Early in the fall when life was humming along normally, I had some well-educated and well-connected women tour my studio. One of the women raised her hand to ask a question. She said, “I don’t know much about art, but I would like to know what comes first, inspiration or intention?” I am not one to think quickly on her feet, so I fumbled and mumbled some sort of response. I have been tossing this question around in my head for the last nine months. The reason I find it so important is that each one of us has our own unique way of creating our paintings. Taking a few steps back and analyzing our process might help us in the future when we seem to get stuck or have a block.

This period of time in isolation is nothing new for us. As painters, we beg the universe for uninterrupted time at the easel. Some of us may be getting just that, but finding it difficult to even begin to mix colors because of the graveness of our world situation. Others of us may have spouses and children at home, and time at the easel is impossible. We certainly have more time to pause and think. We may wish we could feel that “ah-ha” moment when a great idea comes to us and we begin to run with it. Our paths to inspiration are as different as we are.

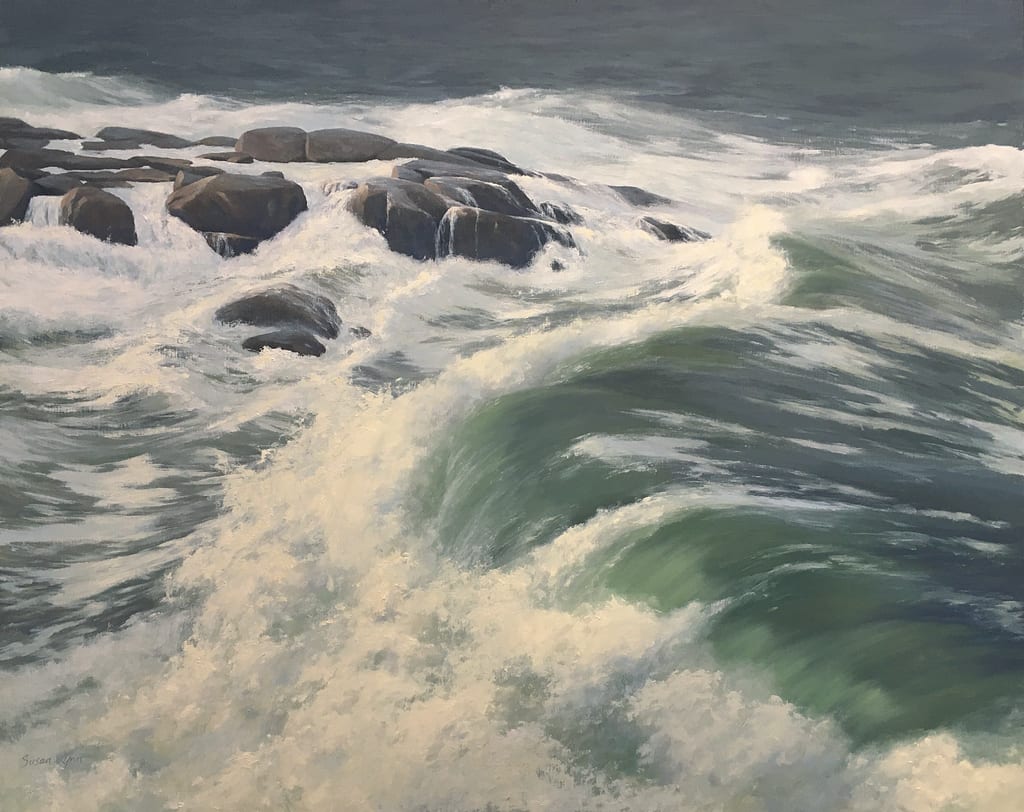

60″ x 48″ – Oil

For me, inspiration for new paintings is everywhere. It can be the petals of a flower, peeling open a grapefruit or the chubby cheeks of my granddaughter. One time as I walked through the grocery store, I held in my hand an unusual plum. I was fascinated and “inspired by” the amazing yellow-green color. Then I was “inspired to” use analogous colors and a variety of sizes to create a composition. “Oh Honey” was painted starting with this encounter in the grocery store. It may be an interesting exercise to trace the source of inspiration for our favorite pieces. Then I concluded that very often we are inspired, but not all of the time do we take action. It seems then that inspiration comes first. If we want to take this inspiration further and give it energy, then we direct our intention to this inspiration. Problem solved.

Not so fast. My friend Malachi Lawrence, who is an aerospace engineer, says intention comes first for him. An engineer may face a baffling problem that he or she intends to solve but all of their best analytical efforts may fail. But sometimes in the middle of the night, the inspiration for the solution comes! For some of us as painters, commissions motivate us. The intention to fulfill the clients needs comes first and then finding inspiration to create a painting comes second. Okay then, so it could go either way.

Then why ask this question after all? Because we all need to learn to tap into our own resources for inspiration. It made me want to dive deeper into how inspiration comes about. Is inspiration a voluntary or involuntary occurrence? I wrote an email to Scott Barry Kaufman, PhD, who is a humanist psychologist, author, researcher and speaker, known for his research on intelligence, creativity, and human potential. He sent me his article called “Why inspiration Matters” from the Harvard Business Review.

He writes, “Inspiration awakens us to new possibilities by allowing us to transcend our ordinary experiences and limitations.” Kaufman found that “Openness to Experience” often came before inspiration, suggesting that those who are more open to inspiration are more likely to experience it.We have all experienced a higher level of creative thinking for some of our paintings. However, we may find this inspiration is few and far between. We may have a total creative block due to many different circumstances in our lives. This pandemic could be causing major difficulty for some of us. Can we call inspiration in? Dr. Kaufman writes, “Mastery of work, absorption, creativity, perceived competence, self-esteem, and optimism were all consequences of inspiration, suggesting that inspiration facilitates these important psychological resources. Interestingly, work mastery also came before inspiration, suggesting that inspiration is not purely passive, but does favor the prepared mind.” The idea of being more absorbed in our tasks or mastery of work is something we can all strive for as we wait for inspiration. Two quotes from artists I saw recently suggest this.

“Inspiration is for amateurs: the rest of us just show up and get to work.” Chuck Close

“Inspiration exists but it has to find you working.” Pablo Picasso

During the most difficult time in my life, I believe I painted two of my best pieces. During the first half of 2018, my son, Stefan, was facing a very risky open-heart surgery and insurance was not willing to cover it. I spent countless hours researching this surgery to make the decision for him to have it or not, and months haggling with the hospital and the insurance company over benefits. My oldest daughter, Shelby, was struggling through a very difficult pregnancy and was due six weeks after Stefan’s scheduled surgery. During this time I painted “Orange Romance” and entered it into the OPA National. On June 18, Stefan pulled through this miraculous thirteen-hour surgery. As Stefan recovered, I was very consumed with worry for my daughter. With Stefan getting better every day, I painted “Tango in Yellow.” My granddaughter Camilla was born healthy on July 31. As I look back on this time and wonder how I was able to create these paintings, I can only say that it had been preceded by years of work on studying painting and understanding composition. Inspiration might come when you least expect it. One thing I do know is that I love to paint, and this love provided an escape from the harsh realities of life and I do believe they had some divine inspiration. Some higher power was at work and I really can’t explain, but I believe these works lifted me high above and carried me through these difficult times.

OPA National 2018, Dorothy Driehaus Mellin Fellowship for Midwestern Artists and Members’ Choice Honorable Mention

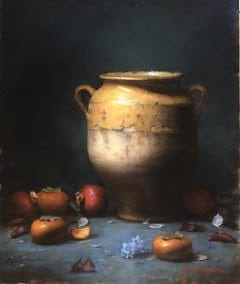

36″ x 24″, OPA Eastern Regional 2018,

Still Life Award of Excellence

These last few weeks have been unprecedented in our lives. I was living in so much fear and was unable to sleep. Confined to my home and reading too much news, I found myself comforted by the arrival of spring. First to come from the earth were the daffodils. The timing was perfect and very inspirational for me. I did five paintings of varied species that grew right outside my door because there were to be no trips to the florists. Exploring their unique forms and trying to create them in space became my obsession for two weeks. Interestingly they go from light to dark in overall feeling. Creating them gave me escape and eventually hope for what is to come. The botanist Dr. Robin Wall Kimmerer says, “The exchange of love between earth and people calls forth the creative gifts of both. The earth is not indifferent to us, but rather calling for our gifts in return for hers—the reciprocal nature of life and creativity.” I am surely more grateful for these Flowers blooming more than ever before.

Maybe the situation is different in your studio. A friend of mine, Austin-based artist Will Klemm, tells me, “Occasionally, if I’ve been away from work too long, or have had too long to ruminate on a ‘big idea’ for a series or a show, a kind of painter’s block can set in. If my first two strategies (cleaning up and pouring over) don’t work, I pull out a handful of unresolved or unfinished paintings. Then I work back into them, sometimes just a slight glaze will change everything, sometimes I completely obliterate the original with a palette knife. The point is to get the studio muscles moving again, without striving for any particular outcome.”

I have found that another way to do this would be to delve back into old photos on your computer. Try new cropping or editing and old photos can become new masterpieces. Inspirational ideas can come to us when we are not in the studio. Have you ever had your most brilliant ideas come to you while taking a shower or doing dishes? A quote from Mozart: “When I am traveling in a carriage, or walking after a good meal, or during the night when I cannot sleep: it is on such occasions that ideas flow best and most abundantly.”

Elizabeth Gilbert, author of “Eat, Pray, Love,” writes in her book, “Big Magic,” “I don’t demand a translation of the unknown. I don’t need to understand what it all means, or where ideas are originally conceived, or why creativity plays out as unpredictably as it does. I don’t need to know why we are sometimes to converse freely with inspiration, when at other times we labor hard in solitude and come up with nothing.” She later concludes, “All I know for certain is that this is how I want to spend my life-collaborating to the best of my ability with forces of inspiration that I can neither see nor prove, nor command, nor understand.” When one wonders where inspiration has gone in current work, I like Gilbert’s thought here: “You can believe that you are neither a slave to inspiration nor its master, but something far more interesting-its partner-and that the two of you are working together toward something intriguing and worthwhile.”

Here is my conclusion on the question that was asked of me last fall. If we keep working diligently at the craft of good painting and mastering our skills of composition, color mixing, and creating form on a canvas – if we do our part in the hard work, once in a while the painting transcends to a higher level. And often you may look back and say, “I don’t even remember painting that.” Maybe it was divine inspiration.

References:

- “Big Magic-Creative Living Beyond Fear” by Elizabeth Gilbert, 2015

- “Why Inspiration Matters” by Scott Barry Kaufman November 8, 2011 Harvard Business Review