How are you feeling today? Tired? Inspired? Brave? Beaten? As a painter, are the voices in your head your piper or your punisher?

Curiosity is seriously cool…

“Curiosity killed the cat!” So, did curiosity actually kill the cat? Not that I’m aware of. The saying is floating around like a dust bunny under a couch in pretty much everyone’s sub-conscious having a party with these guys: “Don’t be curious!” “Curiosity will get you in trouble!” “Curiosity will be punished!” “Be curious and you could die…the cat apparently did!!” These are the thugs it runs with. They’re lurking there and live to make you cave in to creative paralysis. “Don’t try that new idea, technique, subject matter. It might not be accepted. It might not work out. It might not sell. It might not win a ribbon. You might embarrass yourself! You might…FAIL!!!” The voices get more shrill until we’re slump-shouldered, our face in our hands and that spark of an exciting, new, utterly original idea that flitted through our brain has run for the hills.

When we were two feet tall, instead of being congratulated for our amazing creativity we were likely ‘domesticated’ – trained to be compliant. Having figured out how to open the kitchen cabinet doors, use the shelves as a ladder, do a rock climber worthy move to get on the kitchen counter and get a cookie out of the cookie jar from top of the fridge likely got us a swat on the bum rather than the applause it deserved!! Curiosity is BAD still lurks like Gollum under a rock in our brain.

Crumbs are seriously crumby…

Be on the watch that you don’t barter away your curiosity and the chance for adventure and artistic progress for crumbs. When we move off our artistic vision and worry about what a judge will like, what Aunt Mildred might scowl at, what we see other painters getting pats on the back for, what worked for us last week, what is safe – we may have just slammed on the air brakes of our own progress.

The likes of Courbet, Manet, and Pissaro didn’t move off their vision and race each other back to the land of safety and acceptance when they were rejected from the 1863 Paris Salon. They kept pushing the envelope answering over and over their own versions of the question, “What would happen if we tried…”

Be the most curious of cats…

The phrase “Curiosity killed the cat.” was originally “Care killed the cat.” Care as in ‘worrying’. So apparently the worried cat didn’t fare so well but the curious cat is quite alive!

Care deeply but don’t worry. Care motivates. Worry paralyzes. Care about your vision. Care about your progress. Care about the joy of creating. Even care about the craziness of the struggle. But, don’t worry. Don’t worry if your sincere efforts for the day missed the mark you were shooting for – you can try again tomorrow. Don’t worry if a judge passes you over. Don’t worry if Aunt Melba scowls at your recent effort. Congratulate that Indiana Jones part of yourself that has the courage to explore.

As painters, curiosity is our rocket fuel! Worry is our kryptonite!

Tomorrow, roll out of bed. Try something new! Handle paint a different way! Paint an amazing passage and then scrape it off just to prove you’re the master of the ship! If you paint with bright colors, try painting the nuance of grays. Pick up some sticks or rocks and lay them next to your brushes. See what kind of interesting marks they might add to your canvas. If something is starting to feel easy go paint something that feels hard.

When we try something new we never fail. We’ve succeeded in finding an answer to the question, “What would happen if I tried…?” We found out what may be useful. What may not. We may stumble on something amazing that isn’t useful in the moment but we can stash in our toolbox for later.

You get to choose the voices in your head. Follow the Piper. Delete the Punisher. Be curious. Try new things! Fling yourself off the side of the pool with abandon and do a flailing belly flop. Might sting a little but you’ll paddle back to the side of the pool, find the beauty in shaking yourself off like a wet dog and… you’ll want to go try it again!

Exercise that cat…

Here’s a personal challenge, which is actually pretty fun. I predict you’re going to surprise yourself. If you’ve recently painted something that you’ve gotten a bit of praise or an award for – try something that’s the polar opposite and see if you can create a more powerful painting than the one that just got the applause!

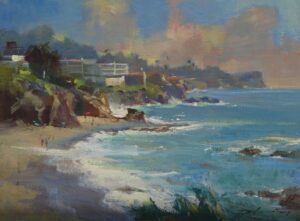

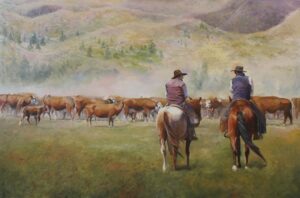

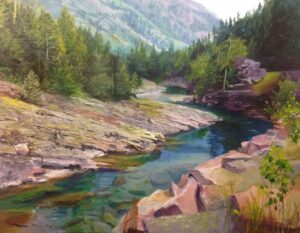

I’ll leave you with an image, ‘Havana Grays’, that originated by doing exactly that. An appreciative person stood next to me in front of a painting I’d just finished. They stared at it, turned to me with delight and with all earnestness said, “It’s sooooooooo detailed!!!!” I mustered my very best thank you ever so much smile while inside I was figuratively beating my head against my paint palette. Wowing someone with technical ability wasn’t on my goal list for that day. Inviting them to feel something was. I set out a challenge for myself. Learn when less can indeed be more. My intent for the next morning’s studio session was to answer the question, “What would happen if…I attempted to create a painting that was stripped of absolutely everything except that which was essential to communicate the mood, and my memory, of that moment in time?” ‘Havana Grays’ was the painting and it immediately found its ‘person’.

Every morning when we wake up and take up our brushes there is always another question to ask. So, go exercise that curious cat, jump up on the counter and stick your artistic paw in the cookie jar that’s on top of the fridge!

20″ x 10″ – Oil on linen