It is said that everybody has a story, and every life is interesting. I totally agree with that, it’s just that some people have lives that are more interesting than others, and in the process accomplish great things. That’s the way I feel about Melissa Hefferlin, Daud and Timur Akhriev. I call them the Ak-REE-ev family. I really have Suzie Baker to thank for suggesting this interview. I am so thankful that she did because communicating with Melissa via email, and with Timur on the phone, I have gained great admiration for this family. They are incredibly talented and versatile with a captivating and interesting story. All speak multiple languages and each have made significant contributions to this world through their art. Daud and son, Timur, are Russian, while wife and step-mom, Melissa, is American. Timur is not necessarily in favor of me calling Melissa his step-mom as he is adamant that he has two moms…and Melissa is one of them. They all live in Chattanooga, TN but spend a significant part of each year in Spain. At the 25th Annual Oil Painters of America National Show, held earlier this year at Southwest Gallery in Dallas, Daud (rhymes with cloud) was awarded the Silver Medal, just a tick away from the top prize of $30000, for his painting, “Harbor Conversations”. Meanwhile, son Timur received an Award of Excellence for his painting, “Youth”. This interview has been broken into two parts because of the extensive and thorough responses. This week is about their background and training. Next week we get a little more personal. You’re going to love this. Here is their story:

Melissa Hefferlin

You’re right. At the age of twenty I went to study at the Russian Academy of Fine Art (you have the official name correct) in “ Leningrad” when it was still the Communist Soviet Union. I was not only the only American woman, I was the only American to study there during Communist times. Only J.M. Whistler studied there before I did, while his father built railways for the last Tsar, if I have the facts correct. I was studying painting at Otis/Parsons Los Angeles, and was rather unhappy with the emphasis on being fashionable. I met a Russian scientist who advised me that the Russians had the best art school in the world for Realism. At that time, maybe you remember 1980’s and 1990’s, we didn’t have many American destinations for the intensive study of Realism. I had to take the Russian man’s word for it, because there was no internet, there was no information on art schools in the Soviet Block, there were no ways to independently investigate the possibility. But I have always loved adventure, so I quit Otis/Parsons, sold my VW bus, and bought a ticket to Soviet Russia. (How I got a visa is a whole different story, and we don’t have time for it here.) When I arrived, the person who was supposed to meet and guide me had left the country, so a nice family my parents knew took me in. (When I was a pre-teenager, we were sent to Communist Russia as an exchange family for two years as a peace initiative on the part of President Carter. This program was run by the Academies of Science of both countries.) It’s a great piece of luck that I had no understanding of the difficulty of being accepted to the Russian Academy, because if I had known I might have given up. Being ignorant, I called all my host’s friends and found someone who knew someone in the Academy of Art, and got an interview appointment. After confusion and a very intimidating interview with some fifteen Academics (painters-educators who have received the highest educational level of the Academy of Arts of the country) in the mahogany board room, I was allowed to stay by an executive decision of the department head. They were mostly dumbstruck on how I got there, I think, and were willing to honor my gumption.

How long were you a student at the academy; how were you received, and what were you specifically hoping to learn?

I stayed for a year, like a year abroad. When I had my credits analyzed by an educational board in NYC, in that one year I had accumulated double the amount of studio hours required for a BFA in an American university. I was received with great curiosity, and mostly gracious welcome. I was the only American student out of 800, so I felt sometimes like an exotic creature in the zoo. When I arrived I was grossly underprepared, and performed far below the average student of my year. Most of my classmates had gone to art school for children for eight years, art high school for four years, and often art college for a BFA before coming to the Academy for six more years. Many were in their mid-thirties. I worked hard enough to nearly destroy my health. By the time I left, and with the encouragement and mentorship of both fellow students and professors, I was performing solidly with the middle of the class. That proved to have been one of the most useful periods of my life.

Your resume is quite impressive; what three things are you most proud of as an artist?

Thank you. You are very kind. Surely that my young self had the luck and determination to attend the Russian Academy during a time period when stellar painters were still teaching. The painters who mentored us were of a caliber and of a time period which simply does not exist there today. These men (and they were all men) had painted through the siege of Leningrad, had survived Stalin, had studied with fantastic masters themselves….This would be the event I’m most grateful for. No matter what else happens, my soul expanded and I received guidance from astonishing painters and that knowledge and experience will always be MINE. I met my future husband there. I maintain friendships of great worth to me twenty five years later. That’s number one. Secondly that I am privileged to make a living at a thing I love. I am aware of people who work labor to survive in profoundly unpleasant or repetitious or dangerous jobs (no matter how grateful they may be to have employment) and I am humbly grateful for the honor to be paid for my passion in visual arts. It’s a huge thing, yes? And on a humorous note, one of my favorite awards I was unable to accept. I entered a painting of heifers into the Kentucky State Fair. I’ve always loved State Fairs, and have an affection for the farmers of Tennessee and Kentucky, and even more for their bovines. I received a phone call that my cows were up for Grand Prize, but the judges felt they needed to inform me that the purchase prize money was 1/5 of the value of the piece. With regret I declined, but was pleased as punch with my heifers being selected. I also particularly enjoyed the honor at the Pastel Society annual juried show of the Salmagundi Award. I love that historic art club.

Daud Akhriev

I was born in Kazakhstan because we were deported (so was my entire nationality) in 1944 to Kazakhstan from Ingushetia. After graduating from art college in the South of Russia, in the Caucasus, I then was accepted in the Leningrad Academy of Art, which is now the St. Petersburg Academy of Art (The Repin Institute). There in art school in Leningrad, I met Melissa where she was studying in Mylnikov studio with a friend of mine. When the school year ended she invited me to America and we made a life together. That was the summer of 1991.

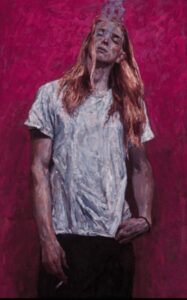

Oil Painters of America 2016 National)

At the age of eight you were singled out by the Soviet educational system to receive special training in art; what did that training involve, when and for how long were you a student?

The program I entered was officially a four year program. We were given tests, because the applicants were many. If you were accepted it was a 3-hour program after regular school, three times per week. Two months of the summer we were taught in plein air. I studied under Nikolai Vassiliovich Zhukov, who was at that time one of the top tier teachers for young students in the world, and much awarded. Even though our country was so closed by Communism, Zhukov had visitors from educational delegations from Japan, England, France, India, and others, to study his method of teaching the young people. We entered competitions all over the world and won medals in youth categories. Once, in that program, I won a medal with a personal letter from Indira Gandhi, and a set of Dutch paints. All the other kids wanted my Dutch paints. Legally the program was for children between 8 – 14. Before that, at first I was too young to enter the school because I was seven, but when the educators saw my drawings they allowed me to come illegally with the other students and attend the courses until the year I was accepted officially. In my memory, when I think about the best art schools I’ve known, I prefer that school even to the Academy, because the atmosphere was at least equal to the Academy. I preferred it because it was in an Art Nouveau mansion, with absolutely the best of the best architecture, the most fantastic teachers with a well-structured system for building a base in drawing, painting, composition, sculpture and art history. It was in Ordzhinikidze, which is now Vladikavkaz.

What are the significant differences between Russian academic training and what is typically found in the United States?

Russia has a wider range of exercises for training yourself to draw over and over and over until drawing from your head is effortless. I have never heard in a Western school where a drawing or painting will take 40 – 50 days, which our drawings at the Academy regularly did. We were expected to hone gesture drawing on our own time. We had models six days a week, five hours a day, plus evening drawing group three times per week. On top of that, all our art history teachers were well-known art historians from the Hermitage or Russian Museum, they were published authors on particular periods. So when you combine the theoretical education with teachers of that level (like having Andrew Wyeth teach you egg tempera), and you have lots of such teachers, it makes for a strong education. Also, we had the museums all free for us to enter and copy from Old Masters, with professors from the restoration department overseeing our copies. All the teachers focused on how to compose within any given shape…to use the space. And also for example in painting, when you have a painting of a model, the school was careful to give you assignments where the model was against a green background, then a black one, then a red one, in a situation with a lot of pattern, etc. Then they made it more complicated by putting two models, or three, which had to be proportional and harmonious. And, this is very different, the critiques were really critiques—-not designed to encourage students who are “ clients” of the school. The critiques were designed to eliminate your weaknesses, and they were ruthless in the best possible way. And while we lived humbly, we were given a stipend, a room in the dorm and art materials, so we could really focus on the work. Today, of course, that has changed a great deal.

Timur Akhriev

What was your childhood like in Russia?

My childhood in Russia was interesting for a lack of a better term. In 1991 we escaped war and moved from Vladikavkaz which is in the southern part of Russia. ( NOT VLADIVOSTOK!!!!!! AS MANY PEOPLE MISTAKE.) St Petersburg is up north. I was about 7 or 8 at the time and had to miss the whole year of school, but eventually did attend a public school for about two years before switching to art school. I think I had an easier time adjusting to the change as very young person than my family did.

As I told you on the phone, we kind of ended up being refugees within our own country and I think it made a very large impact on me.I think one might grow a thicker skin in situations like that, which sometimes can be a minus.

You were in art school from 1995-2002, eventually immigrating to America in 2002 to be with your father who came in 1990, and with, Melissa, your stepmother. While in school, with whom did you live, and how did you support yourself?

I entered an art school in 1995 and graduated in 2002, the same year I moved to US to live with my parents. My father moved to US in 1990 with my mom Melissa (if you need for some technical reason to call her step-mom you are welcome to do so, but I always considered her my Mother. I have two.) While I was attending school I lived in one apartment with my grandma Marietta, my two aunts Fatima and Diba and my sister Danna (it was packed). Because I was very young I didn’t have to support myself, most of my family had jobs and we had support of mom and dad who were already living in US. But if you are interested, I made my first sale when I was sixteen, it was a still life with a saddle and porcelain bull.

Like your father, at a young age you too began art studies in St Petersburg, and later in Florence; please tell us what your training was like.

The training in Russia was absolutely great and awesome. We had a seven year program which trained you from basic perspective to multi-figurative compositions. In the first year of the program we had to draw a cube on a surface with drapery to understand the perspective. After that we moved to sphere and cone and had to do it several times. In addition to that we had to paint still lifes in watercolor with pitchers and fruit, or cast iron skillets to understand different patterns, or something transparent filled with water. The reason we could only paint watercolor for the first three years is because this media teaches you precision. A mistake in watercolor is hard to fix, so eventually you have to learn to be precise in your approach to application and drawing. In addition to regularly scheduled classes, we had homework assignments, which included figure sketching, cityscape sketches, and multi-figurative composition sketches for larger projects throughout a year. Every summer we had a “Summer Practice” in a huge garden that our school had, it was not manicured, but was very natural, beautiful, and green. If you were between 6th and 9th grade you were assigned a still life in that garden for about three hours a day and after that we had to go paint cityscapes. If you were between 10th and 12th grades you had to paint a live model in the garden for about the same amount of time and also after that you had to paint cityscapes. At end of the 9th grade we had to pass exams to continue studying at this school, which included still life in oil, drawing of the mask and multi figurative composition. From 10th to 12th grades we had more advanced assignments such as nude model with different color backgrounds and live models with still life’s or some sort of arrangement.

Florence Academy was a great school too. I’ve learned many things from them as well, they are very disciplined and and have their own approach to drawing and painting and I still use certain technical aspects that they taught me. One of the great things about the Florence as a place was that I could go anywhere in Tuscany and paint one of the most beautiful landscapes in the world. So combined with academy training and painting city or landscapes on the weekends, I kind of raised my level, and I think for the first time I saw my paintings starting to look more advanced and professional.

Marsha Savage says

Wonderful interview. I can’t wait to hear the rest. It is inspiring and really shows how dedicated they were… something many Americans have no idea about.

John pototschnik says

Thanks, Marsha. I found Melissa, Daud, and Timur delightful, extremely interesting, and wonderful to work with in putting the interview together. I suspect Part 2 will follow next week, but I don’t know for sure.

Barbara Fox says

Beautiful interview! Thank you for introducing these passionate, lovely people.

john pototschnik says

Glad you liked it, Barbara.