Henry Ward Ranger was one of the leaders of Tonalist painting. Ranger said that “Tonality to us means just one thing and but one thing. If you were to give it an arbitrary definition you might say, harmonious modulations of colour.” Others might say that you see the landscape through coloured atmosphere or mist to get an evenness of tone. The Tonalists focused on (or perhaps preferred) an overall gray tone, blue evening and night scenes were particularly prevalent. The French Impressionists laid down colour against each other to gain a vibrancy without making any attempt to blend them. American Tonalists usually mixed colors after applying them on the canvas – working to gain a harmonious paint surface rich with a variety of edges. As noted by Dr. Lisa Peters of Spanierman Gallery: “Although the Tonalist movement was established essentially as a reaction against impressionism – in the perception that it was overly scientific and a foreign import – many American artists felt free to combine aspects of the two styles.”

So, the Tonalist artists were concerned primarily with creating a “poetic vision” – suggesting in pure landscape the feelings of reverie and nostalgia. They generally did plein air sketches or studies and then painted larger studio versions – often these larger painting might be “from memory” (the studies having been discarded).

Birge Harrison and Arthur Hoeber both were tonalist related. Harrison wrote a book “Landscape Painting” (published in 1909) taught at the Art Students League in New York City and the League’s summer program at Woodstock where he perpetuated his own “moonlight and mist” atheistic. A good example of Harrison’s work is his nocturnal painting of Fifth Avenue in New York. His student and friend, John Fabian Carlson continued his focus at Woodstock and his book on landscape painting has been widely used by student artists. The concept of being reserved in the use of color is not only a concept of tonalism. Sir Winston Churchill, in his book, Painting as a Pastime, is very clear on the benefits of maintaining a strong reserve of color.

Education

Critiques Along The Way

From our days of shouting “Look Ma, no hands” when we first balanced a two wheeled bike, we’ve looked to others to recognize and hopefully applaud our accomplishments. As artists we would be advised to seek constructive criticism from others who are sensitive to the process of creating art and are aware that our art is a personal expression of who we are.

From our days of shouting “Look Ma, no hands” when we first balanced a two wheeled bike, we’ve looked to others to recognize and hopefully applaud our accomplishments. As artists we would be advised to seek constructive criticism from others who are sensitive to the process of creating art and are aware that our art is a personal expression of who we are.

I believe as oil painters we travel the path to master our craft with a common goal of accurately expressing our view of the world with our own recognizable style. Some of us have been on the path longer than others and have reached this specific goal. It is not a race and every artist travels at his own pace.

When one declares themselves an artist they become one with other artists who understand and appreciate the process of laying bare your emotions on canvas. It would be unfair to compare a beginning artist with an established artist; realistically, to compare artists is like comparing the “incomparable” apples and oranges.

I offer two critique stories about my art work and the lessons I learned. As a young artist I was thrilled to even call myself an artist. I moved to the desert southwest, immediately connected with a gallery and an article was written about me in the newspaper. New in town I hoped to meet other artists and soon an offer came to sketch and paint at the home of a local art patron, Winifred. Winifred, known as Win, loved the arts and artists. She built a state of the art studio behind her home, hired models and invited local artists to her facility.

After several weeks I felt comfortable with the group and was approached by Win’s daughter, also an artist, who suggested I might bring some of my paintings for Win to view. I agreed and thought it might help me progress to the next level. So I arrived at the next session with six of my freshly painted desert scenes for Win to critique.

I lined them along a wall and Win began to pace back and forth in front of them. It seemed like ten minutes went by and the suspense was unbearable. Then, what did my naïve, wondering, artist’s ears have to endure? Scathing, emotional, colored words spewing from Win’s mouth. I couldn’t believe her vicious tone as I gathered up my paintings and fled, resembling a beaten dog dragging his tail between his legs as she yelled after me, “How you think you are able to paint at all is the ultimate question!”

After the attack I came back the next week to sketch because I was afraid I would never create art again. It was my last visit. I realized her attack was unprofessional. A critique would have suggestions about composition, perspective, edges, color harmonies or some useful hint to improve. And if someone had forewarned me, I could have tried to thicken my skin to tell the old “Win Bag” she was in no position to critique art. Her critique was emotional, lacking constructive criticism and thus was not a critique at all. So there!

My second critique story is short and sweet. At a workshop at Kevin Macpherson’s studio in Taos, his class was outside painting around his pond. I could overhear his suggestions to the other students and every comment he offered was very positive. When he got to me he told me an area in the upper left of my 8 x 10 painting had some nice qualities to it. I actually thought it was messy looking but realized it conveyed more emotion than the other more precisely painted areas. Near the end of the workshop I told him about my observation and asked if he ever pointed out something wrong in a student’s painting. He said, “I encourage the artists with the things they are doing right and hope they will figure out on their own what isn’t working for them.”

What a contrast between these two critiques: one tore me down and the other built me up. I learned that a critique is really just an opinion. However, when expressed by a professional artist who has painted acres and acres of canvas and speaks from that experience with positive suggestions, it is invaluable. Learning to paint is a process and patience is to have its reward when all the disparate elements of creating art come together for you to create the art you dream about.

As a footnote, writers are artists too and the majority of the OPA Guest bloggers are practicing artists sharing their knowledge and insights, much like Kevin Macpherson did with me. OPA’s talented web designer has created this blog for us to enjoy with a simple way to send a comment to the bloggers to let them know if they connected with you.

Feedback inspires us and everyone benefits from reading other artist’s comments.

Make Preliminary Drawings The First Step In Your Portrait Process and Get the Painting Right the First Time

Every portrait painting is the result of a series of steps. Some artists have fewer steps than others, and most artists are eager to grab their paints and dive right into the color process. But those who simply pose their model and start painting are taking a lot of chances, such as improperly placing the model on the canvas or discovering a more interesting pose once you’ve already begun. After many hours of your hard work and your model’s patient posing, you don’t want to wipe it all off and start over again.

Every portrait painting is the result of a series of steps. Some artists have fewer steps than others, and most artists are eager to grab their paints and dive right into the color process. But those who simply pose their model and start painting are taking a lot of chances, such as improperly placing the model on the canvas or discovering a more interesting pose once you’ve already begun. After many hours of your hard work and your model’s patient posing, you don’t want to wipe it all off and start over again.

That’s why preliminary drawings are such an effective portrait tool because they help solve problems before they happen. Drawings let you map out your subject and get acquainted with all the hidden things you’ll need to know about him or her. Take bone structure, for instance — every skull is similar, but there are always subtle variations that can make a big difference in the portrait. You must be as aware of the unseen side of your subject as you are of the visible side. If you’re guessing, the viewer will know it.

Use drawings to get to know your subject before you begin the actual portrait. For some artists this may take no more than a few sketches and suggested values.

This kind of familiarity also pays off because with a live model, no matter how good a model he or she is, your subject is frequently changing. There are many muscles in the human head, more than in any other part of the body, and nearly all of them move when the expression changes on the subject’s face. If you can learn some thing about what muscles made the expression you want, then you can compensate for subtle changes (A smile, for instance, consists of much more than just upturned corners of the mouth.)

This kind of familiarity also pays off because with a live model, no matter how good a model he or she is, your subject is frequently changing. There are many muscles in the human head, more than in any other part of the body, and nearly all of them move when the expression changes on the subject’s face. If you can learn some thing about what muscles made the expression you want, then you can compensate for subtle changes (A smile, for instance, consists of much more than just upturned corners of the mouth.)

Put a little preparation into each portrait you do by starting off with preliminary drawings. You’ll soon find that a little investment up front can save you a lot of trouble later on, and it brings an important step closer to making your portraits the best they can be.

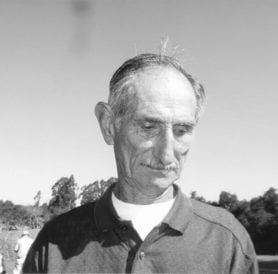

I have a good friend, Frank, who has wonderful bone structure. Every bone is right up front where I can see it. I snapped two photos of him, not pretty, smiley photos, but character studies. I wanted to show his bones and wrinkles off to their greatest advantage.

Portrait Pointer: when you can’t find a model who is willing to sit for several hours, go for photography. Be ready with your camera when a great face comes your way. Just remember, don’t just copy the photo, study the bone structure and value patterns the same as you would when using a live model. Measuring is very necessary. Remember, every skull is different. Don’t generalize. Drawing is not only necessary to portraiture but a beautiful and fun form of art.

Portrait Pointer: when you can’t find a model who is willing to sit for several hours, go for photography. Be ready with your camera when a great face comes your way. Just remember, don’t just copy the photo, study the bone structure and value patterns the same as you would when using a live model. Measuring is very necessary. Remember, every skull is different. Don’t generalize. Drawing is not only necessary to portraiture but a beautiful and fun form of art.

Practicing Art

It all began last fall as I was planning a trip with some artist friends to Italy to paint where Edgar Payne captured those marvelous orange-sailed boats in the early 20th century. I was really nervous. I live in the desert. I don’t know a halyard from a square knot and I knew I’d better start “practicing” painting boats. Two months before the trip, at the OPA conference in Idaho, I went to a demo by Ned Mueller and he advised us to get up every morning and, even before that first cup of coffee, head into the studio and paint a small study for exactly 15 minutes. No more, no less. So, I did just that, except I had my coffee in hand, for 64 days before my trip to Italy. Most of the 64 little paintings were done in black and white to help me with the values, but it also helped me to became familiar with the perspective and beautiful curves of the boat and the sails. It helped me so much that I still do it. Ok, sometimes I miss a morning, but it’s become such a habit that I actually feel guilty when I don’t do it. What do I paint now that I’m back on solid sand? Anything I want to paint. It’s just practice, after all. Although I can tell you that those little, 15 minute studies have grown up to become some of my best paintings. Besides being a great way to warm up my painting muscles (both physical and mental) this is a practice that really pays off.

1. I made an effort to find an art “support group.”

I remembered reading Art and Fear, Observations on the Perils (and Rewards) of Artmaking, by David Bayles and Ted Orland which describes a study about those artists with/without support groups. They studied art students for 20 years and discovered that the ones who had connected with other artists were more likely to still be making art. This connection was more important than talent in the long run.

I think that a good support group, with artists who you trust, is like a marriage that works: when you’re “up” you help them, when you’re down, they help you. Not often in the same place at the same time, but it works. Now I meet with artists at coffee or in one of our studios at least once and usually twice a week. We share show information, frame suppliers, etc., congratulate each other or commiserate and talk about anything that we’re thinking about art-wise over coffee for about 2 hours. We artists, like writers, lead very solitary lives, so this is an incredible way to leave the studio and still feel like we’re “working” and, of course, learning.

2. I rediscovered the joys of getting back to basics

I took a workshop with Skip Whitcomb and he had us working with an extremely limited value palette–white, black and one grey very close to either the white or the grey. Wow. Talk about challenging you to simplify!

Then I did some new color charts with a four color palette I was interested in trying. These exercises really helped me to find new ways of saying what I wanted to say with the paint and reminded me to just enjoy the process of painting, without always having a specific painting or show deadline in mind.

3. I remembered the importance of making mistakes–it’s how we learn.

“You make good work by (among other things) making lots of work that isn’t very good and gradually weeding out the parts that aren’t good, the parts that aren’t yours.” Art & Fear, p26

4. I set some new goals for myself–at least two paintings a week, good or bad!

I revisited old “friends”: some books are more dog eared than others–you know which are your favorites. I also made myself reach for the books that I’d never really spent any time with–I wanted to try new ideas on for size, taking the lessons of other artists and trying them for myself

6. I started to thumb through my old workshop notes.

I wondered, “Why do I keep writing down the same things?” I paid to attention to that and decided to work on those areas. In some cases when I revisited the lessons, lightbulbs went off! I was in a better place to understand some of the ideas now and actually put them to use in my work.

The short version of this is: keep practicing and find artist friends, even if they’re only in blogs! And, as my friend (and fellow artist) Joan Larue always says, “keep your brushes wet!” I’m reminded of the old joke, “How do you get to Carnegie Hall? Practice, practice, practice!” Just substitute “How do you get to the Metropolitan Museum of Art” and you’ll get my point.

Thanks so much for listening and please let me know how it goes for you!

How deep is your space?

At one of my always stimulating dinners with my late friend Zyg Jankowski, he said to me that the first decision a painter has to make about his work is a spacial one: how “deep” do you want to make the picture? John Carlson felt that every foot into nature counted; Ed Whiney had no interest in such realistic depth and recommended a student plan the composition on-site but walk around a corner to paint it. Over the years, I’ve been schizophrenic about the question. Under Emile Gruppe’s tutelage, I naturally followed Carlson’s path. Later, I experimented with a flatter approach , one which, carried to an extreme, can make the subject disappear in a series of flat planes.

Note: for a further discussion of these points, check out YouTube: