and the composition must be worth continuing. Color, whether intense or muted, or purposefully unbalanced, should remain harmonious. The balance of simple patterns vs the complicated textures are becoming obvious to me, due to many paths down that road for the design to be “on”. Must mention correct values. I could go on…I shall…Then the treatment of edges seems to fall in place. I can seem to understand which need to be “lost”, and those that need to show straightness and obvious clarity. I do have much more fun watching an oil sketch fall in place without thinking much, something with a real flair happening quickly…within 45 minutes to an hour and a half.

Dunphy:Being in the zone means being able to paint without tremendous effort, much like hitting my stride when I’m running or nordic skiing. All extraneous thoughts from other parts of my life turn off and I’m solely focused on the task at hand. It’s finding that rhythm when my mind, body, and creative energy are all in sync.

Gerhartz:When the conditions are right and I am accurately translating what my eyes see in terms of the abstract nature of light, shadow, shape, edge and color.

Gurney:Having my conscious mind take the back seat, and letting intuition take over.

If you believe in such a phenomenon, what techniques do you use to get there?

Blackwood:To help me get “in the zone” or at the least, a higher level of focus, I try to approach my subject with great feeling. Taking the time to contemplate before brush touches canvas helps me to let go and paint from a more intuitive place, allowing the information to “flow” through me. In the studio, listening to music and looking through books of a master artist’s work can stir my soul and subconscious, which allows flow to happen. I have been known to listen to the same CD to an insanely repetitive degree. If it works for a particular piece I’m working on, I tend to want to keep that mood throughout.

Brown:It is important that I have an atmosphere that is conducive to painting. In my studio I have surrounded myself with inspirational things and music. This comfortable space helps me remove the “world” from my mind, so I can be more sensitive to the scene I am painting. Also, I problem solve; I imagine being in the scene, or on location again; I assign words to describe the scene; and finally I visualize the finished painting. By approaching a painting this way, it helps me bridge the two elements of painting, the science of painting and the intuitive aspect of painting. When I have a solid image in my mind, I can start painting. All of this helps de-clutter and prepare my mind to paint so it’s easier to sink into that nice warm comfortable place…and create…

Cook:Don’t know how to “get there”. I can’t force anything to get there. In fact last year, because of some very stressful conditions, I was definitely out of the zone for a least six months. I struggled with drawing especially, and consequently painting anything worth showing anyone for that period…well, I won’t linger on this. Tough year.

Dunphy: It’s easiest for me to get in the zone when I’m outside plein air painting. It seems like that direct communion with my subject matter helps me to more easily ignore that background chatter of non-art-related thoughts. I still can get in the zone in the studio but it happens with more effort. I’ve found that certain music helps set the tone – classical baroque music, Italian opera arias, and most especially Gregorian chants.

Gerhartz:Putting myself in the position to be successful, (working from life, distractions minimized, enough rest, approach the subject humbly, and squint!)

Gurney:Ironically, I’ve got to think consciously to get to the intuitive state, and just practice a lot.

When in the “zone”, are you more conscious and aware of what you’re doing…or less so?

Blackwood:When I’m in the “zone”, I am more highly in tune to what I’m painting but less self-conscious of my process. It’s a more intuitive state where the painting seems to paint itself. I lose all sense of time, at least until my husband or daughter calls out for food!

Brown:Even though my space is important at the beginning of a painting, once I am in the “zone” I am less conscious of my surrounding, or of time, and more in tune with my creative process. I would say I am less conscious when in the “zone”. Since I worked through the foundational decisions and possible problems with my painting early on, the decisions and process of painting are easier. This doesn’t mean it’s a “walk in the park” for there can still be struggles, and sometimes I still have to wrestle that thing down, but I am less likely to get frustrated and angry. I stay calm and the painting proceeds at a nice pace and rhythm.

Cook:Definitely aware of what I’m doing, as described in the first answer, but not laboring mentally or emotionally.

Dunphy:Both – I’m more aware of the idea and feeling that I’m painting and less aware of the technical aspect of it.

Gerhartz:Not necessarily aware of it. More aware when I am not in it.

Gurney:I’m inside the painting, not thinking of my immediate surroundings.

Are your best ideas and work a result of being “zoned in” or does it make any difference?

Blackwood:I am personally more fulfilled when I am “zoned in”. It is invigorating, joyous and feels like a state of being more fully awake. Because the subconscious is flowing more freely, I think there is a deeper level revealed in the work for those able to read it, making it more successful for me.

Brown:All of my planned ideas and crucial decisions about a painting come prior to the “zone”. Once the decisions are made, and I have a clear image of my painting, I am free to de-clutter my mind, and go into the “zone”. The advantage of this process for me, is when I am in the “zone”, my right brain is in control. This opens up the opportunity for some fantastic ideas to arise during the painting. I can realize them and take advantage of these opportunities.

Cook:Can’t answer that my best ideas come “in the zone”, but my best canvases definitely do.

Dunphy:Yes, by far my best work comes when I’m in the zone. It causes a conflict for me because I can only be in the zone when I don’t have the distraction of other people around, even other artist friends. I enjoy the camaraderie of painting with others and need that human interaction, but I end up having to view those paintings days more as “mental health” days instead of times when I get serious work done.

Gerhartz:I believe all artist work is best when focus is concentrated and precise. I believe my best works have almost painted themselves.

Gurney:The two modes switch back and forth for best results, like two different creative characters: The idea man and the refiner.

Is it possible for a “zoned in” person to produce work beyond their normal ability or level of understanding?

Blackwood:Being “in the zone” is an active, high state of functioning that can propel me to another level. Provided I have acquired the necessary skills, the excitement brought on by a challenge above my current level of understanding awakens my spirit and allows me to reach the higher state within that my conscious self sometimes blocks.

Brown:For me, the only way this whole process works is to study and build my understanding of the fundamentals of painting, understanding what I see and my ability to see as an artist. I have to train myself to see the subtleties of a scene and to understand perspective, atmosphere, quality of light, shade, value and edge. You can’t paint what you don’t know. We are given talent, but passion is the driving force that will develop it. Without putting in the work the emotional part of art has nothing to draw from. Since being in the zone is being more visceral, I don’t think I can paint beyond my ability, but it does make it easier to work from the knowledge that I have collected over the years and it makes me more intuitive with my decisions and not over think and second guess myself.

Cook:Any piece that exceeds my normal ability is a gift from God. Should that happen, I believe I would continue doing even greater things, with a dedicated work ethic. Love this! There are some pieces in the past that stand out as hard to “match the magic”. I wouldn’t continue if I thought it might not happen again.

Dunphy:Without a doubt. I call those works gifts that are given to me in order to let me know I’m on the right track and encourage me to keep going.

Gerhartz:Yes

Gurney:To me, intuition is conscious understanding made automatic. Rarely do I get major leaps of intuition that take me beyond my conscious awareness of solutions.

When “in the zone”, are you aware of it?

Blackwood:I think on some level I am aware that I am “in the zone”. Everything feels so right. When I’m out of it, I still have that lingering “high” that makes me look forward to painting again. It is an addiction, isn’t it?

Brown:I am aware I can go to the “zone”, but I don’t always know that I am there, until someone or something interrupts me.

Cook:Definitely aware when I’m “in it”, however, being in it one day doesn’t necessarily carry over to the next session. Hate this!

Dunphy:Not right away. Usually some time will have passed where I realize I’m in a great rhythm and not struggling so much. Then I try not to think about it to much in order not to jinx myself out of it!

Gerhartz:Not always, the more I think about being “in the zone” the more I can be assured I am not in it.

Gurney:Yes, and I try to abet the mood by means of music or sound effects.

For those that have not read Part 1, I invite you to do so. It also features six elite artists: Kenn Backhaus, Joni Falk, David Gray, Marc Hanson, C.W. Mundy, and Romona Youngquist. It’s also very good. Just click here and continue reading. Thanks.

Dancing with the angels – Part 1

When Facebook friend, John (Skeets) Richards, suggested I do a blog addressing the issue of whether or not artists are in a “zone” when they paint their best, I thought it was a good topic to pursue. I personally don’t think in those terms, I’m just focused on doing the best painting I can. I will acknowledge that once in a great while some of my paintings have been created so effortlessly and quickly that they seem to have painted themselves…but most of the time it is just tough, down and dirty, hard work…with all the ensuing frustrations.

I guess I never thought of those effortless paintings as having been done while “in the zone”, but maybe that’s a suitable explanation. After considering the opinions expressed below, it’s very possible I’m “in the zone” more than I realize. Having professional artists address the issue will cast light on the subject. It’s hard to deny that something really special can happen when we’re in the creative mode…often unexpectantly. I call it “dancing with the angels”.

I’m honored to have such an elite group of artists address this issue. Here are this weeks participants:

Kenn Backhaus:After an award winning career as a commercial designer and illustrator, Kenn decided in 1984 to devote more time to his passion for painting and his love of the outdoors. He found that capturing true color, value, atmosphere and the mood of a subject was best done on location or through direct observation. Winner of many awards and a featured artist in a 13-part PBS television program “Passport & Palette”, Kenn is a Master Signature Member of the Oil Painters of America and the American Impressionist Society.

Kenn Backhaus:After an award winning career as a commercial designer and illustrator, Kenn decided in 1984 to devote more time to his passion for painting and his love of the outdoors. He found that capturing true color, value, atmosphere and the mood of a subject was best done on location or through direct observation. Winner of many awards and a featured artist in a 13-part PBS television program “Passport & Palette”, Kenn is a Master Signature Member of the Oil Painters of America and the American Impressionist Society.

Joni Falk: Joni has lived in Phoenix, AZ since 1960. She has been featured in several magazines and books, and is a popular instructor at the Scottsdale Artist School. Her work is included in the permanent collections of The Cheyenne Old West Museum, The Booth Museum, and The Desert Caballeros Museum. She’s represented by Legacy Galleries, Settlers West…and has participated shows at The National Museum of Wildlife Art and the Cowboy Museum in Oklahoma.

Joni Falk: Joni has lived in Phoenix, AZ since 1960. She has been featured in several magazines and books, and is a popular instructor at the Scottsdale Artist School. Her work is included in the permanent collections of The Cheyenne Old West Museum, The Booth Museum, and The Desert Caballeros Museum. She’s represented by Legacy Galleries, Settlers West…and has participated shows at The National Museum of Wildlife Art and the Cowboy Museum in Oklahoma.

David Gray:An award winning artist, David has made a career of pursuing a pure and relevant art form which has its roots in the Classical Tradition. The resulting paintings reveal a personal and contemporary expression of beauty and order while giving a clear nod to the Old Masters. David’s works have been collected throughout the United States and abroad since 1997.

David Gray:An award winning artist, David has made a career of pursuing a pure and relevant art form which has its roots in the Classical Tradition. The resulting paintings reveal a personal and contemporary expression of beauty and order while giving a clear nod to the Old Masters. David’s works have been collected throughout the United States and abroad since 1997.

Marc Hanson:A Signature Member of OPA and winner of the OPA Bronze Medal for oil painting in the 2011 National Exhibition. He was awarded both Artist’ Choice and Best of Show at the 2012 Door County Plein Air Festival. His work can be seen at Addison Art Gallery, R.S. Hanna Gallery, Gallery 1261, Elizabeth Pollie Fine Art, and the Mary Williams Gallery.

Marc Hanson:A Signature Member of OPA and winner of the OPA Bronze Medal for oil painting in the 2011 National Exhibition. He was awarded both Artist’ Choice and Best of Show at the 2012 Door County Plein Air Festival. His work can be seen at Addison Art Gallery, R.S. Hanna Gallery, Gallery 1261, Elizabeth Pollie Fine Art, and the Mary Williams Gallery.

Charles Warren Mundy:Worked as a sports illustrator for several years. In the early 1990’s he took on the challenge of painting in a more impressionistic style, going out of doors and painting “en plein air” and “from life”. Now a noted American Impressionist, he is a Master Signature Member of OPA. Most recently, 2007, he was awarded Master Status in The American Impressionist Society. He is also a Signature Member of The American Society of Marine Artists.

Charles Warren Mundy:Worked as a sports illustrator for several years. In the early 1990’s he took on the challenge of painting in a more impressionistic style, going out of doors and painting “en plein air” and “from life”. Now a noted American Impressionist, he is a Master Signature Member of OPA. Most recently, 2007, he was awarded Master Status in The American Impressionist Society. He is also a Signature Member of The American Society of Marine Artists.

Romona Youngquist:Self taught with nature as her classroom and the great masters her teachers, Romona knew at age four that painting would be her calling. Today you’ll find her paintings as far away as Germany, London, and downtown Manhattan. Her works have been published in the premier art magazines including Southwest Art, American Art Collector, and Art Talk.

Romona Youngquist:Self taught with nature as her classroom and the great masters her teachers, Romona knew at age four that painting would be her calling. Today you’ll find her paintings as far away as Germany, London, and downtown Manhattan. Her works have been published in the premier art magazines including Southwest Art, American Art Collector, and Art Talk.

Backhaus: Being in the zone is like a well-oiled machine, you are performing without hesitation, no distractions, and can push yourself and you respond, The challenges that are present or come up during the painting process become solved. The traditional sound principal and foundations guide your skills that you have acquired over the years. Confidence directs the eye and the hand. Everything within you and around you is in harmony.

“In the zone” for me, means my painting seems to almost paint itself…a sense of confidence and satisfaction as the painting progresses.

Gray: To me it means that space in time when everything you do is “right”. In these moments it seems like you can do just about anything. And if you do make a mistake it is corrected with ease and on the spot. It’s a time when everything you’ve learned is working for you. Your background, natural skills, education, and years of hard work are all coming out on the canvas and it’s glorious. You trust yourself implicity and all of your second guessing goes out the window. Ir’s a great place to be.

Hanson: My earliest memories of being an ‘artist’, were while sitting at my parents kitchen table with a newsprint drawing tablet and some pencils and crayons, making action drawings of tanks, soldiers and airplanes at war. Man, was I “in the zone” then. In a place of total imaginative, creative thought, where the question from my mom…”Marc, are you listening to me???”, didn’t even make a sound wave in that zoned world that I was in while the airplanes and helicopters flew over head, while the tanks rumbled across the impossible terrain, and while so many army men became ‘X’s and tanks went up in clouds of red and yellow flames. That is what being in the zone means to me. Being totally absorbed in the act of creative activity, in a heightened state of awareness. Being so absorbed by the painting activity, that nothing else around me has meaning, and time evaporates. It’s letting your conscious mind go to where it needs to go to achieve complete concentration on the task at hand.

Mundy: “In the zone” is a term used by an artist to describe being subconsciously carried along in the painting, making one creative move after another. You may not be aware of being in the zone. The painting experience has mesmerized the artist.

Youngquist: Being “in the zone” is like having a wonderful massage in which you’re conscious but asleep at the same time. It’s the place I want to be. It’s where I reach my optimal creativity and production and where I have the most fun.

Backhaus: I don’t think you can control when you get into the zone. I feel it happens on its own from one’s focus and enthusiasm of the project.

Falk: Regarding the phenomenon of “in the zone”, I think it is just that…if there were a technique to get there, I sure would like to know what it is…???

Gray: I don’t believe you can force it or make it occur. It just happens sometimes. It comes as a result of years of discipline. I consider that I am highly skilled and have worked very, very hard for many years to develop my craft. I can paint or draw something very well on demand. But that doesn’t mean I’m in the zone. Usually I have to keep my wits about me the entire day of painting and the littlest thing can throw me off. Still I have learned how to fight through and create effectively. Only once in a blue moon do I ever feel like I’m truly in the zone.

Hanson: It’s easiest for me to find myself “in the zone” when outside on location, painting ‘en plein air’. Almost every time that I paint outside, I’m there, in the zone. I think that’s partly why I feel that is the most honest place for me to be painting. Having the time constraint of plein air painting, and the lack of any outside interference, except for the occasional passerby, makes it the ideal situation fo me to find myself in that zone.

In the studio, to help me move into that place of concentration, I choose music to listen to that will help me find that zone once I get a painting going. That changes from day to day, and according to where I am in the painting. At first I like music that is…loud and upbeat. Music that sort of shakes the rafters. Then as I am developing the painting, I turn to music that is softer and less intrusive, that allows me to concentrate. Sometimes I need to turn it off completely and have a silent work zone to zone out in.

Mundy: Problem solving should be the process before ever beginning the painting. The left hemisphere of the brain, the analytical side, is the problem solver. Preparedness in getting everything ready is hugely important. It’s like a surgeon who has everything on the table and ready to go. I also have found in the last six months, that I have more opportunity to get into the zone if I have no music, no distractions. Having the excitement to create, to take on the challenge of a new painting, is a key ingredient and a wonderful start!

Youngquist: The best way for me to get there is to be constantly painting. It’s like a snowball effect and the more I paint the more everything around me disappears (not good for housework). And the ideas just keep coming.

Falk: As far as being more conscious and aware what I’m doing or less so…I definitely think I am aware I’m in the zone in that the painting seems to be flowing and coming together more easily – and with more confidence..

Gray: I think I’m just as conscious. It’s just that all my decisions seem to be “right”. All my marks are spot on. I’m still very cognizant.

Hanson: Yes, I’m totally conscious of what I’m doing when in the zone. I paint without thinking about what I’m doing, but on a conscious level. My experience, training, skills, and desires as an artist become one fluid movement when in this place. Like I mentioned above, it’s a heightened state of awareness that I find myself in when there. Being in the zone is very similar to being in a meditative state. I tried meditation as part of a yoga class I was taking once. I realized that when I’m painting…and in the zone…I’m consistently in a meditative place, so the meditation class was kind of pointless for me.

Mundy: It’s a combination of both being conscious of what you’re doing, and less conscious. But if you really “let go”, it can lean toward being unaware of what you’re doing. There’s a connective interplay between both knowing and not knowing.

Youngquist: I’m less conscious and intuition kicks in. And that’s where the fun and passion happens.

Backhaus: Yes, definitely my better works come from being in the zone.

Falk: I think some of my best paintings were done while “in the zone”, and I look back on them and wonder “how I did that”.

Gray: I think for me there is a slight difference. In general I would say my best work has been done while “zoned in”, but not always. I’ve done some paintings I’m very proud of that have been a fight every step of the way.

Hanson: This is a difficult place to be if you have interruptions by phones, other people, or errands to run for the day. My best work comes when I’m lucky enough to be able to find that level of concentration. Not because there’s anything metaphysical about it, simply because I’m concentrating and keeping a clear path open as I paint along. With too much interruption, I loose the ability to go deeply within myself and my creative thoughts. It makes sense that a painting wouldn’t get the full store of what I feel and have to offer it if I’m not there.

Mundy: Based on my own results, the best paintings can be painted either in the zone or not in the zone. Nevertheless, for creative explorations, every endeavor and experience is different.

Youngquist: Heck ya.

Backhaus: Yes.

Falk: I do think it is possible to produce work beyond normal ability or understanding…it’s as if that feeling of “self-doubt’ disappears.

Gray: I think so. I’m not sure I’ve been there, but I believe it can happen. My process is so controlled that I am very rarely surprised by the result. “Happy accidents” just don’t happen with me. Though highly skilled and a good teacher of my craft, I still don’t consider myself a “Master”. I’m not sure I’ve done a work that completely transcends my earthbound limitations. But I believe it can happen. I’ve heard of these kinds of experiences happening to people working in other art forms as well…musicians, or actors, for example.

Hanson: I’d prefer to say that it’s ‘more possible’ to create the work that you’re capable of making, if you are able to concentrate at the level that being in the zone brings to you and your painting.

Mundy: It is absolutely possible for a “zoned in” person to produce work beyond their normal ability. Retrospective thinking will prove it out.

Youngquist: I think you still only paint to the level of your knowledge, but happy accidents happen. If only I can remember how I did it.

Backhaus: As I mentioned earlier, for me I may be performing for a time period before I realize that I am in the zone. Believe me, you will know it when your’re there. The results of your efforts should reveal it.

Falk: When I am “in the zone” I am definitely aware of it – it’s that special feeling I wish I could experience more often.

Gray: Yes, I think I am.

Hanson: I think this one was pretty much answered in question #3.

Mundy: In most cases, I am not conscious of being “in the zone” although on the other hand, several times, I think that I have made the realization that I’m in the zone while “in the zone”.

Youngquist: It’s the same thing that happens when getting a massage. Your aware but at the same time not….(using linseed oil instead of lavender).