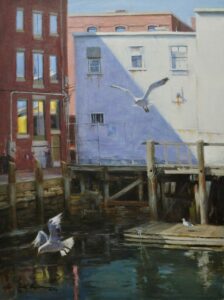

In my opinion, observation skills and a visual interest in how something looks with light on it is what is most important. A personal example might be that I love to paint boats and water, but I know very little about boats except which end is the bow and which is the stern. From observing, I am aware that the shape of a lobster boat is different that that of Shrimp boat, or an Oyster boat, etc. I have a passion for painting boats because I like the shapes and the way they look in water. That is only one example of many subjects that artist choose to paint that do not require expert knowledge to do reasonable representations of them.

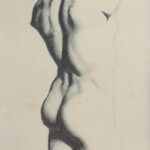

By the same token, one can do a very reasonable rendition of the human form without ever taking an anatomy class…..of course anatomy study does not hurt, and I certainly would never discourage any one from studying the human anatomy. Any knowledge gained can be helpful…..particularly in checking one’s self if there is an issue, but it is not an absolute requirement. Artists have done a very good job over the years without studying anatomy, if their observation skills are strong. I believe the artist should be interpreting their observations and not simply copying them. Copying is for cameras. Another problem with relying on knowledge instead of observation is, if one is observing the subject, and something looks vague, fuzzy or not clear as in a shadow area….one should paint that image as they see it, and not use their intellectual knowledge of the subject and make it a clear statement. It will not look appropriate to that particular situation. Example….something dark in shadow value, if made to light and sharp will jump out of the shadow. Another foreseeable problem with using knowledge of subject rather than observation is that one could fall into a formula, and everything starts looking the same. If one is using anatomy knowledge for example. All figures should not be exactly alike.

One could compile a never ending list of subjects that this might apply to. By no means am I implying that one should not learn all one can about the subject they choose to paint….if that is one’s interest. This is only my opinion on this subject, and does not necessarily reflect any universal opinion or idea on the subject. I do find this an interesting topic, and I do believe strong observation skills trump knowledge of a subject as it relates to painting.

Again thanks for listening to my Cajun ramblings.

Education

Learning To Draw Like An Angel (Michelangelo)

The Florence Academy Of Art

I don’t know what to expect at the academy. Following the 19th-century French Academy which developed neo-classicism, Daniel sets an agenda for new students like me. Immediately I am assigned to draw an exact copy of a finely defined pencil drawing of a man wearing a hood. He very much resembles the Florentine poet Dante.

I draw exact dimensions and values of white through scales of gray to black with a HB (hard black) drawing pencil. Each stroke must be crisp by keeping my pencil sharpened with a mat knife, pushing from the tip of the lead, back along the shaft and up into the wood. I shave away until I have a long lead with a pinpoint-thin tip so I can make sharp, distinct marks of lead.

I never press the pencil into the paper to make a darker mark. Instead, I stroke one line next to another on a smooth white paper. Each mark falls crisply in place. The more I stroke, the darker the definition of a shadow becomes. On the other hand, when I have gone too dark, I erase and begin again with a freshly sharpened pencil. I love to draw and am so engrossed that hours pass without my noticing the time. I lay a string as a plumb line vertically to line up the head. I use the plumb line, as well, to establish the tip of the shoulder in relation to the chin line. And this measuring of angles and spaces continues throughout the drawing. By the time the drawing is completed, I have sharpened my pencil 100 times.

Main Drawing Room

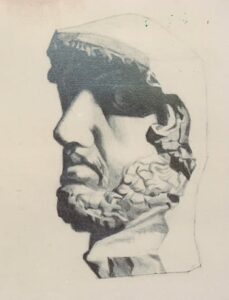

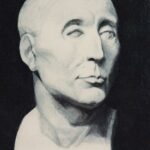

Finally, I graduate to the main drawing room where classical plaster casts stand on pedestals against black velvet drapes. The room is painted black and black curtains cover side windows. The daylight streams through north skylights onto the statues. No unnecessary reflected light interferes with our tasks of drawing exact replicas of the statues.

I stand back eight feet from a statue, alongside six other draftsmen who stare at their individual statues. The room is quiet, although some students are playing their tape recorders with ear plugs. I listen to silence as I mount on my easel next to my statue an 18”x24” sheet of heavy charcoal paper. I stare at a lovely Grecian female in classic pose and wonder if I will ever be able to replicate her beauty of lines and shadows.

Working With Charcoal

That is when I begin to use charcoal in ways I had never known. For one thing, I am instructed to buy Fusam NITRAM, a vine charcoal made in France of the highest consistency. It comes in hard and soft. Fine charcoal which is difficult to find in the United States can make the lightest delicate gray marks with feather touch. It also can be sharpened with a mat knife from tip to shaft.

With the finely sharpened charcoal I stand back to get a sense of how wide and tall and how dark and light my drawing should be to duplicate the original. I hold my plumb line in order to eyeball a point on the statue. Then I move the line horizontally so I can mark the same spot on the paper. I stare at that point as I carefully walk forward to the paper and touch the spot with my charcoal.

I continue to eyeball the plumb line horizontally and to establish the vertical angles and alignment of body parts to give the figure a natural and classic stance that is not stilted. The hardest part of replicating a statue is to place the shapes and strength of shadows. I begin to recognize geometric shapes which crop up in any composition or design.

To help me see values without reflections of incidental light, I use a black mirror (vanity mirrors are usually backed with silver) to establish the exact values of half lights and shadows. Correct lighting indicates that the figure may turn toward and away from the light source and into the shadows. It is like dancing, writing poetry, and singing in symphonic variations. I hold the black mirror at an angle where I can see the statue juxtaposed next to my drawing in progress which I compare to the plaster cast. The mirror cuts out glare and I then adjust the art to match the true values in nature.

In all, the drawings are precise and time-consuming. As a result, I am learning to see infinite detail of light, shadow, line, and pose. I draw with great care. This eyeballing, sharpening of charcoal and walk goes on every morning. My drawing and touch on the paper improves during the three months I live in Florence. Quickly, I correct my major flaw of drawing objects and people larger than they are in proportion to other objects.

When I am not drawing, I wander into museums and churches to converse with Michelangelo, Ghirlandaio, Leonardo da Vinci, Fra Angelico, Masaccio, and Pontormo. These great Florentine draftsmen guide my left drawing hand.

Andy Thomas Interview

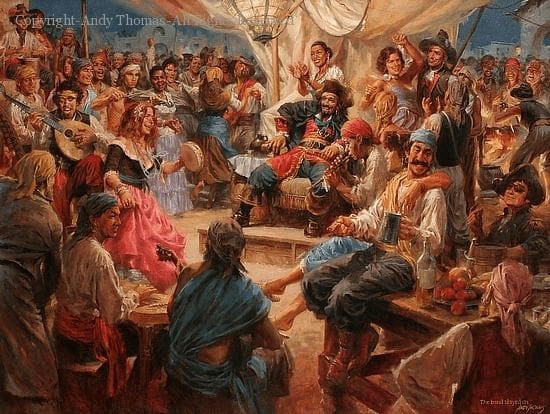

I first met Andy Thomas more than 20 years ago while participating in the Midwest Gathering of the Artists Show in Carthage, MO. His talent was obvious, so to see his career explode as it has in recent years as a painter of western themes, well, it’s really not that surprising.

His paintings now garner well into the five figures.

Thomas captured, in his trademark style, many of the participants in the Midwest Gathering of the Artists Show with whom we became friends. I’m depicted with the highwheeler, indicating my love of cycling.

Mark Smith, co-founder of the Greenhouse Gallery of Fine Art in San Antonio, TX, and exclusive representative of Thomas’ work said, “Andy represents one of the most talented and creative painters working today. He has gained wide respect for his portrayal of the horse and its historic role in the old west and, as a result, has become one of the most sought out and collected painters of the historic time period known as the Old West. Collectors respectfully refer to Andy as a great “story teller” and compare his paintings favorably to the works of Remington and Russell. Through his paintings, Andy allows the viewer to be a participant in the scene rather than a spectator”.

At the Coeur d’ Alene art auction in 2009, this painting set an auction record for Thomas’s work, selling for $110,000

Things could have turned out quite differently. I remember being notified in 1996 that Andy had been injured in an explosion while working in his shop. His hands had been severely damaged. I couldn’t believe it, and feared the worst. Later, in an attempt to return to painting prematurely, he further injured his right hand. That’s when he took up painting with his left hand, producing some amazing work. Now that both hands are fully healed, he is able to paint equally well with both hands simultaneously while working on two different paintings…doubling his production…just kidding.

Andy didn’t begin his professional career in the fine arts. After graduating from high school, he went to work for Leggett & Platt, Inc. in their Marketing Service Department, an in-house ad agency. During this time he also attended Missouri Southern State College, graduating magna cum laude with a degree in Marketing Management in 1981. Employed for 16 years with the Fortune 500 company, he advanced to become its staff Vice-President before finally resigning his position in 1991 in order to pursue painting full-time.

I’ve always accused Andy of having a photographic memory because of his uncanny ability to record things he has seen or experienced. He denies my claim, but there is something extraordinary in his ability to capture a moment in time…to tell a story that is capable of transporting folks to another place and time. If he had lived in the old west, cowboys would have paid him to join them by the campfire and spin a yarn. His vivid memory and imagination enable him to create paintings pregnant with action and drama…paintings sought after by a growing number of collectors.

Desiring to learn more, Andy graciously agreed to an interview which I am pleased to share with you. I think you will find it interesting.

What would be your definition of art? I gave this a great deal of thought my first year as a full time artist. As I looked around and identified what I thought was art (including architecture, movies, comedians, choreography, etc), they all had two elements. The first was communication. That is, they all had to be received by the viewer or listener. The second was they were original in that there was no formula used. Sometimes I would find myself thinking “Gee, that’s great and I don’t know why”. So, I define art as creative communication. The real question for an artist is, “Who am I wanting to communicate with?”

You define yourself as a painter of history, how do you go about translating the written account into a fully realized painting? Painting an actual event is a challenge. If I am true to factual history, many of my creative tools are taken from me. Still, I can be somewhat creative and use my craft and research to produce a work that people appreciate. Historically based paintings that are not a specific event are much easier. I get much of my inspiration from reading personal journals and memoirs of the time because they are full of feeling and impressions.

Your western themes have really caught on with collectors, why do you suppose that is? There’s a little boy inside me who wants to be a cowboy someday. I suppose that makes me paint westerns with enthusiasm.

How did you find your individuality as an artist? By painting many styles and subjects until my own style emerged.

Do you consider the process of painting more important than the result? No. The final painting is always my ultimate goal. However, I’m always amazed how indifferent I am about a painting that is finished. It is the past and I am looking forward to the next painting. Luckily, my buyers don’t feel the same.

What part does photography play in your work? I use many photos for background reference but really only paint directly from photos for rifles or pistols and sometimes for hands. In the course of painting a figure, I often pose myself and take a photo to check anatomy or clothing wrinkles.

Does plein air painting play a part in your work? Plein air was one of the many types of painting I did to develop as an artist. I never learned to enjoy it and I only do them now for the fellowship of other artists.

What is the major thing you look for when selecting a subject? I have learned to fumble around with ideas until one gets me excited. Lots of thumbnails and color studies.

What is your major consideration when composing a painting? That’s tough to answer. I will say this; If my little thumbnail looks like a good composition, the color study will have a good composition as will the finished painting.

How thorough is your initial drawing? Very, very loose. I really let details emerge and develop as I paint. Sometimes I move arms or legs many times in the process.

Describe your typical block-in technique. My usual procedure starts by taking a photograph of my color study and printing the image on an 8.5″x 11″ paper. I then draw a 16 square grid on the photograph. I prepare my large canvas by staining it with a brown/black mixture (ultramarine blue and transparent red earth). I use the same mixture to brush in a 16 square grid on the canvas and redraw the color study.

At this point, I usually block-in the whole canvas with thin color and soft edges. The washed in canvas should have the correct color, value and composition of the finished painting with no details. I then begin the slow process of finished, detailed painting by working on individual figures or small areas and working around the canvas.

How do you decide the dominating mood for a painting, and how do you maintain it? My paintings are narrative, storytelling affairs and the mood of the painting is part of the story. The mood is controlled by the choice of light source, the deepness of the shadow areas and the body language and expressions of the figures. Since I use figures often, body language is important. I never paint a man just standing. My men stand in defiance, or in fear, or with boredom, etc. That’s what I try to do, anyway.

What colors are most often found on your palette? Ultramarine blue, transparent red earth, Venetian red, cadmium yellow deep and zinc/titanium white are always on my palette. I keep cadmium yellow light and cadmium red available but rarely use them. My vision is color weak so this limited palette suits me.

What are the key points one needs to know when creating a true sense of atmosphere? Light source, light source, light source.

You have a strong affinity for illustrators of the past, why is that? I think they were the best artists. They did paintings that fascinate me. They have not had a chorus of art historians promoting them.

So, if you could spend the day with any three artists, past or present, who would they be? Howard Pyle, Charles Russell and Frederic Remington.

What advice would you have for a young artist/painter? Here’s the best advice that was ever given to me. I asked an artist I greatly admired the same question, hoping he would tell me something like “paint horses, you can make good money painting horses” or “go to this show and you’ll sell out”. Instead, his answer addressed my artwork; “Whatever you see as your weakness, attack it. For example, if you can’t paint hands, practice until you can”. I followed his advice. The same artist, when I asked him what was the most important thing about a painting, immediately said, “The reason you wanted to paint it in the first place”. Perfect answer. The artist was John Pototschnik.

What advice do you have for a first-time collector? My experience shows me that people who only buy artwork they personally like are forever happy with their choice. I was always uncomfortable when people looked at my work for decorative or investment reasons. I do know that a painting that you enjoy doesn’t require maintenance or your time like so many other things we buy.

When you become discouraged and feel the well is dry, so to speak, what do you do? I look at other artwork. For instance, I spent a great afternoon the other day making a list of my favorite all-time paintings and printing slick copies of them off the internet. I never really finished the list and before I was done I had ordered two more art books. But I had fun and was ready to paint.

Finally, Andy, if you were stranded on an island, which three books would you want with you? Atlas Shrugged (because of the message and because it would take being marooned to get me the time to reread it), and True Grit (better with each rereading). My third book would be some sort of survival guide so I wouldn’t be hungry while reading the other two.

Thanks Andy for a wonderful interview.

www.pototschnik.com

Dianne Massey Dunbar Interview

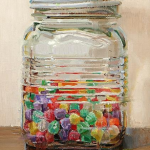

“I paint ordinary objects and scenes from everyday life. While I have the highest respect for artists who paint vistas and exquisite nudes and the like, I believe that there is a great deal of beauty in the world that often goes unnoticed. The amazing color in raindrops, the variety in fallen autumn leaves, the interesting greens one finds in a stack of French fries, there are endless opportunity for paintings. My hope is that people view the world just a little bit differently after seeing my paintings.”

What is so amazing to me is her fabulous ability to take the most mundane of objects and transform them into delectable treats. How can someone take a simple tube of lipstick, or plain glass bottles, or even raindrops on a windshield, and transform those things into objects of desire…paintings sought after and cherished? Dunbar does it and makes it look easy. How she does it is what this interview is about.

Mark Smith, co-owner of the Greenhouse Gallery of Fine Art in San Antonio, said, “To view one of Dianne’s paintings is to experience complexity in its most artistic form. Most often, her choice of subject matter is quite complex, challenging and can be categorized as “crazy”. However, this type of complexity is the stage that most accurately reveals Dianne’s stunning sense of color and expert brushwork. Dianne is a master of articulating her inspiration and the “story” that she finds in the most mundane and overlooked objects and moments.”

And now more from Dianne Massey Dunbar…

“I want to thank John Pototschnik, whose work I have been watching for some time now and greatly admire, for asking me to answer a few questions. I have tried to answer these questions honestly and openly and I truly hope that my comments are helpful.”

For me, the intellectual part of painting is the process of designing the painting, the drawing involved, and the problem solving along the way. It is not sentimental and it frequently is not much fun. There is skill and experience that an artist draws on, and every painting, no matter how well it has been thought out, has an area somewhere that is troublesome. There are times when work is tedious or even boring. The emotional part of painting is for me what I like and don’t like, the subject matter that I paint, the thinness or thickness of paint, the “play” time I have with a painting, and the colors I may choose. And for good or for bad, I emotionally invest in my paintings.

Finding subject matter that is exciting is personal. I am drawn to simple common images: candy bars, cupcakes, rain on my windshield, jars, dishes, road crews, and reflections. After that, almost all of my preparation for each painting is intellectual and frankly a little tiresome. I study various compositions and value arrangements for my chosen subject matter long before I put brush to canvas. I tape the value studies upside down in my kitchen and study them to see if the design and the shapes are working. Once I have a design, only then do I begin painting. And for me, the beginning and early stages of a painting tend to be thoughtful and deliberate and even a little intimidating.

However, I absolutely love to play with paint, so when I have a painting far enough along, I can then begin to have fun with it. I might decide to smear paint, or flick it. I use any number of implements to play with paint, from the jagged edge of gum wrappers to torn pieces of paper towel rolls to palette knives to inexpensive brushes that I have cut gaps in. Today I experimented with my rubber kitchen spatula (I had fun but unfortunately was not happy with the result!).

I think non-artists have a notion that art is the result of “inspiration”. Well, there are times of inspiration, when instinct takes over and something happens on a canvas that I probably can never do again but I look at it in wonder. However, those times are few and far between for me. Being an artist is very much like other careers, there is leaning and thinking and hard work involved.

Describe your typical block-in technique, the thoroughness of your initial drawing, and the part photography plays in your work? I have more than one process that I use, depending on my subject matter. If I am doing a relatively simple still life, between one and three objects, I will do one or two quick thumbnails on a piece of inexpensive canvas board, and if I am happy with the shapes, I will begin to sketch those shapes in on my canvas. On the canvas, I may do a very simple sketch, or a more complete sketch, either very lightly with pencil or with a small brush. I then paint, working from background to foreground, massing in the large areas of a single value without much regard to detail. Once I have the large value shapes in, I can begin to break them down into smaller shapes, etc. I try to work on gradation and edges as I go along.

On the more complex paintings, I generally use photographs and work with a grid system. I might start with 20 or more digital images that I study. I look at the overall design, and see what happens when I zoom in or crop the images. I narrow these down to maybe the top five and I have those printed at my local camera shop. Then I make black and white Xerox copies of the color photographs. After the copies are made, I use inexpensive poster paint in white, gray and black and paint directly on the copies exactly where I think I want the light value, the medium value and the dark value. For each photograph I might do two different value studies, to see what the resultant design is. I do this by hand instead of computer because I can make all kinds of decisions when I work by hand that might go unnoticed otherwise.

Every part of that image needs to fall into one of those three values (I have been known to work with four values, but that gets very complicated). I then tape them up in my condo and live with them for a day or two, turning them upside down and sideways to see if the design is satisfactory. It is tedious, but I have found this process works for me and I have more successful paintings. After I have a design I like, then I have that photograph enlarged. However, I keep the value study because that is my “roadmap” for the painting. So, I paint the image that I have chosen, using the values of my value study. If I am working on a square canvas, I might work from an 8″x 8″ photograph, and work on a 16″x 16″ canvas, or 20″x 20″ canvas or even a 24″ square canvas. The photograph is taped to lightweight cardboard and I use a sewing needle and thread to grid the photograph so that if necessary I can move the thread aside to see what’s underneath. I usually use 1″ squares on the photograph. I grid the canvas (the canvas must be the same proportion as the photo you are working from) with very light pencil lines, usually in two or three inch squares. I then paint each square, starting from the upper left hand corner and working to the right. After my canvas is painted, then I go back and make necessary corrections, work on edges, simplifying, etc.

I use other colors in different situations, especially Zinc or Transparent or Flake White Replacement. There are times I really need Indian Yellow. Caucasian Flesh is a very useful color in a number of situations. I also use Venetian Red or Naphol Red and a number of other greens, especially Emerald Green Nova. I mix my blacks, but I do have a tube of black that I use if needed.

Some of these are quite transparent in nature, and some opaque. An artist needs to know the tinting power of different colors and use the intense colors sparingly (Alizarin Crimson and the Phthalos immediately come to mind). However, a lot of wonderful effects can be achieved with a more limited palette, so you do not need all these colors to produce wonderful paintings. Indeed, if you are new to painting, you would probably be best served by using a more limited palette.

How do you decide on a dominating color key for a painting, and how do you maintain it? I use the subject matter to guide this decision. If it is an overcast cloudy day, then much of my painting will be grayish. If I am painting toys, obviously the colors wil be much brighter. However, too much pure color is overwhelming. I mix almost all of my color. I reserve pure or intense color only for small splashes or small areas.

You have entered a number of significant art competitions. Why are art competitions important to you and how do you go about selecting the paintings for these shows? I usually enter two to three art competitions per year. I started by entering local and state competitions, and when I was comfortable with those, I started entering regional and national competitions. There are two main reasons that I enter art competitions. The first one is to see how I stack up against other artists. Secondly, I enter competitions to hopefully have my work seen by other artists, collectors, galleries, and even magazines. There are other good reasons as well: meeting other artists, being inspired, and being challenged. Some art competitions have seminars that an artist can attend to learn and expand their knowledge on any number of topics. And, let’s face it, competitions can be fun! As far as selecting a painting, when I have what I feel is a good to exceptional painting and a deadline for a show that I want to enter is approaching, I will try to put the painting aside and keep it to enter in the show. Be aware that competitions can be expensive, there are entry fees, shipping and storage fees, and perhaps travel fees if you decide to attend the opening.

What do you think of that amazing interview, folks? Personally, I so appreciate Diane’s willingness to submit to this interview…and being so thorough in her answers. I hope you do also.

Click here to receive John Pototschnik’s monthly newsletter

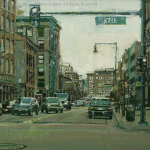

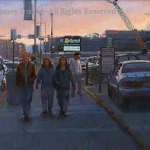

Marc Hanson Interview

“Painting from life, plein air if outside, is critical and necessary to me for what I want out of myself and out of my Art”.

Besides the airplane, he’s also building a boat…a 12′ flat bottom rowing skiff…and it’s all done except for sanding and painting. Add to that his landscape painting and I think he’s pretty much got it all covered…land, sea, and air.

When you talk about Marc Hanson though, you’re really talking about a man who is absolutely dedicated to the craft of painting. He is most at home outdoors in the open air, brush in hand, capturing on canvas his excitement about the natural world. He feels most confident expressing himself in this way, visually, through painting and drawing as opposed to writing and speaking. That’s probably not uncommon for us visual artists, but believe me, Hanson is no slouch when it comes to writing. As you will see in this interview, his answers are seriously considered and clearly stated.

Marc’s primarily a plein air painter and he’s out there rain or shine every season of the year. He works mostly in oil, but also in pastel…and sometimes even in qouache. Because of the hundreds of paintings he’s done on-site, there is an absolute authentic reality associated with his work whether the paintings were conceived in the studio or outside.

I had the pleasure of meeting him at a plein air event we both participated in last year in Kansas. Organized by Kim Casebeer, a group of us spent several days painting in the Flint Hills and Steve Doherty, editor of Plein Air magazine, reported on the event in the Feb/Mar 2012 issue.

It was a challenge selecting images for this blog. It’s like being forced to choose just one M&M candy from a large bag of many colorful, delectable possibilities. They all taste the same, but oh, so many choices…which one to choose? I wanted to take them all, but…

That’s a big question, one that much deeper thinkers than me have pondered and explored. But…my take is that Art is the expression humans use that incorporates a skill other than communicative speech, to show others what they feel about the world around them. Music, Dance, Visual Art, Poetry, Prose…these are all ways that we humans use to talk about the world around us, in an intelligent way, based on our emotional reaction to our world, that is unique to our species. Other creatures build amazing structures, have incredibly beautiful song and sound, and they communicate with their own kind. But we are the only species that can ‘create’ beauty, ART, as an expression of our emotional existence.

How do you define your role as an artist?

My role as an artist is to be honest with myself, so that I make Art that is solely mine. I have no illusions that what I do does or will matter to anyone other than me in the end. Not to slight those who collect it, and compliment me on it, that’s an honor that I never discount. When Art is your life, however, you live it, breath it, are up and down with it. If I stay true to myself and honestly evaluate what and how I’m creating it, then all of the other factors will fall into the place that they belong, whatever that may be.

How does one find their individuality as an artist?

Paint, paint, paint! That sounds simple, but it’s the key. Once one has the skills in hand to be able to self evaluate, with occasional help from your peers, diving deep into your own creative space and working hard is the best way to see who you are as an Artist. Style, or individuality, will come out of you, it can’t be held back, if you’re really working hard at your art.

Your paintings are uniquely yours because of the many paintings you have done. I suppose your personality is reflected in your work?

I’m all over my work. My background as having always been interested in bugs, birds, things that bite and slither, large furry things, and where they live, has made me pretty sensitive to Nature and her color and mood. I’m fine being with myself, with being in a quiet place and state, and my work reflects that I think. I’m pretty happy about life. I don’t paint dark and tragic, unless I’m painting a severe thunder cloud…and that’s fun to me.

Plein air painting is pretty important to you, just how important is it?

Painting from life, plein air if outside, is critical and necessary to me for what I want out of myself and out of my Art. Life is where the truth lies, the truth in color, in spacial relationships, in texture, in shape and all other visual aspects of the subject. Photographs are a hollow substitute, one that I am always hesitant to use, but do. Painting from life is a joy, painting from photographs is pure drudgery in my opinion.

What is the major thing you look for when selecting a subject?

I look for something that makes my ‘painting eye’ light up and begin seeing the possibility for a painting in it. I’m not looking for a thing, I’m looking for a combination of the elements that make a painting, first the light followed by how that is affecting the color, edges and design. What is the impact on me and what is it that caused me to be interested in painting the subject in the first place.

Do you consider the process of painting more important than the result?

No…Every part of painting, starting with what I feel is most critical…the Concept…is important to the Art. The Result is the product of all parts of the process, the Concept, and the implementation of ones techniques and skills. The quality of the Result is tied to the level of skill and maturity of the artist, meaning that they are both as important in the end.

You speak of the importance of having a concept in mind before painting. Do you let the subject determine that concept or do you create the concept and use the subject only as the starting point?

The subject is raw material for a concept. Concept is #1numero uno to me. A concept has to at least be thought of before any other element or design principle can have a purpose in a painting. If you don’t know what you are going to do, what your concept for the painting is, how do you use those elements? I’ve painted paintings to music, emptied my head, had no concept whatsoever other than to listen to the music and apply paint according to how I felt about it…almost concept free painting. I see many students, who until I harp on it, have no concept when they begin…and they usually flounder until they decide ‘why’ they’re painting the painting. That does not mean that a concept locks you into anything, it only means that you have a reason to proceed.

How do you decide on a dominating color key for a painting, and how do you maintain it?

I let the color harmony of the scene determine that for me. I will squint, turn my head nearly upside down or sideways to try to get a sense of what the color of the light is in the scene. Then I am very careful to pay close attention to my color mixtures so that they are in that harmony as I put them up. I test each color on the painting each time, several times, before I commit to it. Another reason for painting from life, the color harmony or ‘key’ is already there. The problem is how not to destroy that if it’s what you want in the painting.

What is your major consideration when composing a painting?

I look for a way to set the stage so that I can talk about what it is I have to say. It’s about that simple to say, though complicated to implement.

How thorough is your initial drawing?

That depends on the complexity of the situation. But I’m more of a ‘large shape’ kind of painter now. I get the big proportions going, simple shapes as possible, and then refine down to the details from there. So, a complex drawing would be counterproductive. That’s the way I paint today. I came out of the ‘tracing paper overlay’ world as a younger artist/illustrator…and am happy to let that go.

What colors are most often found on your palette?

Titanium white, Naples yellow (light version), Cadmium lemon yellow, Cadmium yellow deep, Yellow ochre (lighter version), Cadmium red light, an Earth red (Venetian, Terra Rosa, English red light, etc), Alizarin crimson, Transparent oxide red, Viridian, Cobalt blue, Ultramarine blue deep, and often now a blue like Manganese blue…and sometimes Chromatic black.

Describe your typical block-in technique.

One way is that I get a cheap 1-1/2″ or 2″ bristle varnishing brush (hardware store variety $1.79) and start knocking in big blocks of color pretty fast. Usually using a colored block-in that gives me an idea of what the large masses of color will look like in the composition. Then I lightly wipe out most of that and begin to restate the drawing or just begin applying areas of color.

Do you paint in layers?

In the studio, yes I do. And on multi-session plein air landscapes I also do.

What are the key points one needs to know when creating a true sense of atmosphere?

I might just answer that by saying that if you just pay attention to the relative color and value relationships, you’ll be fine. However, having just taught a class, I know that’s my experience talking. Studying recessive situations from life, understanding recessive color theory, then going out and trying to make your color recede and reflect the atmosphere that you’re painting is a way to improve that in your work. Every situation is different outside. Unless an artist wants to paint a generic reflection of the landscape, studying and painting from life is the only good way to create the atmosphere that you’re seeing.

How much of your work is intellectual vs. emotional…and how would you define the difference?

I would say that it takes the intellectual to produce the emotional. The process is intellectual, although as time goes on, some of painting is almost intuitive…things like mixing and applying paint (that comes up as I’ve just come off of teaching a workshop. It’s not automatic to students, still in the low end of the learning curve, how to physically make a painting…things like how to mix and apply paint is a big deal to them). The quality of the end result has to be full of the emotional or it will be but a rendering of a ‘thing’. When the masters reach that place where the two mesh…the intellectual and emotional are working in harmony…they produce poetry…Art.

What part does photography play in your work?

It plays a big part when I’m in the studio, along with field studies. Especially if I’m needing to paint Cape Cod when I’m in my Minnesota studio. One reason I just relocated to Colorado is to be able to be outside painting more often and not stuck in the studio so much. I always try to only paint an area that I have first painted from life, or at least where I’ve done some work from life to be able to know how the light in that area looks. If I need to pull out the photos on the computer, I use the photo as a starting point and let the painting emerge and grow into it’s own thing, away from the photo usually. At that point, I barely look at the computer.

What are the major problems encountered when translating a field study to a large studio painting?

I would say that if you expect to recreate the field study, you’re bucking up against a big wave. I realized that the field study is there as a starting point into a different voyage, to give you some notes that you can use to create a brand new image with it’s own inherent qualities that were not in the field study. Trying to replicate the 4″ swish of an emotional brushstroke at a scale that is 3 or 4 times larger in all dimensions…is nearly impossible. The field study is a ‘note’, maybe a pretty finished one able to stand on it’s own, but as far as a larger studio painting goes, it’s just a reminder for me.

I notice you work in both oil and pastel, why do you do that, and what are the significant differences?

I started pastels many years ago because I had a show coming up and needed more work, faster. I took to it immediately. They have the sensitivity for me that is attractive for rendering natures’ textures. I like the broken color that is achievable with pastel, and it’s taught me a bunch about color and using color in the oil paintings that I wouldn’t have thought to mix on my own. Otherwise I paint with pastels in the same basic way that I paint with oils…dark to light, thin to thick. I break the pastels into brushstroke sizes and use it as sweeping strokes. I don’t draw linear strokes with it. I think it’s always good to switch mediums from time to time. I also use gouache for field studies pretty often. That’s my third favorite medium.

What advice would you have for a young artist/painter?

I like what Henri said…to the effect…paraphrasing…’Discourage and dissuade any child who wants to become a painter and if they still want to, then they may have the fortitude to withstand it all, and succeed’. Wish I had the quote at hand on that one, but that’s basically the idea. I’d tell them that they need to seek out good advice and training, learn to draw first and foremost. I’d also tell them to try every medium, technique and style that they can. Learn about all of the materials and techniques that they can. Too many painters I run into today start with a workshop, learn about one kind of brush, one palette, one kind of canvas board. Materials are like musical instruments or dance shoes…every artist finds the ones that work best for them. If all they use is the ‘one’ that their first instructor told them to use, they may be missing out on the ones that take them to a higher level of creating art. Young artists are in a great place right now. There are academies, ateliers, workshops and schools all over the country from which to pick either a designed curriculum program, or in an a la carte way.

What advice would you have for a first-time collector?

I would have to say that is really dependent on the level of the spending the collector can do. If it’s a few hundred dollars, local galleries and art shows would be a way to begin to follow the artists and art that appeals to them. Also, educate themselves by looking at magazines like American Art Collector, American Art Review, Southwest Art, etc. I’m sure that gallery owners would be the best ones to answer this question, so I’ll leave it at that.

If you could spend the day with any three artists, past or present, which would they be?

Sorolla, Levitan and Monet.

Who has had the most influence on your career, and why?

My Dad. He was a part-time artist and always my biggest supporter and encourager to become an artist or anything for that matter. He shared all of his knowledge with me about art materials, from crowquill pens and India ink, to woodcuts, oil pastels and oil paints. He even did scrimshaw later on in his life. I would not be doing this today if it were not for the hours of his life he gave me.

How important are art competitions and how do you decide which piece to enter?

I like to enter some, OPA is my main competition. I use it as a yearly barometer for my progress. Nothing like seeing your work amidst the work of your peers, year in and year out, to see how you’re doing. It’s an awakener.

Thanks Marc for a great interview and your willingness to share your thoughts with our readers.

- Marc Hanson website

- Blog

- Addison Art Gallery

- American Legacy Gallery

- Elizabeth Pollie Fine Art

- Ponderosa Art Gallery

- R.S. Hanna Gallery

Click here to receive John Pototschnik’s monthly newsletter