He shows in some of the Finest Galleries in the country, has won numerous awards and is included in many private fine art collections. He is a Master Signature member of the Oil Painters of America, Plein Air Painters of America, California Art Club, Northwest Pastel Society, Puget Sound Group of Northwest Artists, Northwest Rendezvous Group, and the American Society of Marine Artists. Ned is the only Artist in the Northwest that has been designated as “Master Artist” status with both the Oil Painters of America and the American Impressionist Society. He continues to challenge himself to grow artistically. Ned has been asked to jury Regional and National Art Shows and he loves to teach and share his many years of knowledge and experience by teaching classes and workshops, regionally, nationally and internationally.”

***All Images Contained Within This Video Are The Works Of Ned Mueller And Are Protected Under His Copyright***

Plein Air Workshop

8/18/2017 – 8/20/2017

Plein Air Workshop

10/26/2017 – 10/28/2017

You can obtain more information at:

ScottsdaleArtistsSchool.com

Oil Painting

THE TRICKY BUSINESS OF ART

I’ve been an artist since I was a child. I never knew how not to do it, but being an artist is not the same as being a professional artist. I embarked on this around 2006 or 7. I started to realize that it was my time to do what I had always wanted to do but didn’t allow myself to really pursue. What’s the difference between being an artist and being a professional artist? As an artist you are creative and passionate about what you do. As a professional artist, you are creative and passionate about what you do but you are also in the business of selling your art, for a living in most cases. This may be oversimplifying but you get the idea. There’s money involved and that’s when it gets serious for me. However, making real money for your art can be a ‘tricky’ business.

Trick Number One

The number one thing you should focus on is producing the best art that you can produce, whether it be porcelain dolls, illustrations, woodcarvings, or fine art oil paintings. Learn to do what you want to do to the best of your ability. This is an ongoing process with art. Good artists never stop learning so I don’t believe that you should wait until your art is perfect before you start selling it. For many artists, its never going to be perfect. That is how they come back to the easel or the workbench everyday to try again to get close. I do think there are buyers for art at every level of one’s professional career as long as it is priced right. Pricing is a different topic for a different day but, if you choose to be a professional artist, there are buyers out there for everyone.

Trick Number Two

They have to see it before they can buy it. I know many people who go through magazines and catalogs and say “I paint better than that” or “My friend so-and-so can make better ‘insert type of art piece here’ than that”. Well, are you or so-and-so making sure that people get a chance to see the work like the people that are in those marketing materials? You have to spend money to make money. Spring for the advertising when you get accepted to a show. Run ads in magazines that you respect in your industry. Do a Facebook marketing campaign occasionally. Do something to get your work seen by potential buyers.

Trick Number Three

Treat your business like a business. Art is my profession and it is my 9-5 and bread and butter. I show up every day to do something related to my business. I paint. I photograph the work. I keep my inventory software up to date. I keep my financial software up to date. I keep my inventory stocked. I keep my materials stocked. I know how much art I need to be producing each month in order to keep supplying my galleries and I keep detailed records of where all of my art is at any given time. Plenty of people try to run businesses in any field but if they don’t do these things, they fail very quickly. Just because you are an artist, it doesn’t mean you are exempt from these rules. Get a personal assistant if you can’t handle these things but somebody’s gotta do it.

Here are the quick plugs for the vendors I use: Quickbooks for financial software; ArtworkArchive.com for inventory, customer and show tracking; FineArtStudioOnline.com for my website; Meininger Art Materials for local supplies, RosemaryandCo.com for my brushes, Gamblincolors.com for mediums and varnish; Winsornewton.com for paint; local lumberyard for birch panels. I’ll try other things occasionally but I keep coming back to these.

Trick Number Four through …

Getting into galleries, getting accepted to shows, getting invited to invitationals, etc, etc. These things come after you do tricks 1 -3. The journey is different for everyone so there are some things you may not care about. Things can also change for you on a daily basis and you have to readjust the plan. I know that if you are focusing on 1-3, the rest will become more obvious and easier.

Thanks for reading! I hope that I have helped you in some way. Feel free to comment. I look forward to reading them.

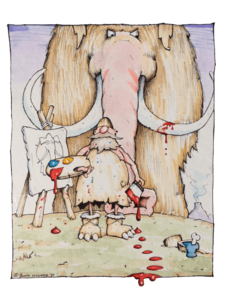

“KWAK AND LUG”

The first artist (let’s call him ‘Kwak’) faced the first dilemma: “How do I price my work?”

The first artist (let’s call him ‘Kwak’) faced the first dilemma: “How do I price my work?”

Kwak was a natty little Neanderthal, not much good at physical labor (and before anyone shakes a spear at us, we recognize those researchers who attribute the bulk of his work to his unsung partner ‘Wampat’), but…be that as it may: Kwak had just finished a fine head study of the Old Chief’s mastodon and was at a loss what to charge. Kwak turned to his best friend (who was even less adept at labor––but dreamed of opening a gallery), and asked him:

“So, Lug––be honest: How many seashells can I ask for this?”

Lug (a little miffed at being asked to ‘be honest’––for he was invariably honest) replied: “It’s not what you can ask, Kwak––it’s what you can get. Old Chief doesn’t like to part with his seashells.”

Well, thought Kwak: Tell me something I don’t already know.

Sensing Kwak’s disappointment, Lug said: “What if I go to Old Chief? Would you take ten seashells for it?”

“Well…” Kwak was hesitant.

But Old Chief was to be avoided if at all possible. He was a scary old guy, always asking Kwak when he planned on doing some real work.

Lug sweetened the pot: “Look––if I can get more, I will. I don’t want to leave any seashells on the seashore any more than you. We’ll split whatever I get, down the middle: sixty/forty. How’s that sound?”

“Pretty sweet,” Kwak agreed.

Now Lug was just as afraid of Old Chief as everybody else, but seashells are seashells. He caught Old Chief at an opportune time: just back from the seashore–– and loaded with seashells.Lug pointed out what a fine rendering Kwak had done; his work on the mastodon’s tusk was exquisite: worth ten seashells by itself. He also mentioned the rarity of the piece (for it was, indeed, the first piece of artwork). In Lug’s eyes, that doubled its value. Finally, lowering his voice, Lug said he hated to bring this up–– was very apologetic to Old Chief––but (full disclosure) the young chief in the next valley, Eats-Seashells-For-Breakfast, had expressed an interest in Kwak’s mastodon…

“But that’s my mastodon!” Old Chief shouted and sputtered. He was outraged.

“Yes Sir. You are quite cor-rect. Though, act-u-ally, in this case…er, by, um, tribal custom, Sir––Kwak has the rights to the image…but that is stuff for a future blog, and nothing you need worry about today…”

Old Chief grumbled…

“Eats-Seashells-For-Breakfast wants it, eh?” (Old Chief was Canadian on his mother’s side) “Well, Lug, you are a thief, but I’ll give you thirty seashells for it, and not a single seashell more.”

“Will that be cash or credit, Sir? And…um, sorry––we must remember the sales tax. We can’t forget Big-Chief-On-The-Mountain.”

Lug was very proud of his day’s work. He had done a favor for his best friend and got him some extra seashells to boot. He also had enough shells to open that gallery. He knew just the spot…right on the path to the seashore.

Kwak too was proud of his day’s work. He had gotten Lug to shake some seashells out of Old Chief. No easy thing. His work was now where other Chiefs might see it. True, he had expected ‘sixty/forty’ to be worth more than twelve seashells––he had never been good at math, having skipped school that day––but, whatever, it was two more seashells than he could have gotten on his own.

His wife, on the other hand––for reasons Kwak could not quite follow––was not happy. Not–happy–at–all. She (nee: Wampat Goody-Two-Boots) had never missed a day of school, and was quite sure Miss Google had demonstrated the concept of ‘down the middle.’

Gently, Wampat asked Kwak if he had gotten this agreement with Lug down in writing.

Kwak gave her a blank look and asked: “What’s wr…”

Wampat threw up her hands and stormed out.

How is Art Like Surfing?

14×18 Oil

Try to visualize the waves as trends in art.

Surfers work hard to paddle out. Similarly, artists struggle to learn and find their artistic voice.

Surfers finally get to that sweet spot and catch a wave; those paddling stop to watch them glide by. Similarly, artists still in the water of obscurity see others riding a new artistic trend, yelling, “Here’s how to paint.” Those struggling are growing anxious, thinking “I should be on THAT wave.”

Some surfers ride a wave till it runs out; others get off the wave halfway and struggle back to a prime spot; still others catch a smaller wave halfway to their goal. Similarly, some artists hope they eventually catch a good wave and can ride out an easy career; others see the times changing, and decide to jump off the wave and struggle back to a sweet spot; still others choose a smaller wave halfway out, abandoning the difficulty of the struggle.

It’s an organic visual loaded with metaphor, isn’t it.

The tide that pushes against every artist is the fear that the best things are passing us by. Steven Pressfield personifies it as an enemy called Resistance in his book “The War of Art”. He says, “Resistance has no strength of its own. Every ounce of juice it possesses comes from us. We feed it with power by our fear of it. Master that fear and we conquer resistance.”

One example of an artistic trend is the American “plein air movement”. It’s on a bell curve just like everything else. It will change (already it has different regional expressions), and most likely it will, like all waves, sink in the ocean to manifest another day.

16×20 Oil

Fortunately, there’s a bigger wave building that we can be excited about—it’s the interest in art in general! There’s still a ways to go, but the swell is evident. It’s a great time to be an artist. It’s a great time to be studying and growing. It’s a great time to teach. Today’s students of art are the future art collectors. There’s an awesome set of waves coming.

The more I’m in this career, the more I feel this growing wave. I want to be out front.

If you feel it too, here’s what I recommend: know art history intimately; don’t stop studying it, and be respectful of ALL OF IT. The history we’ve been dealt is a proverbial pearl of great price. We’re not innovating; we’re standing on tall shoulders. There comes a time to wean yourself from just painting for the “love of it.” It’s something to take seriously. Look to artists that don’t appeal to you on the surface. Read about their lives. Your work will have a deeper look and meaning if you let diverse stories and styles influence you.

Degas and Corot were two artists known for this kind of profound reverence. From the book “Corot in Italy”, it was said that his great accomplishment during his formative Italian journey was to “…fuse the empirical candor of outdoor painting with the pictorial rigor of the classical tradition.” He was respectful of the traditions he came from, and yet, before nature, he looked with fresh eyes and produced work way beyond his time.

In the book Degas by Jean-Jacques Leveque, it was said, “Like Manet, he (Degas) was torn between his reverence for the past and his visions of the future.” While others like Monet and Pissaro were dismissive of the romantic traditions in the Parisian art scene, Degas was respectful of it and payed homage to it, and yet fused it with his growing love of the Impressionists broken color. He implored his peers to temper their reactionary speech.

This is important to note because some artists and art movements today want to react dismissively to the art movements of the Twentieth Century. How will we ever have real conversations with the curators of the avant-garde if we don’t have a healthy respect for what they represent? But that’s a discussion for another time.

[One way you can catch this vision is to join me and Jason Sacran in Italy the summer of 2017 as we introduce you to one of the most influential communities in the world of representational art, JSS in Civita, through our workshop “In The Birthplace of Outdoor Painting”. Go to lasaterart.com/workshops to learn more.]

Let’s get ready for the big wave! HANG LOOSE my friends.

speaker and demonstrator for the 2015 Plein Air Convention and the 2016/17 Plein Air South Conventions. He will be demonstrating at the 2017 OPA National Exhibition.

Where did all the color go?

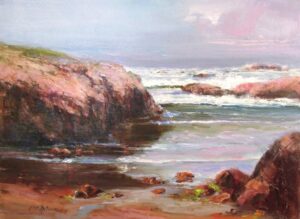

Not this year. After years of California drought, off-shore weather systems were now massing early off the coast. My favorite location had lost most of its sparkle and all of its high color. I am committed to this location at this point, however.

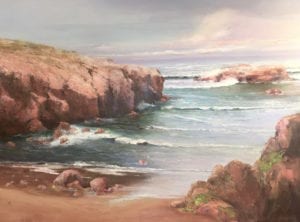

The next task was to paint my large studio piece. I used the same process as with the Plein Air studies—limiting my pallet, holding very tight with Grey mixtures, then adding color to complete San Mateo Coast.

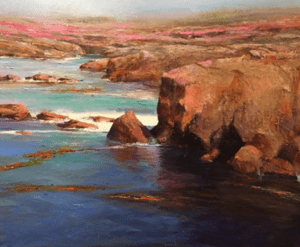

After completing my work for the museum show, I decided to apply the strategy to another painting at a different site. I was especially happy with Point Lobos Calm No. 2 and have since been using the limited pallet with a couple of accent colors for all of my Plein Air work.

I have just received notice that Point Lobos Calm No. 2 has been accepted to the Oil Painters of America 26th Annual National Juried Exhibition of Traditional Oils.

I think I’ll stick with this approach for awhile!