While we are all familiar with the lavish coffee table books, artist biographies, and how-to books which most artists stockpile in their studios like hoarders with empty pickle jars, there are countless books in other categories for the curious art reader.

For the history-loving art reader there are books that trace the evolution of a single pigment: Blue: The History of a Color as well as Black: The History of a Color, both by Michel Pastoureau or The Perfect Red by Amy Butler Greenfield. You will never take your colors for granted again. Instead, you will be grateful each day in the studio when for example, using alizarin or scarlet that you are not in Mexico in 1560, laboriously scrapping tiny cochineal bugs from prickly pear pads.

For the true-crime-loving art reader there are books that read like fast-paced thrillers. Two art forger tell-alls approach the forgery challenge from opposite points of view: In Caveat Emptor (Buyer Beware), Ken Perenyi reveals his methods to create as perfect a fake as he could. You’ll forever be skeptical now of every Butterworth yacht painting appraised on Antiques Roadshow. Read along with him about the day he accidentally figured out how to fake the unmistakable green florescence of centuries-old varnish when seen under a black light.

In Provenance by Laney Salisbury and Aly Sujo, the mastermind’s plan was to use fabulous faked provenances to pass off often sloppily painted copies of modern paintings by Giacometti, Graham Sutherland, and Ben Nicholson. This London con man went so far as to corrupt archived catalogs by inserting made-up pages with photos and information about the fakes. The Forger’s Spell by Edward Dolnick, chronicles a frustrated Dutch artist who faked Vermeers and then had the nerve to sell them to WWII Nazis as they plundered their way through Europe. Perenyi claims the Dolnick book inspired him. Take all the tales with a grain of salt; after all, the authors are professional con artists, but riveting reading it is.

The Monuments Men by Robert Edsel details daring art rescues during WWII. The George Clooney movie version is due out in early 2014. Other Edsel books: Saving Italy and Rescuing Da Vinci.

The Lost Painting, The Quest for a Caravaggio Masterpiece by Jonathan Harr is the true story of a Caravaggio discovered by a museum art restorer in Ireland at the same time a University of Rome graduate student began tracing it from its first recorded appearance in a dusty Italian archive.

The Art Detective, Fakes, Frauds, and Finds and the Search for Lost Treasures is by Phillip Mould OBE, a British art expert who appears on BBC’s Antiques Roadshow and Fake or Fortune?, a London- based show about authenticating antique paintings.

The true 1990 story of one of the world’s biggest and yet unsolved art thefts is told in The Gardner Heist by Ulrich Boser. Still missing in Boston: several pieces of Degas, a Vermeer, and two Rembrandts, including Storm on the Sea of Galilee. Empty frames hang on the wall of the museum to this day. Robert Wittman discusses numerous crimes in Priceless; part of his career was spent on the FBI Art Crime Team.

There are several books about the life and mysterious 1934 disappearance of American artist-adventurer Everett Reuss. Last seen in the Utah canyon lands at age 20, Ruess was acquainted with Ansel Adams and Maynard Dixon, but his solitary search for beauty ultimately was his undoing.

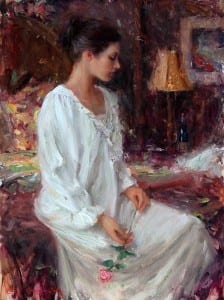

For behind-the-scenes loving art readers, there are two books that explore the surroundings of single paintings: Strapless by Deborah Davis deals with John Singer Sargent and Madame X, who in real life was Louisiana-born Virginie Amelie Gautreau and Lady in Gold by Anne-Marie O’Connor chronicles the creation of Klimt’s masterpiece, Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer.

Winston Churchill wrote Painting as a Pastime and tells a hilarious tale about his first dramatic confrontation with THE BIG EMPTY WHITE CANVAS. He says, “Just to paint is great fun…Try it if you have not done so – before you die.” His work is on display at the Dallas Museum of Art and in the studio at his home, Chartwell, near Westerham, Kent.

For the mystery-loving art reader, there is In the Frame by Dick Francis. Francis is known for his series about English horse racing, but here he incorporates a horse painter and a fake Sir Alfred Munnings. Another of his books, To the Hilt, features an artist living in Scotland.

Masterclass by Morris L. West intertwines two stories – one of a brutally murdered Manhattan artist and one of an unearthed Italian masterpiece. Double-crosses, commissioned fakes, Swiss bank accounts, and international art dealers abound. Chasing Cezanne by Peter Mayle (A Year in Provence) is a fun art romp from France to the Bahamas.

More art mysteries include The Art Thief by Noah Charney and The Art Forger by B. A. Shapiro, which is inspired by the Gardner heist.

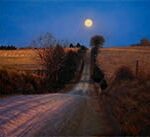

For the romantic, fiction-loving art reader, a personal favorite is The Shell Seekers by Rosamunde Pilcher. A three-generation saga set in England and the Spanish island of Ibiza, The Shell Seekers describes a fictional painting of the same title done on the beach in Cornwall, obviously inspired by the Newlyn School, an art colony established in the early 1880s near Penzance. Real artists there included Lamorna Birch, Elizabeth Forbes, Stanhope Forbes, Laura Knight, and Alfred Munnings.

The Swan Thieves by Elizabeth Costova is also delightful: a modern day obsessive painter unlocks the secret surrounding a fictional female Impressionist’s abandonment of her promising career. Contains star-crossed love, stolen letters, and a painting that makes it all clear when you know how to decipher it.

Vermeer fans will enjoy The Girl With the Pearl Earring (basis for the movie) by Tracy Chevalier and The Girl in Hyacinth Blue by Susan Vreeland. The latter traces a fictional painting’s journey through the centuries.

A graphic, dramatic description of a fictional painting is found in Alexander McCall Smith’s 44 Scotland Street. A portrait painter set up a large canvas to paint a “tiny, crabbit man, (from the Wee Reformed Presbyterian Church [Discon’t]), sitting there in his clerical black suit and staring with a sort of threatening disapproval.” The artist found himself sketching in a “tiny portrait, three inches square, right in the middle of the big canvas…a picture which set out to express all the sheer malice and narrowness of the man…I had boiled down his spirit and it came to a tiny half-teaspoon of brimstone.”

They’ll sit in a golden chair

They’ll splash at a ten league canvas

With brushes of comet’s hair…”

If you prefer happy endings, skip over The Painter Chap by Robert Service (of Yukon fame.) The Painter Chap starts with despondency and despair over his daubs and quickly sinks to knives, a hissing gas jet, and a sad goodbye to Paris. Nude Descending a Staircase by X. J. Kennedy cleverly mimics the painting by Marcel Duchamp with words,

A constant thresh of thigh on thigh –

Her lips imprint the swinging air

That parts to let her parts go by…”

Rory Ewins at speedysnail.com has even composed a group of limericks about famous artists like

Michelangelo, artist of feeling,

Is known for his Vatican ceiling:

The Pope saw some faults

In its featureless vaults

And said, “Paint over that, Mike – it’s peeling.”