One would need to have lived in a cave, isolated from humanity, to have not heard of Roger Dale Brown. In a recent article in Nashville Arts Magazine, Brown is recognized as the ‘go to’ guy of the South when it comes to teaching plein air painting.

I’ve heard of the thoroughness and excellence of his teaching for some time, for he has been a favorite instructor for several years now with the Dot Courson hosted painting workshops.

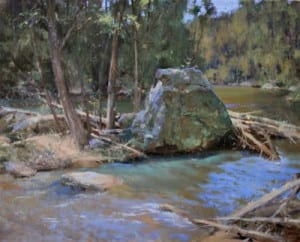

A resident of Franklin, TN., Brown credits historical master artists, John Carlson and Edgar Payne as strongly influencing his belief that plein air painting is an essential element in being a great landscape painter. He is able to capture the emotion of a scene by drawing on his knowledge of painting and dedication to fine art.

He really didn’t pursue art as a career until 12 years out of high school, but he has certainly made up for his late start through study and lots of hard work…much of that outdoors…en plein air.

His spiritual journey in itself is a pretty interesting story and will be covered in a later blog. For now, I know you will appreciate hearing from Roger Dale Brown on the subject of art.

I feel so blessed to be able to have a career that I truly enjoy. I also enjoy passing the information on to other people. There is a sense of accomplishment for me to see the progression of a student. I love sharing and as I progress there is more and new information to pass along. To be able to share and talk and discuss scenarios with aspiring artists and get them excited about the process of art is invaluable.

What makes a good teacher?

Being able to break down a topic into its simplest form and build it back up in an understandable explanatory way, both visually and academically.

I try to explain things from a student’s perspective at each student’s individual level. I put myself in their shoes, and remember when I was at their stage. That makes it easier not to talk over their head, and to explain situations at each unique stage.

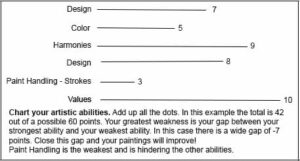

I love to figure out the best way to teach a student. Understanding strengths and weaknesses of individuals and understanding personalities help. I love to figure out the best way to impart a sense of accomplishment to each student.

In a workshop scenario you have to rely on impact…meaning, there are many different ability levels of students. In a time constrained workshop you do not have the luxury of teaching drawing, design, color theory, etc. It is futile to try to teach this in a 3-day workshop setting. I have good success with verbal teaching, coupled with visually showing the students what I am talking about, and then giving them the opportunity to implement it themselves. My goal is that they will take that information and seek knowledge outside the workshop. Helping the student to see certain important facets of the academic process, such as different types of light, simple shapes and the values of those shapes, seeing atmospheric perspective, simple drawing of shapes are all important elements that can be shown in a class with significant success. It gives them a base to learn from inside the class and out. It gives them a success which in turn creates passion, and passion goes a long way in the learning process.

Understanding individual needs so I can work within the capabilities of each person is helpful for the advanced student since they need instruction at a higher level.

When I lecture, talk through a slide show or give a demonstration, I don’t hold back information for the sake of the beginning student. The beginner or intermediate student will not understand a lot of the theory or logic presented, but they will grasp what they need at the time and it will introduce them to terms and knowledge they can refer back to when ready. This way, all levels are getting proper attention.

Do you feel you received sufficient training to be an artist?

I don’t know the answer because I’m still training. I think the answer is “no”. I never had formal training and have worked extremely hard gathering as much knowledge as I can. I hate the phrase “self-taught”. I don’t think anyone truly is. I have taken workshops and have had very good mentors and I am close to some excellent artists that help me. I am in a perpetual state of study and learning. I think it is a never ending process in one form or another. I will always strive to achieve more…then one day, I will die.

What part has plein air painting played in your development as an artist?

It played and still plays a huge part. Knowledge proceeds execution. Being able to see the nuances of nature proceeds painting them. Sight has to be developed. You teach yourself to do this by going to the source and replicating natures subtleties.

What qualifies as a plein air painting?

I think if you go outside with the intent to paint, study, or complete a painting…it’s a plein air piece. If you have to work on it inside to correct a few things or make it a better painting…it’s still a plein air painting. I do not believe in percentages, as in 80% plein air. That is politics that has no place in the art world. No professional artist raises an eyebrow or questions whether you tweak a painting inside. That is petty and unworthy of their time. The only thing that matters in the long run is if it’s good or not. Personally I don’t believe in genre labels. You’re either a good painter or not, whether it’s portrait, figure, landscape, or still life. I believe in being an artist for all it’s worth…

What is your view of the current plein air movement?

I think it’s good. It draws attention to representational art. I believe anytime you paint from life it is a positive step and a great teaching tool. It helps teach us to see as an artist needs to. It has introduced new collectors and buyers to the art market. Its created a new vibrancy in the art community. All in all, it leans more to the positive than negative…but…

I do think there are drawbacks. I think its been bad for the perception of what good art is to both aspiring artists and collectors. There are some great artists that do an exceptional job painting on location, and there certainly needs to be room for every level of painter, without question. I think the issue is what is being advocated as good work. There is a lot of mediocre work being passed off as professional quality. In turn this hampers the artist because they are being told on all levels that their work is great. So they stay drunk and stagnant with praise, hampered in the learning process.

With that said, I’m being hypocritical because plein air is the way I started and I wasn’t very good. Years ago, when I first started painting and was so excited and passionate, I threw myself into the “art world mix”. In retrospect, and in my opinion, too early. Luckily, I had good mentors and started to mature in my understanding of art, coming to see the “error of my ways”. I took a step back and did what I needed to do to further myself as an artist. I started to study and became a student of art…and I will continue to be a student for the rest of my life.

Is it necessary for you to continually discover new locations to paint in order to stay inspired?

I always have places that are special to me…those places never get old and I feel closer to God in these spots. These are comfortable places I submerge myself into, exploring the layers of culture, history, and beauty. I feel that eventually my paintings will translate the depth of those areas. I do like the exploration and discovery of new places. The enigma of a new location has a pull on my spirit that no other element in art can produce. The sheer excitement of the exploration and discovery of a new area can produce mountains of new material to produce artworks. For my temperament, it is important to discover new locations.

What do you hope to communicate through your work?

I try to create art that intellectually engages the viewer with a positive narrative. I want to evoke an emotion and give the viewer enough information to set the tone, but not spell out everything. I want the viewers imagination to work, and let them come up with their own conclusions while directing them to certain areas…interactive art.

Do you have basic rules of composition that you adhere to?

I can see merit in many different theories. There are many ways to approach a painting and they are all the correct way. Artist’s throughout time have come up with their own way of putting into words why and how they create. It is their description of what they see, feel, and do…put into words. One artist might have a different way of describing than another, but they are all trying to get to an end result, which is to make a good painting. I do adhere to some basic rules of composition, but I am not critical of other views if they produce good results.

What is your major consideration when composing a painting?

I look at the whole of a scene that intrigues me, then I lock in on something. I find something to grasp…a focal point. It can be something as simple as the light hitting a tree or colors that complement each other. I then can mentally work what’s around the focal point into a design of darks, lights and color as I see fit. I always bring the landscape to its abstract and work with simple shapes and their value. I break the scene into a dominate color and its complement, or even simpler, into thinking of it as a warm or cool dominate. I visually compare values. For instance, I may compare the lightest part of the tree foliage to the sky, or the darkest accent under a rock to the surrounding ground or water. The “art of comparison” is important in capturing the essence of your scene. I understand that my sharpest edge will be in and around the focal point, but the rest of the scene’s edges are very important and have to be considered also. Sharper edges tend to be in the foreground while getting softer as the landscape recedes or form turns.

How thorough is your initial drawing?

I don’t necessarily draw the scene out. I carve the scene in with shapes of value, after laying in washes for my initial color composition. The proportions of the different shapes in a scene need to be accurate in order to make the scene believable. I think drawing and value are neck and neck as far as importance in the painting process.

Describe your typical block-in technique.

I typically do not draw the scene. I start with washes; sometimes with earth tones; sometimes monochrome; sometimes with complements. Although there are situations, with some particular scenes, that I will draw and use no undertones. I do whatever I feel is the best to capture the essence of that moment. The one constant is that I always bring the scene down to its simplest shapes or abstract shapes. This is the starting point for the block-in. For example, if I am painting a lake or a group of trees, they each become one large pattern with a general value. This is my platform to start creating from. As the painting progresses, I paint within these abstract shapes keeping the values close, so that the original shape always retains its identity.

Do you let the subject determine the concept of the work or do you create the concept and use the subject only as the starting point?

I use the scene as a platform to develop an idea from. It evokes a mood and sets the tone, but we are all creative and to be too literal with every aspect of the scene deprives the viewer of your unique vision.

Manipulating the scene to create a better composition has been done for centuries. Strengthening certain aspects of a scene, while playing down others, is the beauty and genius of Sargent or Schmid’s work. Creating the essence of the scene by being free to create is critical for a successful painting.

Whistler once said, “An artist is known for what he omits”.

How do you decide on a dominating color key for a painting, and how do you maintain it?

Part of my initial analysis of a scene is to simplify it into a dominant color and a subordinate color; the subordinate is always the compliment of the dominant. Nature gives it to us, we just have to look for it. Defining these two principal colors helps me maintain the mood and harmony I want in the painting…this is not to say there are not other colors in the painting, but these take precedence.

There are instances, such as early morning and late afternoon, when there is a hue cast over the scene as a whole. It is like a filter of a particular color held in front of your eyes (rose colored glasses come to mind). In this case, I sometimes use an analogous color system to better capture the moment. I define the hue I’m seeing and then use adjacent colors on the color wheel to paint the scene. Toward the last quarter of the painting, I will introduce the complements (opposites on the color wheel), or I might glaze the painting at the end, to reinforce the cast of light and color in the scene.

What are the key points one needs to know when creating a true sense of atmosphere?

The power of observation, and the science of art. Knowledge precedes execution. If you know that values, color, and edges change according to atmospheric conditions, you are better able to see it when you’re in nature. If you can see it, you will eventually find a way to paint it. You can only paint what you’re able to see.

What are the main problems encountered when translating a field study to a large studio work?

I don’t view the field study as a miniature studio painting. My field study is one piece of information to be used in the studio. Although I have brought some field studies to completion, most of the time it is not my intent. My intent is to be satisfied with the field study and try to get the best painting and most information I can. I don’t want the pressure of thinking I have to take a field study to completion. I prefer the freedom of exploration. The result of solid foundational application coupled with exploration allows for more unpredictable elements in the field studies that I might be able to use or draw from in the studio.

I approach a studio piece with more purpose than an outdoor piece. My objective is to create a studio piece that evokes the mood of the scene, not a replication of it. If I tried to paint the studio piece exactly like the field study, I would fail. Usually it will not translate into a bigger format. It’s a guide, just like a photo, a drawing, or narrative of the scene. In the studio I have a completely different mentality, a completely different arsenal of tools and techniques, a completely different time frame. I have the tranquility of my own space and the time to work through problems and produce the desired affect of the scene.

Think of it in terms of a writer who wrote a 50-page narrative of a story and wanted to make a novel. The story is there in the 50 pages but the novel has to have more information. The writer has to put more into the story, build each character, expand each aspect and create more sub-stories within the main body of the novel to make it complete and interesting.

What part does photography play in your work?

I like to use photographs to jog my memory, to put me mentally back in an area, as a reminder. I think gathering information is key to having a more successful painting. Knowing and understanding your subject helps the photo reference work. When I am on location I try to explore the area, not just the object. I walk around and study the scene up close, how the light falls on it, around it and behind it. I study the culture of the area. I really absorb the moment. Sketches, drawings, descriptive words all help in creating a studio piece. By gathering all of the information possible, I am able to fill in gaps that the photograph leaves out.

What colors are most often found on your palette?

Although I shift colors in and out of my palette, I do have colors that can always be found on it. I use a split primary palette with a few friends…Titanium White, Cadmium Lemon, Cadmium Yellow Medium, Cadmium Red Light, Quinacridone Rose, Ultramarine Blue, Cobalt Blue, Cerulean Blue, Indigo Blue, Burnt Sienna, Raw Umber…

I do not use a green because when I do, it becomes the dominant color in all the greens in the painting. I mix the green for the specific area I’m focused on. This insures a variety of greens…key to a successful painting in spring and summer.

How does one find their individuality as an artist?

I think your individuality finds you. I often hear a student ask, how do I develop a style or how did you get your style? My answer is, “don’t worry about it, just paint”. Painting is a process and you should not get caught up in developing a style. You will restrict your ability to explore if you try to force or copy a style. It will lead to formulating your work, which you don’t want to do. Your unique voice will develop naturally. Your spirit and individual personality will show through in your work if you just paint. That is obvious if you have ever been with a group of artists painting the same scene. None of the paintings look the same.

If you could begin all over again, knowing what you know now, what would you do differently in developing your career?

Start more with the academics. Drawing is an essential part of the growing process of an artist. At the very least it teaches us hand eye coordination. It takes what is in your head to the canvas or paper. It also teaches us the power of observation…the power to see. Getting a late start in life, I have always felt an urgency to develop my skills…and I honestly enjoyed the challenge…but in retrospect I feel I could have worked harder on academics.

Thanks Roger for a very interesting and informative interview. Your honesty and time are sincerely appreciated.

Roger Dale Brown website

Dot Courson Workshops