Interview notes by Elizabeth Robbins

Artists eagerly poured into the lecture room to hear what Scott Eubanks (Gallery Russia), Scott Jones (Legacy Gallery), and Beth Lauterback (Scottsdale Fine Art Gallery) had to say about Portfolios and getting into galleries.

In our modern age of new methods for presenting our paintings; this group of experts gave us a window into their world of submission expectations.

In our modern age of new methods for presenting our paintings; this group of experts gave us a window into their world of submission expectations.

Galleries are swamped with submissions, so artists, do your homework! Find out if the gallery that you desire to be in actually is a good fit for you and your work. For example: Legacy Gallery averages 248 submissions per month. Unfortunately, 95% of these submissions have no idea what kind of work Legacy Gallery sells. Match your subject matter, your pricing and your style to the kind of work that the gallery actually exhibits. Then, be a salesman, sell yourself to that gallery.

Be considerate of the gallery. Don’t walk into a gallery without an appointment and expect them to drop everything and look at your work. Use a portfolio to present your work. The type of portfolio doesn’t matter, digital or print portfolio, although all three of these galleries prefer e-mail portfolios. Whether you show a variety of subjects or just one, your portfolio of images is as good as the worst piece shown. Be sure to show only your best. Galleries are first looking for standout art, and secondly, your bio, good shows, publications in magazines, and competitions. Likewise, they are disappointed if only one piece is strong. They will be looking at your work to see if you consistently produce good quality art that sells. Need they remind you, they are in the business of selling paintings? Their wall space is valuable and they need to move art. It doesn’t matter if you can paint in all mediums and many subjects. In your portfolio, if you do offer them a single medium and a single focus, it is easier for them to see how your work will fit into the gallery. It will tell them if and how they can sell your work.

Be sure to check each gallery for their specific format for submission then stick to those guidelines. It is not about the packaging of the portfolio; it is all about informing the gallery of your best qualities, such as:

Education: Whom did you study with and with what program.

Web site: This gives your work a presence and links to the gallery. In no way should you work in competition with the gallery for sales. Your web site should work jointly with the gallery to create sales for you. Be a partner with your galleries, include links to their web sites.

Competitions: Only include the big shows, not the small shows (no county fair awards, please) and especially not the shows that you entered but were not accepted.

Publications: Articles are great, but not necessary if your work is strong. If you get an article or two, excellent, but in the meantime, put out press releases on your work and your awards.

Images of Paintings: Show only your best paintings with a variety of compositions that will exhibit your strong points.

Personal Rapport: Any gallery that is considering bringing you into their stable of artists needs to feel comfortable about working with you. Are you easy to work with, forward thinking, and creating your own opportunities in your career path? Don’t tell a gallery that you are better than “so and so”. That is not the way to approach a gallery.

Timing: Remember they reminded us, that timing is everything and lots of exposure helps the odds. Put yourself out there every way that you can, magazines, shows, awards, web sites, Facebook, Blog, etc. They will notice you. Show them your best painting. Catch their attention. Let them be the judge of what they can and cannot sell. They each have their own client base and know what will and won’t sell in their market.

Rejection: Okay, so you have been rejected from a gallery, pick your self up and try another one. You don’t want to be in a gallery that isn’t excited about your work.

Question : In the midst of this staggering economy, is this a good time to apply to galleries, or should artists wait until the economy strengthens?

Answer: Do it now. Many galleries are looking for fresh ideas to grab the patron’s eye and pocket book. This may be the time that galleries are replacing or adding new artists.

Question: Do you look at all the submissions?

Answer: Scott Jones, of Legacy gallery, says he looks at everyone’s submission and their websites. He looks for that magical quality that grabs him. Scott did admit that after 3 years of looking at the submissions for the Legacy gallery, only two submissions got into the gallery. This last comment created quite a stir in the audience. A wave of discouragement could be felt throughout the room. However, Scott reminded us that he and the other galleries are always looking at many sources for their artists. He has a list of 109 favorite artists that he is secretly watching and always looking for more artists to add to the list. He regularly checks out their web sites and links that those artists have to other artist’s web sites. That is how he finds other artists. It is easy for him to surf the web looking for new and exciting work. He loves Blogs, but not Blogs or websites that are not updates regularly. He watches artists mentioning other artists. It is a wonderful way to find new painters. Other recommendations: Newsletters: example – Clint Watson’s newsletter – one artist vouches for another. That goes a long way. Contests: i.e. win a Ray Mar Contest. Scott is a huge fan of OPA. It gives artists tremendous exposure. He asked 7 artists at the OPA show to be in Legacy Gallery.

Question: Typically how many paintings do the galleries want from artists coming into their gallery?

Answer: Scott Eubanks- six paintings to start off, four paintings to be hung and two more in the back. Beth Lauterbach answered, six paintings plus good photography of each painting. To create a good connection with her clients she also requires a good contemporary biography (don’t dig too deep into your past) and a good photo of the artist.

All three Galleries agreed:

- Do keep sending submissions to galleries

- Keep your web sites current. Only show your best work. Take off your older paintings.

- Enter shows. Win awards

- Get exposure from many sources: Magazines, Facebook, Blogs, Newsletters.

- Don’t get discouraged.

- Look for galleries compatible with your work.

- Persevere. Keep putting it out there

- Seek a gallery that is wild about your art, they need to fall in love with it.

- Seek a gallery that is run or owned by someone you can trust and is enjoyable.

One of the tough jobs being an artist is that you must find people that share your love of subject matter and style. You must be successful both at painting and also at finding those people that love what you paint.

In closing, for those artists already in galleries, these three galleries all had final words of wisdom!

Question: What if an artist is doing all of the above, but the public isn’t buying his/her paintings?

Answer: Here are some points that Scott Eubanks gave us to consider why art doesn’t sell (besides the poor economy):

- The painting is not as good as originally thought.

- It is over priced. What is the actual track record for that artist’s work.

- Same subject over and over

- Bad choice of subject matter.

- All the paintings from one artist look alike.

- Perhaps the gallery that your work is currently in, but not selling, is not helping you sell the art. Perhaps the gallery itself doesn’t have enough exposure.

- Work your craft, perfect your skills. Climb to new heights.

- Carefully consider your price and increases based on performance.

- Choose subject matter that appeals to the clients in your galleries.

- Find your uniqueness, build excitement in each painting.

- If your gallery isn’t a good fit and you are not selling, look for another gallery that is a good fit for your paintings and you.

- Don’t ever compete with your galleries, they are your business partners. Take good care of them.

- Connect your work to your galleries.

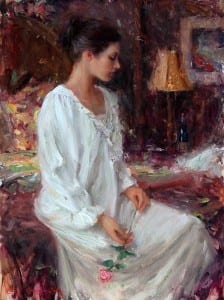

- Take your older paintings out of your current galleries and replace them with uplifting paintings. Scott Jones called them “Prozac Art”. There is enough stress in everyone’s lives, people are needing and buying peaceful, pretty art that soothes their minds and souls.

Most of all, Beth Lauterbach concluded, “What you do well, continue to do well. If you are selling, keep doing it”.

We all left the room inspired!