Two years ago I had my work critiqued through Oil Painters of America. Todd Williams was the Signature Member who looked at images of ten of my current paintings. He gave me some very helpful insight into my work and useful suggestions. One particular idea he proposed to me was very surprising and has resulted in unexpected changes in the direction of my work.

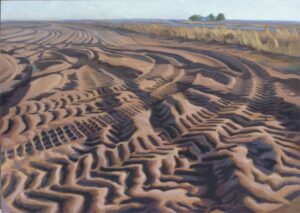

This is the painting he was discussing. He said something like this: “I notice that you have stylized the clay in the riverbed at the foreground, but you have not stylized the bluffs or sky in the same way. So I am suggesting that you consider the idea of whether you would wish to have stylistic unity in your painting.”

I had never heard anyone talk about stylistic unity, nor had I considered such an idea when making this painting. I knew that somewhere in this suggestion was a powerful catalyst for change in my work. I could not accept the idea of stylizing this entire image in the same way that the clay was treated. So I did not really know where to go with it. But what became clear to me was that the patterned clay was a big part of the reason that I keep returning to this part of the Brazos River for imagery. So in some of my next paintings I gave pattern a stronger voice in my work.

Then I did get back to painting the Brazos again, and here is the evidence of the power of this idea.

So here I am back at the Brazos River. This painting has more stylistic unity than Miller’s Bend. I am happy with the painting. The water is mostly realistic and I have had more fun with the patterns on the right. The concept of stylistic unity is still driving change in my work and is a challenge I am enjoying wrestling with.

OPA Critiques

Are you interested in having your work critiqued by OPA Signature and Master Signature members? OPA offers this service for a minimal $25 fee that goes to support the preservation of representational art, and you receive expert advice enabling you to become the best painter you can become. Click here to learn more about OPA Critiques.