Preppy was a term tossed around a few decades ago. It referred to the behavior of someone who went to a preparatory school. Or, it could refer to a logo-laden dress code. The word and the style fell from favor, but I’ve always liked the sound and decided that it could be re-defined and re-cycled for better use. All of us have heard the honored motto, “Be Prepared”. As artists, we must always make an effort to be so. But my new definition means a bit more. I would like for you to consider not just, being prepared, but also living in a state of preparedness. Living preppy.

Here are a few ways an artist can live a preppy life.

Live in a constant state of awareness.

Collect information, file visual data. You never know when some wonderful visual experience might happen to you. Be ready. Be aware that ideas are all around you. Write them down if you don’t have time for a sketch. You may be unhappily surprised if you don’t get into this practice. You’ll have a wonderful idea, see a great motif and believe that you’ll surely remember. But there is so much data attacking all the time that you may not remember. Carrying a small sketchbook, or even a little notebook is such a great habit. I wrote a note last week, “long deep blue morning shadows from tree line silhouetting foreground interest”. That doesn’t sound like much, but it was just the jolt I needed to remember the idea and return to the location at the right time of day.

Stay prepared by keeping your skills sharp.

This seems obvious especially if you are just beginning your artist’s journey. You are at that part of the learning curve where you must practice every skill such as drawing particularly, but also value study, color mixing, and even perspective. But as we advance, we get to a comfort zone, trust in our skill set and stop working to advance. So, you’ll stay just where you are. Drawing improves because you seek to improve it. And even the most gifted artist will tell you that they wish they drew better. Make practice of your skills a part of your life. Those tedious color charts are invaluable. Drawing either on your own, or with a group is one of the best things you can do to advance your art. And draw just for the sake of drawing. You will gain such amazing memory, both mental and physical. Your hand will want to do just the right thing. But it takes some dedication and commitment to keep those skills moving up the ladder.

Your drawing practice doesn’t need to be limited to life drawing. There may be no life group near you. So start a group. Get some artists together and commit to draw on a regular schedule. You could draw each other. You could have a day when you all bring a favorite object. You could go out and have “celebrate tree day.” Just draw.

Prepare before you begin. Solve problems before they exist.

Get into the habit of exploring an idea, a composition before you begin a painting. This can assume many forms and one or several may work for you. These will probably be different for each artist. There are a couple of things I do that help me get closer to success.

When I’m painting, especially en plein air, I always begin with a drawing. It is nothing formal, not even meant to be a good drawing. That’s not my purpose. I’m moving the pencil around, working it out. I’m studying the few basic values, thinking visually. I write on the drawings, make any note that might help. I start the process in the middle of the page and draw out from there, leaving myself plenty of room to change the cropping of the image. At this point, I don’t know the format, whether it will be a square, rectangle, perhaps a long format. That hasn’t been determined. I need to spend a little time with the subject and let that dictate the ratio. This also slows me down and that is a good thing. I notice that I have more failures when I jump in too soon. And I have noticed this in so many artists. We love to get right into the wonderful paint and may find out at an unfortunate later time that the composition is just not quite there. That is no fun and it is so difficult to try to change it in the middle. Why not begin with success? Then you can truly enjoy the painting process with less worry because you’ve nailed the composition. And since you’ve been practicing your drawing, no worries about getting it in correctly. I do these sketches inside as well.

To the left is a typical set-up for me. I always keep these composition drawings close-by as I go through the painting process. A little bungee cord keeps it from falling into the palette. I learned that detail the hard way.

I also love doing tiny color sketches. I may be preparing to attack a new subject or I may be searching for a fresh idea on a subject I’ve done often. Either way, I find it so helpful to take time to do some of these tiny studies. I mark off scraps of canvas, or even paper to the scale that I’m thinking about. I keep these around the studio so I can grab one that will work for a 4:5 ratio or a 3:4 ratio. And then, I may ignore that altogether and just go for a new ratio that suits the subject. These sketches are done very quickly, no detail, no fuss, just the big ideas. They often look more like abstract paintings than the subject I’m about to tackle. But that’s the point. If an idea works in the abstract, it works in every way. And because they are so quickly done, I tend to explore ideas more thoroughly. I do these on a separate day than I’m planning to start the painting. That way, I don’t rush to decide on the composition. I live with it a while, study it. There is such joy and freedom in this type of preparation.

by Joe Anna Arnett

So whether it is pencil sketches, tiny color abstractions, value compositions with markers, being prepared will not only save you from some problematic compositions, but it will advance your journey at a much more rapid pace. That’s right. That’s what I said. Taking the time up front, being prepared will get you to the goal more quickly and with greater success.

The page of composition ideas shown on the right was done in oil on ordinary brown paper, brushed with shellac. I taped off the rectangles in a 4:5 ratio for a later 12” x 16” canvas. The sketches are only about 4” wide. Use a big brush and leave the details out. Several of these will result in paintings later on. This type of exercise, done on a cheap, non-permanent surface, is so liberating. You’ll find that ideas begin to flow.

Oil on mounted linen – 12” x 16”

One of the little sketches developed further.

Think about it when you wake in the morning. What can I do to live preppy today? Take a sketchbook on my walk? Make notes of interesting ideas? Take time to keep my skills at performance level? Make preparatory drawings and studies? Think it out. Prepare and then go for it with great gusto knowing that you are prepared for success.

Nice going, Preppy!

Oil Painting

On Craft and Art

Today we live in the midst of a revolution of art the likes of which the world has never seen. Through the overabundance of art instruction and marketing via social media and the internet, great masses of student artists have emerged. Masses of artists created by multitudes of texts, online tutorials and workshops generated to suit the personality of and pocketbook of every enthusiast across the globe.

What has emerged is a condition of academia whereby the burgeoning artist unwittingly believes that there is a magical system of method that will mold them into a master artist. Yet the bulk of students remain students and never advance beyond craft. Although these artists may have completed numerous workshops and tutorials, they struggle to create a meaningful expression because they lack the ability to see with their heart. They have listened closely and diligently followed each process step-by-step but they have not learned to feel and experience their surroundings in order to imbue their work worth a singular personal expression. Without this quality, their art remains craft and exudes only a dry deadness and the viewer is not compelled to become a part of the artist’s world.

Art is not just what you want to paint, it is also and more importantly, what you want to say. The artist must utilize the basic foundations of art as a platform for their emotional response to a landscape, a still life or a portrait. Academia is not a means to an end, but a tool with which the student may sow the seed of opportunity to blossom into greatness.

All too often I witness students copying this or that artist and jumping from technique to technique and workshop to workshop as if they are collecting trading cards. They purchase all the latest easels, brushes and boutique paints advertised by their favorite artists. But all the while they are overlooking the point of the lessons. They never internalize their training and fail to make the processes a part of their individuality; consequently never moving beyond craft.

Great works of art are enduring because the artist has been uncompromising in their approach to express themselves fully through the language of art. They have put their blood, sweat, and soul into their work to the point where the art itself is indistinguishable from who they are and what they want to say. This kind of art speaks to us on a deep, intimate level because it speaks to us from the heart.

I propose that from the beginning of their academic training, students be coached and encouraged to pour out their heart upon the canvas. That with every step of their foundation they learn to experience the beauty that surrounds them in a way that expresses their particular perspective and personality. In this way I believe the student may not arrive at a stand-still or dead-end upon the completion of their training, but that they arrive at the beginning of art. They arrive at a place where they may create an enduring work of art which emanates the glow of their passion for life and their passion for art.

Know Your Subject Well

When I first left the studio to pursue plein air several years ago I would look for a variety of subject. Real variety. In the course of events I might paint a winding road, a lone tree, a bicycle, two old men in a diner, a summer lake at sunset, a tractor in the barn, a cow, a fence row – anything that caught my fancy. I ended up with a lot of mediocre paintings that had nothing to do with each other. My world was already full of mediocre paintings and I certainly didn’t need to add to that pile. They lacked verisimilitude. Veracity. I didn’t know any of my subjects well enough to communicate my vision.

In my former life as a studio photographer I created reality from pretty much nothing every single day. I once had a client come to me saying he needed an image to illustrate a wholesome breakfast. To him this was an oversized muffin and a hot cup of joe. This was the 80s and that was pretty much a healthy diet in those days. So I gathered the props and baked up some blueberry muffins. A dozen muffins gave me one very nice example; not perfect but near so. Blueberries everywhere. I sliced it in half, placed it on a white saucer, then laid on a square of butter softened just enough to say piping hot. This was flanked by a fabric napkin (light blue), a diner type butter knife (generic, but proud), a cup of black coffee (very black with a small grouping of bubbles to say ’fresh, fresh, fresh!’) and a check from the waitress marked ‘Thanks, come again, Becky!”

I shot this on 8×10 transparency film, processed the image, and then delivered it to the client. He looked it over and said, ‘Boom! That’s it. Love it! And my favorite thing… the little pile of crumbs on the plate under the muffin. That screams verisimilitude”.

Yes, verisimilitude – the appearance of being true.

Well, the whole thing was dripping with verisimilitude. It had everything that read reality – the right props, the right angle of view, the right amount of selective focus, and the right lighting for a morning sunrise. It had story. He had it right to single out the crumbs because in the end it is the detail that made the illusion hold up. Without those crumbs, it would all have been sterile and certainly less convincing.

That experience has stayed with me and I think of it as I make paintings. To pull off a representational image one needs to have verisimilitude – a judicious and efficient use of details. If there is enough information to allow the viewer to relax and understand the point of view then the artist can play with how that image is presented, and do it with abandon.

Drawing is a big deal; Probably more important than anything else. Without a good foundational drawing representational imagery falls apart and doesn’t hold veracity. No one believes it. A poorly drawn building, or old tractor, etc. can quickly devolve into a cartoon version of itself.

Drawing is mark making that describes how objects fit in space. Line work – thick and thin – can tell the story on shadow and highlight. Edges, real or implied, depend on line. My preliminary drawing is generally loose but heavy on perspective issues. I can move things around easily to get the composition worked out. As the piece develops I come back and re-establish my lines and edges. You know, build the edges, knock ’em down, and rebuild. But that structure, that foundational structure, needs to be there throughout. If I have a painting that just doesn’t work it is almost always because the drawing has no interest or is just flat out wrong.

When I go out into the field I look for the unusual point of view. Everything has perspective whether figure, landscape, or still life and that needs to constantly be heeded in the building of the image. If that perspective is accurately built into the foundation one can hang paint all day long on the thing. Monumentality is all in point of view. Angles – find angles that pull the eye into the composition. And if possible, exaggerate those angles. Stretch the thing and make it dynamic. I look for ways to distort without a noticeable distortion.

I paint a lot of vintage cars these days. I can’t tell you a lick about engines; my brain doesn’t go that way, but I do dearly love the look of an old car, particularly those that have gone to seed. They are such wonderful still life subjects with almost universal appeal. It’s my ‘go-to’ thing to paint.

I recently had a solo show. I wanted a cohesive series of work that would tell a story as well as showcase my interests and vision. So it was cars. I had over 40 plein air paintings of cars. I edited this group down to a manageable number and then fleshed out the rest of the wall space with larger studio paintings done from photos, and field studies. What I came to realize in the course of things was that I was developing a comfort level with my subject that freed me to put more energy in the way I put marks on the page. And that is really my thing, anyway.

I’m a process guy. I came of age when DeKooning, Rauschenberg, and Jasper Johns were still making stuff. Those guys knew how to throw paint and create new ways of seeing art. Put it down, scrape it off, and do it again. Abstract Expressionism is a long way from the direct observation of plein air but the mark making should not be dismissed. If the drawing is sound then the mark making process can run through the clover and give us new ways to see the world in front of us.

The point of all of this is to know your subject. Know it inside and out in the same way you might know a piece of music. Own it with confidence. Your viewer will appreciate it. They won’t know why. They’ll start with a comfort level that keeps them engaged with the image. They’ll get it – and then they’ll want to dive in for the good stuff.

by Lon Brauer

by Lon Brauer

by Lon Brauer

More Stuff I Wish Someone Had Told Me

Since then a few more thoughts have bubbled up.

1. It’s Hard

Nothing new here. I start every workshop by saying ‘painting is hard’. I love the Tom Hanks ‘it’s hard’ scene from A League Of Their Own when he states, “It’s supposed to be hard. If it wasn’t hard everyone would do it”.

2. It’s All Work

I used to stress about time away from the easel. Travel, shipping, framing, corresponding, photographing work and getting it out there, going to galleries and museums, visiting artist friend’s studios.… these things used to make me feel like time was being wasted. Then I had the glorious revelation that it’s all work.

This mishmash is what makes us artists, so just do these things well and enjoy each one. Hopefully with this acceptance comes a winnowing process to realize what it takes to be the most effective artist we can be. I have read that Norman Rockwell painted virtually every day, even Christmas. How he amassed such a deep level of human interest and understanding is beyond me. Genius is the likely explanation. We mortals have to actually take the time to interact, be places, see things, and get to the easel as much as we can.

3. Craft vs. Emotion

As we learn, it is natural to be proud of our skills, and push to develop them more. Think of a pianist who can fly through scales. The thing is, that is not very interesting to anyone!

To stay with the music analogy, a heartfelt Moonlight Sonata or Rhapsody In Blue or Let It Be can bring us to tears. Not because of craft. Because of emotion.

For people to deeply relate to our work they need an emotional connection along with skill. Of course each of us has to find that balance. No one is interested in a Moonlight Sonata with stops and starts and off notes and such (unless it is a near relative playing). Here the analogy slips. Note the strong interest in Folk Art, where the artists have little or no training. In painting, sometimes emotion connects more than craft.

Craft is important. And with visual art I do think people are impressed with great skill. But the greatest work finds a way for viewers to connect on an emotional level. That could be joy, serenity, shared interest, sorrow, passion… whatever. This is ‘unity’ and it can be sensed in any art form in a nanosecond. To see this in action, watch Susan Boyle singing the song from Les Miserables on Britain’s Got Talent.

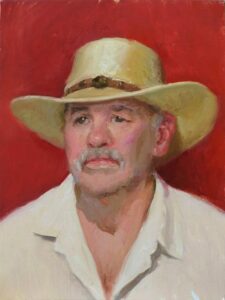

Ok, this is not new information either. I have been in groups like this on and off since the ‘80s. But if you had told me when we started nearly four years ago that our Wednesday Night Head Study Sessions would have so many benefits I would have been skeptical.

We paint a different sitter for three hours each week, and our skills have improved, our travel kits (a must!) are complete, we’ve grown so close, met so many interesting people of all ages and backgrounds, discussed so many things… I could go on. This, in a town of 1700 people, in a county of 20,000. You may have more than that in your neighborhood! So please, just do it! Paint from life with friends once a week, whether it’s portrait, still life, or landscape.

You can read more on our group and some practical tips on getting started here.

by Richard Nelson

by Richard Nelson

by Richard Nelson

5. Travel Kit

Mine is a traditional French easel (Creative Mark Safari 2, around $100) slightly modified so I can stand or occasionally sit, a palette, odorless mineral spirits, viva paper towels, an artist’s umbrella, and large tubes of the paint. This is always in my car, with a great LED light and stand, which works with rechargeable batteries or plugs in.

Happy painting, and may we all keep learning and growing each day we’re lucky enough to be artists!

PS- You can read the first installment of Stuff I Wish Someone Had Told Me here.

The Ideal Subject

“Sketch everything, and keep your curiosity fresh.” – John Singer Sargent

“The more I paint, the more I like everything.” – Jean-Michel Basquiat

As do you, I love to paint. I love nature, the experience of being outdoors. And I love many of the things I see around me, from morning to night: the sky, the light, clouds, people, water, plants, the city. And then I travel and see more new things. So I want to paint them all! I usually find my easel set up in front of a landscape, but not always. There are just so many things to see, to enjoy—life will not be long enough for me to paint all of my ideas!

But wait a second: before I get trigger-happy, perhaps I should consider the advice of those more seasoned than myself when it comes to selecting subject matter to paint. Let’s see: “Paint only in series, to explore a subject thoroughly.” “You don’t want any failures—only paint what you’re good at.” “Build your brand by painting one thing, so your collectors will know what to expect from you, and buy that.” “Practice so you can build a formula for making a quality product—that way you’ll know exactly what to do every time you come to the easel.”

There’s some wisdom in those words, for those who appreciate routine, want to avoid making mistakes, are satisfied with their current work and don’t have the need to try anything new. After all, the choice of subject matter is personal, and one could reason—just as in the case of a musician—that the choice of “the wrong song” could end tragically.

I’ve painted the landscape most of my life. It’s not that that subject is part of my “brand”, really. And the subject is so vast that I will never be able to paint it just the way I intend during each and every session.

I must say here that I’m not creating a product, though, but original art. If I’m going to spend my life painting, then I’d like my paintings to mean something. And in each of those paintings, I would like there to be more going on than just a rendition of an object, or several objects. How about mood, or emotion, the particular way light plays on a surface, or simply the creation of a striking design? Pierre Bonnard held that, in any painting, “The principal subject is the surface, which has its color and laws over and above those of object.” Edward Hopper left us word that all he “ wanted to do was paint sunlight on the side of a house.” In setting my own course in choosing exactly what to paint, I am beginning to believe that, as Theresa Bayer puts it, “The subject is a means to an end, the end being excellence in artistry.”

When I look at the work of other artists, I am always intrigued not only by what they paint but how they paint it. It appears that Richard Diebenkorn was curious in that way, too, when he said, “One wants to see the artifice of the thing as well as the subject.” Contemporary artist John Burton echoes the counsel of J.S. Sargent above when he advises the artist to “Draw everything, so you’ll be afraid of nothing.”

You might have seen some of John’s unusual concept pieces and world-building paintings that he has created, along with Bryan Mark Taylor’s ideas along those same lines. Both artists produce wonderfully large landscape paintings as well. But it is not so much their subjects that attract, or is the hallmark of their work: it is the years of perfecting their craft that comes through, be it a painting of a space vehicle, or a pinnacle in the wilderness. It’s that confidence from the daily solving of painting problems both technically and intelligently that we see in their works, no matter the subject. Jim McVicker is another versatile master- artist who comes to mind, and who also paints a variety of subjects: boats, portraits, figures, cityscapes, still lifes, et al. He isn’t afraid to try a new subject because well, he’s just not afraid to try it. As Jim has said, “There are a lot of things you could be afraid of in this life, but painting is not one of them.”

When you come to think of it, creating a painting is not a life-and-death matter, on the level of a surgeon operating on a heart, or a weapons specialist defusing a bomb (although I know that I have at times approached blank canvases in this manner). I want to be free within my own mind to try new things, to discover more of the world and why it appears the way that it does. And I also desire to improve my artistry, by expanding my repertoire.

This year I have intentionally done four things in my work as an artist that I have done very little of in the past. I went to New York so I could paint some cityscapes. I returned to watercolor painting as an “adjunct medium” and joined the National Watercolor Society for an upcoming show. I created three large-scale acrylic paintings, the largest I have ever done. And this month I took a still-life painting workshop with the still-life master, Jim McVicker. I am believing that these forays outside my Main Line will have cognitive, instinctive, and technical impacts across my body of work.

Bottom line: when we choose a subject to begin a painting, there are at least two levels of reality operating. One is the physical subject of the painting that we see (the Model). The other reality is the Design that we feel and create from that subject. In Art, of course, the Design is superior to the Model. No need to have anxiety about trying a new model, if you can design it the way you wish. At the very least, we could gain information or develop a renewed confidence that could be applied to our larger body of work.

So let’s go—it’s time to try something new!