Not unlike the vast majority of OPA members, I displayed a talent in drawing and painting at a very young age. My earliest training comprised drawing from life, learning perspective, shading (value studies) and composition. All of which were based on fundamental principles necessary for artists who wish to depict the natural world. For almost four decades I painted the natural world in Alla Prima methods, however in the desire to broaden my knowledge and artistic skills, I enrolled at age 40 in a BFA program at the State University of New York. Once I was immersed into the studio program, I recognized that few of my fellow students had any comprehensive art training. More surprising was the realization that there were also art professors who lacked drawing skills and a fundamental ability in drawing from life. Painting, Printmaking, Sculpture, and Photography Departments echoed a familiar instructional refrain, “Be free to express yourself.” Instruction stressed conception, not perception. I modified my work in order to comply with their modern vision for art but the BFA program only served to raise more questions. Namely why Modernism elicited such a strong emotion against academic training and the premise on which this new art movement was inspired.

The answers were forthcoming when I became a Graduate Art History student. The culmination of this two year research program resulted in my thesis. It was entitled “CHILDREN’S ART; an Analysis its Relation to Creative Expression within Twentieth-Century Art”. The following is merely a broad over-view, but it may help to shed light on the logic behind Modern Art and its various movements.

During the centuries preceding the Impressionist Movement young apprentices developed their artistic talents in guilds under the rigorous instruction of a Master Artisan. Academies opened and attracted greater numbers of artistically talented people, primarily men. This mass enrollment resulted in a highly competitive and politically influenced atmosphere.The societal climate during the mid 19th Century was evolving from a two-class system based on monarchies. Those in the church and wealthy landowners comprised the upper class while the masses of the working class poor made up the lower class. The 1848 revolution began with the overthrow of the French monarchy. This eventually resulted in a mindset that the art academies were corrupt and complicit with the suppression of the lower class. Thus the art academies lacked relevance in this new socio- political environment. Furthermore, with the rise of the Industrial Revolution people could earn a living wage and pursue opportunities previously unavailable to them. These opportunities meant that those who desired to pursue a career in the visual arts could do so and without the influence or restrictions of the state, church, or an art academy.

Many factors have provided the stimulus for the various Modern Art Movements. These factors included African Tribal Art, Freud and Jungian Psychoanalysis, Asian Culture, Revolutions, and Wars. For the purpose of this article my focus sheds light on children’s art, specifically from age two until the reasoning age of seven. At the start of the 20th Europe and America, educators were curious and explored the developmental processes of children, specifically why children identify with making marks vertically; due to their upright physical condition. Also why the circle is the first enclosed form they make; it represents a wide range of objects from Century in their environment, i.e. Sun, faces, and bodies.

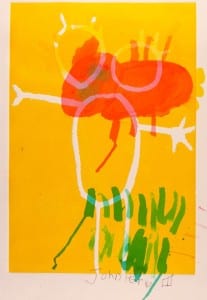

The Modernists were not intent on copying children’s art. Rather to adopt many of the insights that child psychologists – such as Jean Piaget, a Swiss psychologist and philosopher – had uncovered in their research. Paul Klee looked to his three year old son’s drawings to influence his paintings. Jean Dubuffet felt it was abnormal for an artist to devote too much time in studying an object for the sole purpose of representing that object in its exact proportions. Studying the drawings of children, he found inspiration for his own art. Mark Rothko taught children’s art classes and found inspiration in their primitive markings, which influenced his own paintings. However, there were much larger catalysts influencing these artists in adopting a child-like style, and those catalysts were the first and second World Wars. Having witnessed firsthand the horrors of these World Wars, early Century Modernists used their art as a protest platform. 20th Not only did their art reflect the horrors of war, but they also drew upon childlike innocence, reminding the human race of the innocence which remains deeply within us all.

Want to know more about me? Please visit

susanbudash.com

How do I get better? I acknowledge an area I am weak in and study that area. It is important for me to schedule time to do this. I am easily distracted with life situations and business. I also take advantage of an opportunity when it arises. I keep a drawing pad with me so I can draw anytime. Studying is not limited to painting. Drawing helps improve hand–eye coordination, seeing value and developing an intuitive response to my subject.

How do I get better? I acknowledge an area I am weak in and study that area. It is important for me to schedule time to do this. I am easily distracted with life situations and business. I also take advantage of an opportunity when it arises. I keep a drawing pad with me so I can draw anytime. Studying is not limited to painting. Drawing helps improve hand–eye coordination, seeing value and developing an intuitive response to my subject. I decide how many on location or from life study paintings I want to paint that year. I schedule the time as much as possible but many times it is spur of the moment. Realize that every painting is not started with the idea that it is going to be a finished masterpiece. Most of the time I paint on location to study. I can read, study, take workshops every month, but if I don’t put theory to the test I will not grow. Most times I paint from life with the intention of studying a specific problem area or theory, not to create a masterpiece. Paint with a plan!

I decide how many on location or from life study paintings I want to paint that year. I schedule the time as much as possible but many times it is spur of the moment. Realize that every painting is not started with the idea that it is going to be a finished masterpiece. Most of the time I paint on location to study. I can read, study, take workshops every month, but if I don’t put theory to the test I will not grow. Most times I paint from life with the intention of studying a specific problem area or theory, not to create a masterpiece. Paint with a plan! Before I touch my canvas, I try to see the subject in its’ simplest form or as an abstract. Then I mentally build the scene back up and visualize the end result of my painting. I have discovered when I visualize the end result of my painting, the likely hood of succeeding increases.

Before I touch my canvas, I try to see the subject in its’ simplest form or as an abstract. Then I mentally build the scene back up and visualize the end result of my painting. I have discovered when I visualize the end result of my painting, the likely hood of succeeding increases. It is very important to become a student of art, to develop a critical eye. I have collected a library of art books, I look at magazines and visit museums whenever possible to study. Having a group to critique each other’s work regularly is also very helpful to start understanding what makes a good painting. To know a good painting when you see one, you also have to see the mistakes. The old masters, contemporary masters and our piers make mistakes. It’s just as important to see what they did wrong as it is to see what they did right.

It is very important to become a student of art, to develop a critical eye. I have collected a library of art books, I look at magazines and visit museums whenever possible to study. Having a group to critique each other’s work regularly is also very helpful to start understanding what makes a good painting. To know a good painting when you see one, you also have to see the mistakes. The old masters, contemporary masters and our piers make mistakes. It’s just as important to see what they did wrong as it is to see what they did right. I put a lot of importance on being a well-rounded artist. My passion is landscape panting. I love the outdoors and the beauty of nature. But, I also like other subjects and I know that one of the ways for me to grow is to be diverse in what I paint. I also venture to try new techniques, new mediums and tools and I even make tools and equipment to help in certain situations. At the end of the day I always bring something new back to my art.

I put a lot of importance on being a well-rounded artist. My passion is landscape panting. I love the outdoors and the beauty of nature. But, I also like other subjects and I know that one of the ways for me to grow is to be diverse in what I paint. I also venture to try new techniques, new mediums and tools and I even make tools and equipment to help in certain situations. At the end of the day I always bring something new back to my art. There are a number of different types of frames. The Hudson River School has an ornamental and gilded appearance. The Whistler style has fewer lines. Both of these styles are price prohibitive. Currently many people use the Plein Air style which has closed corners, is simple and reasonable. They are Asian or Canadian made.

There are a number of different types of frames. The Hudson River School has an ornamental and gilded appearance. The Whistler style has fewer lines. Both of these styles are price prohibitive. Currently many people use the Plein Air style which has closed corners, is simple and reasonable. They are Asian or Canadian made. Spots on liners may be removed using white bread, rolled up or a sketching eraser.

Spots on liners may be removed using white bread, rolled up or a sketching eraser.