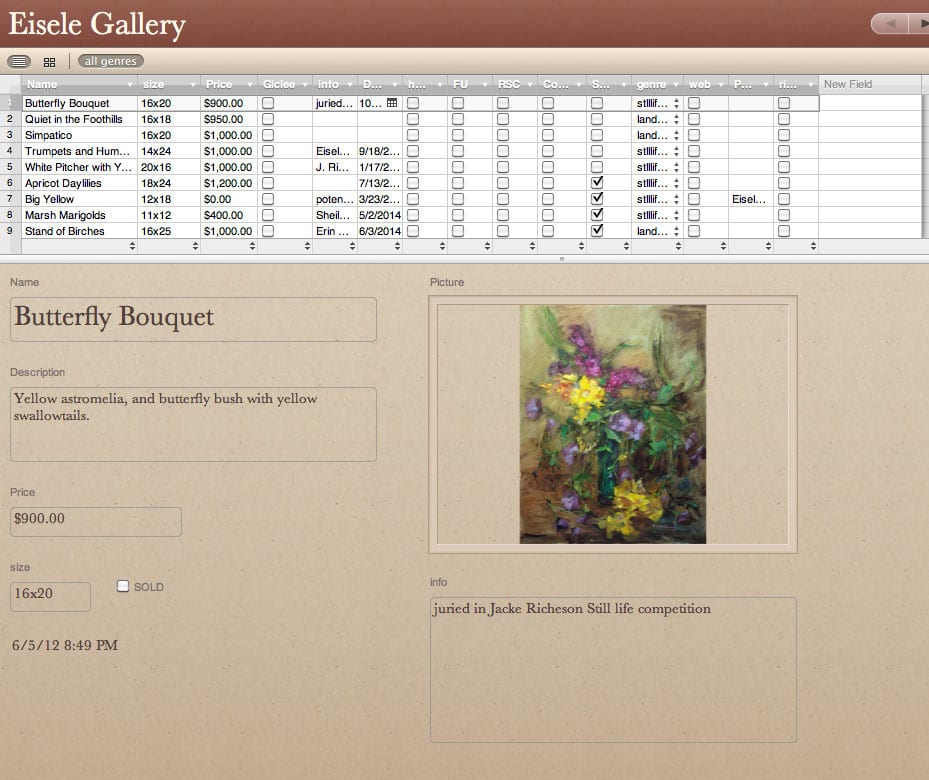

About 8 years ago I purchased an inventory program for my Mac. It has been indispensable. The particular app that I bought is no longer available, so I hesitated to bring it up as the best tool I’ve got for my business, but there are other apps out there that can do the same basic things. Mine is called Bento, but Filemaker is another one that would work. It does require some time to get it set up but the work and frustration it can save over the long haul is well worth the time and investment in getting it started. The inventory program I work with allows me to record all the basic information for each painting..including (my favorite part) a photo of it. I can add categories for customers, for competitions entered, gallery inventory and more. It has the capability to create secondary lists (smart lists) for any specific details (examples…paintings that have sold, or only landscapes,or only paintings showing at Gallery xyz….I can isolate and pull up an entire “show” for planning and all the information is there in a nice concise form.

Inventory gets added as soon as it is completed and all it’s details are filled in size, cost, title,and image along with the date of completion, before I have had a chance to forget it. If a painting sells all I have to do is put in a check mark and the app automatically moves it to the “sold” lists. The best part is having an image of the painting right there available. I have an awful lot of “yellow roses”, “yellow roses with a white vase”. etc…and it’s pretty hard to remember 2 years down the road just which painting was which! It is a life saver!

barbaraschilling.com

Oil Painting

Notan Sketch VS. iPhone 6

“Notan” is a Japanese term referring to exploring the harmony between light and dark. Artists use Notan sketches to explore the composition elements of a scene and the relationship of major shapes. A good Notan drawing simplifies a scene into three values…dark, light and halftone. It also acts as a memory and planning tool that helps the artist focus on essential elements of a scene, draw simple shapes and record important elements should the scene change as weather and sunlight alter a scene.

I was first introduced to the importance of the Notan sketch in a workshop I took with Skip Whitcomb. Skip starts every painting session with two or three quick sketches of the scene. The process takes him about thirty minutes. As part of the workshop Skip required students to do at least three sketches before starting a painting. Since that time I have come across many artists that rely on the Notan sketch process and for years it has been my practice as well.

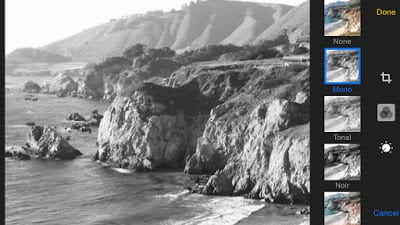

The advantage of a Notan sketch over a camera is the camera records everything in the scene indiscriminately leaving nothing to the imagination. That being said I have come to prefer the camera over the sketch as the smart phone increasingly takes over every aspect of our life. Using the photo app in my iPhone has reduced the time to produce a Notan to a matter minutes rather than a block of time that cuts into painting time.

I recently took the opportunity to produce a Notan sketch and a Notan photo to decide once and for all what my routine was going to be going forward. Below are my results.

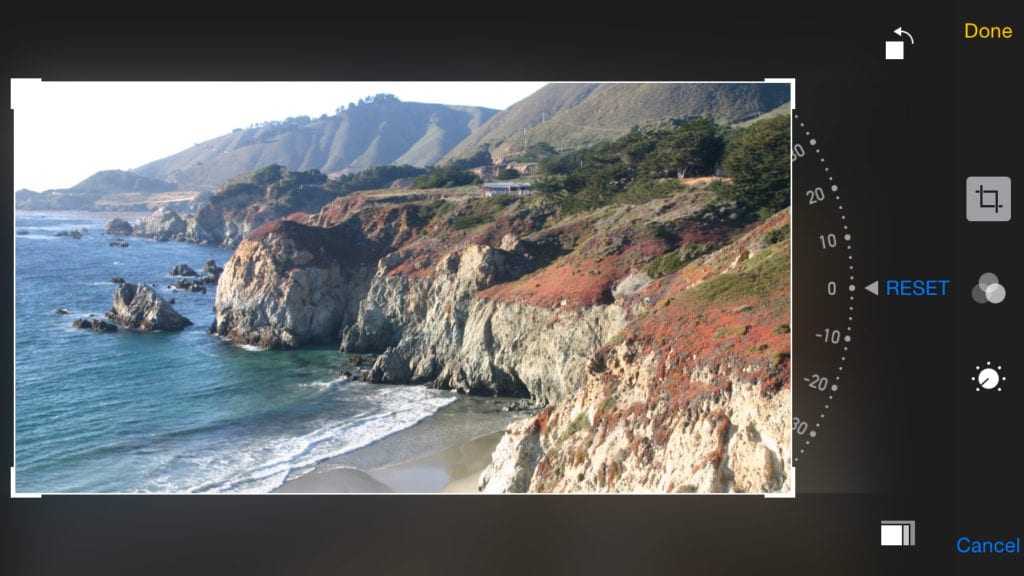

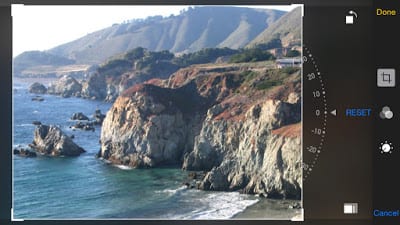

South of Monterrey on the way to Big Sur is this amazing scene, painted by many. On the day of my painting the fog was rolling in and out all day constantly changing the light. The scene was so captivating it was hard to decide what to leave in and what to take out. It was the perfect time for a Notan sketch so by the time I put brush to canvas most of the major decisions would have already been made.

Like many plein air painters my “go to” format is the horizontal on a 9″ x 12″ or 12″ x 16″ panel. I also like the long, narrow horizontal format I use frequently in Texas due to the lack of mountains or anything taller than a fence post. My first inclination was the long horizontal as seen in my Notan which took about ten minutes.

Just for kicks my second sketch was a square format and my third sketch was my usual horizontal.

The whole process took longer than expected because of the fog that would come in and obscure the distant cliffs that I wanted to include in my painting so all total it took almost forty minutes to get the sketches done.

Simultaneously when the sun was just like I wanted, I took a single photo with my iPhone and as the fog destroyed my scene, I quickly opened the photo app

to look at the scene in different formats.

I first looked at the long, horizontal format, cropped it accordingly and saved the image for future reference.

Then I cropped the same photo in the more typical horizontal for a 9″ x 12″ painting. Again I saved it for later.

Then I used the halftone filter to give me a Notan photo of my scene. The whole process took less than ten minutes which is an important consideration when the goal was to produce four paintings this day.

“On the Way to Big Sur” 9″ x 12″ oi/linen

When it came time to paint, the fog became unavoidable. In the end I gave in and included it in my painting, but the Notan exercise was well worth the effort.

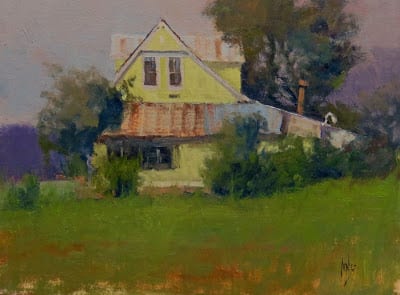

Below is another example of sketch versus photo Notan.

The painting.

There is something that makes me feel more “artistic” drawing Notan sketches before beginning a painting. But at the end of the day, for me at least, its all about evaluating the scene for composition and values and the iPhone provides me the quickest means to an end while also providing me a permanent record. In less than ten minutes I can produce several Notan photos with complete halftone evaluations of my scene and I think it gives me a clearer understanding before I begin to paint.

Getting the Most Out of Your Camera

Just about every representational artist knows the benefits of painting from life. The naked eye can see far more than a camera and constantly adjusts for each lighting situation. Our other senses tell us if it’s windy, hot, cold, and fragrant. All this affects the painting of the scene before us. For some artists, the painting must be finished in the field that day or subsequent days. For others, field studies and photographs are part of process in creating their painting.

The huge movement of Plein Air in the country has given birth to countless Plein Air paint outs, workshops, and new artists. Art suppliers and magazines are selling everything from easels to ad space to feed this new hunger for painting outside. There is a common misconception that “Plein Air” is a style or look. Artist’s for more than 100 years painted outdoors as a means to accurately document real life. Field studies were just part of the process to creating a painting. Zorn painted from life but used photography on occasion to help in the creating his masterpieces. Like a brush, the camera is a tool. You don’t buy cheap brushes, so don’t buy a cheap camera. If you are seen at a Plein Air event with a camera nobody will make you turn in your wide brimmed hat.

In fact, the camera will help you document a new area to get ideas for painting sites. When I attend Paint Out events, my camera is always with me. If I see a great scene with fleeting light that will be gone in 20 minutes, I photograph it. Taking shots panned back, up close, vertical, horizontal, and all around, I write down the time. The next day I come back an hour earlier and paint my block in while anticipating the coming light. This approach works very well because the night before I have viewed my photos and picked the best composition. So when it’s paint time, I don’t get hung up on too many problems. If I’ve been to the same paint out for several years I have lots of photos to look over and go back to those familiar places and have a solid idea to paint. You can waste hours looking for something to paint. In unfamiliar territory, I’ll sometimes use google satellite and hover over areas that might have some possibilities to paint. You can use street view and cyber drive through the countryside. If something looks good I’ll mark it on a map. My years as an illustrator made me resourceful in finding new ways to help in the craft of picture making.

The camera is also very useful when you are visiting a wonderful place for a short time. You can document the area with hundreds of photos as opposed to only having the time to paint a few studies. Back in the studio with no field studies, I must have very high quality photographs and view them on a large monitor. It’s best to paint soon after your photo reconnaissance, so your memory is still fresh and you remember what grabbed you in the first place. I know from experience that my darks tend to get inky and lights get washed out. Your camera’s aperture tries to give you all the values, but misses in high contrast situations. Our eyes adjust constantly while painting from life. So in the studio I need to open the shadows and darken the washed out lights. Color saturation can be gone as well, so I’ll adjust that too, and make sure my canvas is in proportion to the photograph or study. An inch one way or another will change a composition, and you may lose what you set out to do. If I have no field study, I’ll paint one in the studio and work out the problems first. With a complex scene and wanting to combine several photos, I’ll use photoshop and create my composition.

I like to use figures in my landscapes and photography is the only way to record a moving person. Sometimes while painting outside a figure may walk into the scene, so I’ll take a quick shot. In the studio I have the best documentation with a field study and a quality photograph of the figure to create my painting.

When photographing your finished painting it is very important to have a set up where you have diffused natural light and a solid tripod that you can level. Glare can be a common problem and is caused by another light source like a window.

So the camera can be a great tool in your art career as long as you understand it limits and know that nothing will replace painting from life.

billfarnsworth.com

bill@billfarnsworth.com

My Favorite Thing – Lori Putnam

Solvent Free Gel by Gamblin Artist Colors is one of my very favorite things. It is odorless, CLEAR, and thick enough to hold a good heavy paint stroke. It loads well on the brush and I love the way the paint feels when I lay it on the canvas. It is particularly great when using brushes that can support a lot of paint, like extra-long filberts. I began using it while painting in Plein air events to speed the drying time of my paint. Soon I was hooked and use it in my studio work now as well.

www.loriputnam.com

The Pace Race

Like any vital, living thing, the art world is ever evolving. In the distant past, paintings were accomplished in the studio by painstaking application of layers of paint over a period of sometimes years. In the not-so-distant past, the trend toward alla prima painting increased the expectation of completing a piece in a much shorter time span. In the present day, time-lapse videography has made it possible to witness a 3-hour painting demonstration in eight or ten minutes! Now, there’s a wicked thing in my head that tells me I’m incompetent if I can’t paint a decent demo in eight or ten minutes. Not literally but, well, almost literally. The truth is, I’m a slow painter. I want to be a fast painter and this has steadily stolen my focus away from the simple joy of painting. This year I learned that I’m not alone; there’s a bunch of us trying to get faster. It’s a painters’ version of anorexia: you see the magazine cover of the perfect quick-draw painting and look at yourself to see if you’re good enough. You’re not good enough in your eyes so you start starving yourself and exercising and self-destructing, when all along you really were good enough; you were just different! Maybe you need someone to tell you that. Maybe I do, too.

At the end of last year, I decided that I wasn’t fast enough to be good enough to call myself a plein air painter. I set my goals for this year, and my Number One Goal was to learn to be a really fast landscape painter. My training heretofore was exclusively studio and mostly portrait-oriented, and while I’d been painting outdoors for more than a decade (and frankly loving it with an unadulterated love), I’d never actually been taught how to paint en plein air. My plein air works were, in the words of Robert Genn, “unabashed two-steppers.” I would paint as much as I could on site and then finish the rest later, using my mixes, my start, and my reference photos. I hadn’t entered any plein air events because of that, and I have felt more and more ashamed about it. Well, that was all about to change because I signed up for two workshops at the beginning of this year; one with Ray Roberts and the other with Jill Carver.

Both of these great artists and great teachers asked their students what they hoped to gain from the respective workshops and the answers were pretty much the same: we all wanted to learn to think and paint faster in the field: to come to a place and be able to compose a finished painting in our head while we were setting up, mentally Photoshop trees and rocks and rivers in and out and all around a canvas, capture the essence of it before the light changed, be able then to slap a frame on it and win a gold medal. That’s what we all hoped to learn.

Here’s what we all did learn: sometimes what you think you need to learn is different from what you actually need to learn. The gentle admonition from them was, it’s not about speed: that’s asking the wrong question. Jill suggested that there would never be an entry in an art book saying, “Painted between 2:00 and 3:45 p.m., whilst competing against so-and-so.” No, the painting must forever speak for itself and if you can’t paint it well going super fast, slow down. Neither of these painters comes to a landscape with an expectation of coming away with some kind of slap-dash masterpiece. Roberts’ approach was to consider plein air work as fact-finding and idea-catching, making numerous small sketches with an eye toward a studio piece. And Carver’s strategy was to make it less of a hunting expedition (her words) in which you “bag a prize,” and more of a private conversation with a friend. Her approach was very slow and polite; sketching ideas in a book with a sharpie and making notes before her kit was ever unpacked for painting. When she does get her gear out, she often divides up the canvas into two or four sections upon which to paint her response to the landscape. I’ll tell you how this affected me: I felt liberated. Liberated from my own expectations and free to be myself out there.

When I watch great painters paint, they do not ever seem to be in a hurry. Even if they accomplish a painting in a short time-span, they are very deliberate in their application. I felt all warm and tingly when I learned that my hero, John Singer Sargent, might paint and scrape a head sixteen times, so as to ultimately leave a fresh mark that seemed quick and effortless. But even before that, he’d done dozens of sketches. Seeing the plein air studies of another hero, Joaquin Sorolla, was exciting because they were all so tiny and jotty, like the shorthand notes of a writer! When I shared with my husband my new goal to be a fast painter, he said, “You don’t do anything fast! Why would you want to do the thing you love the most fast?” None of these things will sink very far into a hard head.

When Jill Carver paints a place, she has first loved it. Her painting is a poem about it. She has already sketched different versions of it and maybe painted several studies before she approaches the Painting Proper. When she set up for one demo, she situated her canvas so that her back was toward the subject. By doing this, she could only paint whatever she remembered once she was facing the canvas. This is an old Robert Henri trick. It requires a bit of your soul. But it takes a little longer.

Here are some studies done by Jill, exploring the number of values needed to convey a scene, preferring to keep it between three and five. This is one of the ways she helps her students to deconstruct and tune into the scene. Note the way she matches the colors to the values:

While we were working outside, her repeated, disarmingly funny, admonition was, “Paint what you see and keep it simple: after all, this is not rocket surgery.” She encouraged her students to relax and let the scene choose us, let it reveal itself to us; that requires calm and quietude. It is much more courteous and respectful than the smash-and-grab technique that I thought I wanted to learn.

Ray Roberts was working with rapidly changing light because, as luck would have it, we had rare weather blowing through the desert while we were out there, including riotous thunder storms! It was exhilarating to watch him work; he engaged the constantly changing light by constantly changing canvases! I know I would have decided to stay in the studio if the weather were unpredictable like that, but he taught us to move with the weather, to let it speak to us and take dictation so we could report our experience later. Our steno pad was the canvas, 8×10’s quartered, so that we could make four 4×5 inch paintings of the changing light. If he ran out of spaces, he tossed one canvas panel to the ground and picked up another, never chasing the light in one piece, but letting every change have its own space to speak. And again, he wasn’t slapping on the paint at 90 miles an hour; he was brief and deliberate, making exact notes that would bring a flood of memories back in the studio. His experience in the field was respectful and joyous, and that was conveyed in both the sketches and in the studio painting he did from them.

Here are some of the field studies done by Ray, and the studio painting that sprang from them:

Notice how pieces of the studies found their way into the final painting, which truly captured the spirit of the experience, even though that single scene only existed in his mind’s eye.

Having been a runner, I know that there are some people who are good long-distance marathon runners, and others who are good short-distance sprinters; there are very few people who are good at both. There are master artists who enjoy the quiet, drawn-out pace of a marathon painting, working weeks or months (or years!) on a single piece, but who could not do a one-hour demo in front of an audience to save their own life. Then there are master artists who absolutely love the adrenaline-fueled fast pace of the quick-draw events and are astonishing in their ability to nail a sketch in one or two hours, but who could not spend any more time than that without going stir-crazy, and would never re-enter a painting that’s been “finished.” But! Sprinters do run long-distances when they are in training, and distance runners do train by running sprints for the same reason: it makes them better at what they’re good at.

So there are sprinter-painters who start out with a bang and run full-tilt to the tape, and there are marathon-painters, who have a relaxed stride and who pace themselves to endure a long run. But here’s the thing: painting is not a performance art. Jill’s right: the thing that will outlast us is the body of work we leave here. Focusing on speed, even if I secretly still want to paint fast, is focusing on the wrong thing. Use speed-painting as an exercise, not as a standard of excellence. Paint a lot! Remember, a million miles of canvas is one of the things it takes to make a great painter. And the more a person paints, the better a person learns to say more with less. It will happen at some point that it will take less time to do that well.

Ray Roberts and Jill Carver are able to produce masterpieces in the studio that are gleaned from their work in the field. They are also able to produce truly inspired pieces in the field because they are out there working in all weather, day in and day out: they are good because they train and hone their gift.

So now that the Year of Painting Fast is half over, I’m reassessing. Sometimes a person has to readjust their goals in order to be true to their purpose. My real purpose is to be the best artist I can be, and maybe I, personally, can’t do that by painting fast. We who call ourselves artists have chosen to run a road that is not easy, but we love it and that’s why we’re here. Applaud the sprinters, cheer the marathon runners, and enjoy your own journey. Press in happily and hard to the thing that makes your heart skip and sing when you paint. There are a lot of things going on out there but we really don’t have to do them all; we’re not failures if we don’t do them all. We need to just do our best thing in the very best way we can. Getting to do what you love is such a rare thing. We shouldn’t ruin it by wishing we could do something else. I think the thing I was starting to lose in my quest for quickness was the experience of just enjoying spending that time doing what I Iove to do! That old adage, “haste makes waste,” is an old adage for a good reason: it’s true! Haste could waste the thing that made you start on this road to begin with: the joy of painting.

So I’m adjusting my sights for the second half of this year: the point is the product, not the pace; this is not a race! I’m going to write a card to stick to my Soltek: “Haste Makes Waste~ Embrace Your Pace.” Even if I still feel the need for speed!

7×11

“Painted Between 2 & 3:45 Whilst Competing Against Kim Carlton”