Landscape and wildlife painters today and throughout history have been responsible for awareness and change as explorers, documentarians, and conservationists. For instance, the idea of our National Parks is largely credited to artists and authors. Our paintings today are just as important as those of the The Hudson River school artists who first shared western views with their world. I recently had an opportunity to share experiences and dialogue surrounding the Oyster Reef Restoration in Apalachicola Bay, Florida.

The Forgotten Coast, a 130 mile stretch of the northwest Florida coastline, begins in Mexico Beach and continues through Port Saint Joe, Carrabelle to St. Mark’s. Little did I know when I began painting the area almost ten years ago, that I could eventually become part of something so worthwhile and spread such an important message through my work. With twists and turns and a vast array of eco-systems, there is such a variety of subjects to paint. I have painted the area on dozens of trips and produced nearly 1000 sketches. At some point I found myself navigating more and more toward Apalachicola Bay and Eastpoint, areas which are known for the best oysters and shrimp you’ll ever eat. Everyone from the New York Times to Field and Stream thinks so! Sure, I enjoyed eating them too, but due to recent environmental and economic strains that have impacted oyster reproduction, I became and more interested in documenting the crises and the plight of Apalachicola Bay.

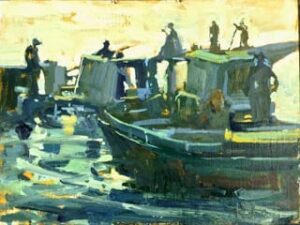

Buildings, boats, and people connected to the industry have been in my paintings. Many of the structures no longer stand, boats have literally sunk before my eyes, and the men and women no longer work many of the depleted oyster beds.

by Lori Putnam

11×14

by Lori Putnam

8×16

“Still Standing,” is ironically NOT still standing.

In 2013, I painted “Re-Seeding Care Line,” (private collection), documenting the early morning re-shelling process. For as far as the eye could see, boats lined up to take on a front loader bucket of used shells. Each load was then dumped in a specified location in order to help with the oyster bed restoration. Oyster beds are fragile. They have survived, however, quite well until recent years. Even the area’s hurricanes have typically been just a part of the circle of life. But expanding growth in cities north of the area lead to fresh water being captured and diverted for residential and commercial use well before it had a chance to flow naturally into Florida’s pristine bays. The lack of freshwater flows from the Apalachicola, Chattahoochee, and Flint River system has upset the salinity balance. Either there is too much salt, allowing sea creatures and habitat to destroy the beds, or the water is released in a way that does not allow for it to flow naturally and slowly, gathering much-needed nutrients along its way. It then floods the bay, shocking the oysters with fresh water which reduces the balance needed to maintain healthy oyster bars. Replacing oyster cultch by local oystermen each spring for the past four years has been successful, but there is still much work to be done in this area.

by Lori Putnam

12×16

Another depiction of the people and their labor, “Eastpoint Blues,” (private collection), was painted during a demonstration from sketches and photographs during the Portrait Society of America Conference in 2014.

Getting an Early Start,” (available), shows the oyster houses and ice house in the small town of Apalachicola as workers begin their day of taking in and processing oysters and shrimp.

These are just a few of the pieces which lead to an Artist-in-Residence program in March of this year. I was invited to get a more personal look at the people whose lives have been most effected by the declining availability of oysters there.

by Lori Putnam

20×24

The highlight of the program was a day I spent on an oyster boat with Eugene and Delene Millender-King. According to Eugene, he had his wife once filled 5 or 6, 60-pound bags of oysters an hour. Today they are lucky if the get 2-4 in an entire day. Delene sits on the side of the boat, measuring each oyster one by one as Eugene works to tong with the huge, scissors-like tools. Oysters measuring less than 3” are likely male. Those are not to be harvested. Once oysters reach a certain size, they become female.

Illegal catch is another factor that has contributed to the oyster population. Following the closure of such industries as the St. Joe Paper Company, Arizona Chemical and decreased jobs in construction, the slowed economy meant more people began looking for ways to feed their families. Many turned to the fishing industry. Oystering is generational. Many of the oystermen and women’s parents and grand parents were also fishermen. But many younger generation harvesters do not have the same respect for the bays that their ancestors have, resulting in over harvesting. Now, inspections are required. This Spring, every oyster was checked again for size, and there are hefty fines for anyone caught breaking the law.

by Lori Putnam

8×10

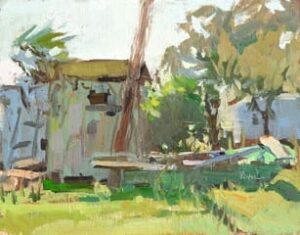

“His Granny’s House,” (available), barely standing along the shore in Eastpoint.

Small, 3-4″ sketches on oil paper were made to provide resource materials needed for larger studio pieces to come. I found out later that one of these small sketches was the home of Delene’s brother and a small blue boat with very high bow was built by her father. The high bow was engineered at Delene’s request, following a near-fatal day when unexpected storms and high seas nearly capsized their boat.

by Lori Putnam

8×10

In “New Measures, (private collection), officers and the youth Conservation Corp of the Forgotten Coast are checking bags of oysters and retagging them once they have passed inspection. (The CCFC is part of Franklin’s Promise Coalition, Joe Taylor, Executive Director. A comprehensive youth development program for young adults 18-25 years of age (veterans up to 29, and summer internships for ages beginning at 16 years old) it provides participants with job training, academic programming, leadership skills, and additional support through a strategy of service that conserves, protects and improves the environment, as well as community resilience. This initiative will accomplish an array of specific habitat restoration projects throughout the region such as invasive species removal, living shoreline installation, oyster reef restoration, water quality monitoring, and pine savanna restoration.)

Processing facilities in the area, such as 13-Mile Seafood (named for its location 13-miles along the coastline from Apalachicola), were once bustling with workers washing, bagging, and preparing oysters for transport to restaurants and markets. Over 60% of oysters consumed throughout the southeast (and points beyond) were once trucked from this region. According to Tommy Ward, this company handled more than 250, 60-pound bags a day prior to 2012. Now they average just 25.

by Lori Putnam

8×10

This sketch, “13-Mile Brand,” (on loan), is the outside of the facility and is just one of many plein air sketches I have made there over the years.

Proposals and solutions are a constant topic. From visitors to restaurant owners; from fishermen to scientists; from engineers to congressmen; many people are working to assist in recovering a healthy balance for this most significant resource. Each entity which whom I spoke had a slightly different take on the issues. Some optimistic; some not so much. The one thing all agreed on is that this is the worst it has ever been. Without fail, everyone I spoke with thanks me for what I am doing, as an artist, to help bring awareness. When I returned to Tennessee to work on studio pieces, I heard their voices and replayed their stories in my mind. In early May, I returned to Eastpoint to present my findings through work produced over the years, during the residency, and in the studio. You could feel a bit of tension in the air during the discussion which followed my presentation. Over and above all of that was the sense of community and togetherness. It was a difficult thing to present knowing that Delene, Eugene and other oystermen were there. We have become friends and I feel close to their families and fellow fishermen.

by Lori Putnam

24×28

by Lori Putnam

18×24

by Lori Putnam

8×10

The studio painting, “A Stark Reality,” (on loan), has stimulated much discussion while on exhibit at the Eastpoint Visitor’s Center. It, along with other sketches and “Raw Bar,” (private collection), are on loan for an extended period to help continue moving conversations forward. The sketch “Tongin’ and Cullin’” (private collection), was painted while actually sitting on the bow of the boat, was presented as a gift to the Kings as thanks being so amazingly genuine and open during my time on the boat.

The following week, more conservation efforts were also brought to the front of the Forgotten Coast community and visitors who had come for their annual plein air event. I was part of a panel discussion with fellow artists Mary Erickson and John P. Lasater, IV which was moderated by Mr. Jean Stern, Director of the Irvine Museum in California. Mary Erickson offered information from her residency surrounding the ecology and balance of one of the world’s most significant estuaries at St. Joseph Bay State Buffer Preserve, also located in the Forgotten Coast area. Mary’s interest in birds is not only a part of her attraction to this region, it is a part of her life.

by Mary Erickson

She purchased the neighboring property to her North Carolina home in 2006, giving her close to 40 acres to oversee. “That fall, an adjacent 130 acres of woods was “harvested” –cut, bulldozed and burned,” states Erickson. “As I sat on the hill overlooking the charred remains, I worried where all of the winter and migrating birds would go. I put up feeders all along the fence line to help the birds that came back to find their food and protective tree cover gone. That was the beginning of an all-consuming work in progress! We now have bird feeders scattered throughout the pastures, trails and woods. We are continually adding nesting boxes, and mow selectively, to give adequate cover and nesting grounds for many different species. We have two year-round ponds and one seasonal wetland, in addition to birdbaths, to provide a bountiful water source. In addition to almost 70 “sight” identified birds, we have deer, raccoon, rabbit, bobcat, possum and fox. Feral cats are trapped and turned in to the local animal rescue. We use pesticides and fertilizer only as a last resort, and then very sparingly, on the property.”

by Mary Erickson

Erickson’s property, High Ridge Gardens, is listed on the North Carolina Birding Trail, and is slated to be left as an ongoing artist retreat and bird sanctuary. In addition to Mary’s home, the property holds a 1350 square foot studio and a four bedroom, three bath guest house available to artists, photographers, birders & musicians, and is very affordable for small groups. High Ridge is about 1 hour from Charlotte, NC. Her description says it all, “With canopied country lanes, meandering meadows of green and gold, whisper quiet creeks, and gently rolling hills, the rural villages of Marshville and Peachland boast more fence posts and horses than people. Tucked snuggly away and centrally between interstate highways, it continues to defy time and the temptation to “improve”. Artists come from far and wide to settle, sketch the barns, paint the fields, capture the magic of this area lost in time. There is no traffic, no big box stores, no noise. Horses have the right of way here. I want to leave High Ridge so that people can come here and stay, enjoy morning coffee on the deck of the guest house, watch deer feed along the pond and listen to the song of the birds. Mornings in spring host a cacophony of bird song, and on summer nights we listen to the chorus of frogs, crickets and cicadas. Our dream is to leave the property as an ongoing artists’ retreat and bird sanctuary, long after we need to be here, so that others can enjoy its serene beauty.” “Our talent is a gift, what we do with it is our gift in return” – Mary Erickson

by Mary Erickson

by John P. Lasater, IV

John Lasater, from Arkansas, shared his Artist-in-Residence experience for his local Illinois River Watershed (of Arkansas and Oklahoma). According to Lasater, “I had a few aims including painting, art education, and exploration, all in the name of building awareness and appreciation.

As an exploration junkie I had a great time finding and painting much of the disregarded vistas and waterways, and as a gift to the area, I built a Google map of my favorite spots. It’s an area of raw beauty, and I continue to encourage its residents to be stewards of it, and to take a part in shaping it.”

“This is a view from our yard in Arkansas, and I’ve never been able to do it justice. After about 5 or 6 outdoor painting sessions on it, I think I’ve expressed one of my most sincere pieces to date. Obviously, it’s not a “magical” time of day. It’s pretty subjectless. The light seemed “silver” to me so I adjusted my palette to make that come across.

Someday I hope to be able to bring many people here to study and enjoy the natural beauty of Arkansas. See more art by John P. Lasater by clicking here

by John P. Lasater IV

Additional articles and videos to give you a taste of what is happening in the oyster industry:

- Apalachicola Bay Oyster Industry Facing Uncertain Future

- The Disappearing Apalachicola Oyster: Florida’s Fight to Save Its Prized Delicacy

- Oyster Farming “True Treasures of Apalachicola Bay”

- The Heritage of Eastpoint – Oyster Harvesting

- A. L. “Unk” Quick, Oysterman

- Oystermen and Researchers Fighting for Apalachicola Bay: In the Grass, On the Reef

Images courtesy of the artists.

Marsha Savage says

Lori, I thoroughly enjoyed the article. I have always believed as an artist we bring much awareness to the land and seas around us and all that depend on them. I appreciate you and other artists that have the ability to speak on behalf of the land and the people and all that depend on the conservation of it. The work you show in the article is inspiring. Thanks again!