A question that invariably is asked by students or observers during a workshop or demo is “How do I develop a style?” A comment I often hear from fellow artists at shows, galleries and museums is “I would recognize his/her style anywhere.” As artists, we want our work to stand out for its individuality, to be recognized as part of our body of work and for what we have to say as an artist even though our style may evolve throughout our career.

Brush mileage is the answer we hear for how to become proficient as a painter. I believe this applies to developing a style as well. Style develops while learning to master the elements that are essential in a great painting. When an artist takes on the prolonged study of painting, the essentials become a natural part of the artist. Hopefully, we will continue to learn and grow as an artist, to experiment and improve. As a result our style becomes a work in progress.

The elements listed below have been discussed and dissected in countless books and articles. They are intertwined in a painting and cannot be completely separated other than as a basis for study and learning.

Color Palette – As artists, we choose to limit the number of colors we lay on our palette. We choose which warms, which cools, which darks and lights, transparent and opaque, so on and so forth. We will during the course of our career even zero in on brand choice. So, our palette and choice of colors becomes part of our recognizable style.

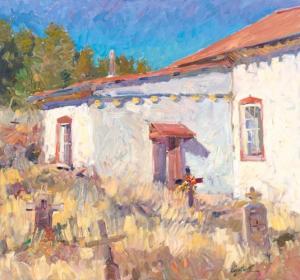

Composition and Focal Point – An artist moves you around and through a painting with the use of darks and lights, pure rich colors and grays as well as where they place the focal point. Edges, texture and brush strokes are crucial in aiding this movement around the painting and to the center of interest.

Edges – The use of edges, soft, hard and intermediate serve to strengthen the composition. Sometimes I think that the pursuit of edges may be the most difficult to master.

Texture – This applies not only to thick/and or thin application of paint, but it also applies to the surface we choose to work on for each painting: from gessoed boards to stretched or mounted linens and canvas, fine weave to coarse weave, etc. I have seen beautiful works painted on copper and on aluminum salvaged from soft drink cans. The surface we choose becomes very much a part of our style.

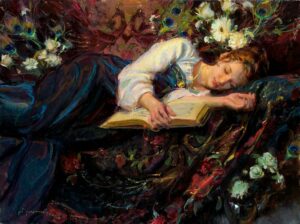

Brush strokes and paint application – Choice of brush, i.e. bristle, sable, nylon, filbert, flat, bright, etc. or palette knife, whether applied thick, thin, broken, and the length of stroke becomes inherent to the artist. This inherent quality helps to mark his style, it is his signature so to speak.

Subject matter – I have often heard it said that there is no new subject matter, just new ways to present it. That uniqueness of presentation is style. It is what differentiates us as artists and as human beings.

In his book, Alla Prima, Richard Schmid tells us: “Do not ask yourself, “What do I see?” Rather ask, “What do I see?” In doing so, we are on our way to developing our own style.