When we moved to Silicon Valley for my husband’s medical residency in 2014, our family of five could barely afford our two bedroom, 900 sq ft apartment. I was raising three kids five and under in an unfamiliar city while my husband practically lived at the hospital.

Just two years before I had a dedicated studio outside our home for a time, and with the help of regular babysitting trades, I was producing new paintings, and had managed to put together a solo show. But now the lack of a dedicated workspace, combined with the challenge of rebuilding a support network, left me artistically uninspired–it was the lowest point I can recall.

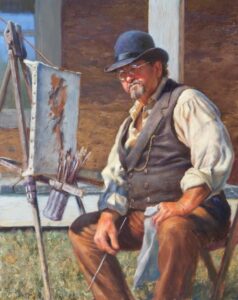

Oil on board

After surviving that brutal intern year, my husband threw out a crazy idea. “Why don’t we sell our bed and convert this bedroom into your art studio? We can sleep on the pull-out bed in the living room!” He was actually serious and in less than a week, our bed was listed on Craigslist and I began organizing a new studio space that would function as my artistic sanctuary for many years.

That was the beginning of our creative thinking about how we could create a functional artistic workspace in a small environment. Over the years I’ve invested in features to hone and refine my space for greater functionality and productivity. I love this quote by Paul J. Meyer: “Productivity is never an accident. It is always the result of a commitment to excellence, intelligent planning, and focused effort.” I now have everything I need in a compact 5’x6’ corner of our living room. I have seen that a clean, functional studio matters far more than the size of it. When I am in a space that is free of clutter, I can just sit down and paint when inspiration hits instead of spending 30 minutes to an hour getting things in order (speaking from past experience.)

I am not an organized person by nature and we do not live in a constant state of order, despite my minimalist aspirations. Fortunately, we are getting a little more organized each year. It is a process that takes concerted effort and directly impacts productivity in every area of my life. Below are some of the key features that I value in my current, compact workspace.

Key Feature #1- Oversized Carpet Chair Mat

Aside from the kitchen and bathroom, every room in our apartment is carpeted. After carefully measuring the floor space I had available for my corner studio, I searched for a durable, wipeable carpet protector and found it on Uline: heavy duty carpet chair mats up to 6’x8’. I ordered a 5’x6’– a perfect fit for my art corner (and another one to go under our dining table).

Key Feature #2- Mounted Fold Out Desk with Storage This particular desk is not currently available on Amazon, but there are others with a similar design and function. I leave the desk extended daily, but it can be folded up when not in use. We mounted a wooden board horizontally along the wall for added support before mounting the desk. If you need help with mounting, many cities have “task rabbit” or similar services that allow you to hire a handy person for building and installation projects. I am fortunate to have a very handy father-in-law who helps bring my studio visions to life.

Key Feature #3- Mounted Laptop Arm

I purchased this mountable arm so that my computer could “float” beside my easel at a comfortable angle. I later discovered that it also functions as a shelf for still-life studies with two white panels and a little tape. I have also used cardboard boxes, black binders, and other random configurations for my still life paintings. It need not be fancy.

Key Feature #4- Floating Palette clamped to easel with Manfrotto Camera ArmI learned about this palette set-up when studying with Elizabeth Zanzinger. By attaching her wooden palette to the camera arm she could clamp it to her easel and then adjust it to a comfortable height without needing to hold it. I’m a big fan of this system. I use a 16×20 New Wave glass palette with a wooden block glued to the back, that is attached to the Manfrotto arm. I love that I can easily adjust it for sitting or standing which has been much easier on my back.

Key Feature #5- Techne Artist Light with Clamp

If you are unable to install lights on your ceiling, this daylight Techne lamp is a decent space saving option. I highly recommend the article by Dave Santillanes OPA, “Geeking out on Studio Lights” for a more in depth look at lighting.

Key Feature #6- Westcott Softbox Light

I snagged this for a great price when an atelier closed, but linked to the Westcott site if you want to explore softbox options. Not only does it provide beautiful soft light in my studio, but it is wonderful for lighting subjects for portrait paintings.

Key Feature #7- H-Frame Studio Easel

This $99 easel sits away from the wall at the same distance as my mounted computer arm so for my current set-up, this works beautifully. But someday I would love to build a wall easel similar to what Julianna O’Hara, a fellow Californian, recently shared on the OPA blog. Read more about her frame storage and space saving tips here!

What I have shared above are some of the features that are working well for me in my current space. What I have not highlighted are the stacks of panels and paintings behind our couch, and the Ikea bookcase and storage containers filled with art supplies on our balcony. Those storage systems are not ideal and I will keep working to find better solutions!

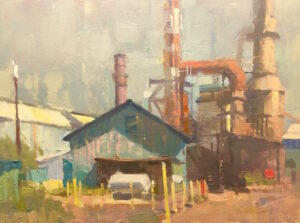

Oil on wood panelOut of the Box Finalist, PSA Competition 2019

I transitioned to this living room studio in February, the month before the first shelter-in-place went into effect. I now have three kids distance learning at home (and a seven month old!) Unlike that intern year, when I abandoned art for a time, this year I have the space and determination to paint. I am getting better at picking up right where I left off. Having my studio in the living room has been a blessing because I can be painting while also listening to my 1st grader’s class, and I can help as needed.

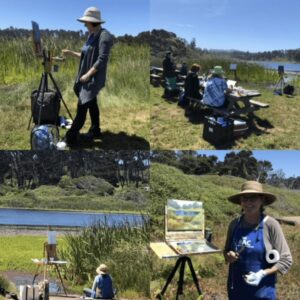

2020 has been about embracing change and adapting routines to meet the moment. Before Covid, I loved to do portrait work. Right now I find portraits to be too stressful so I have embraced still-life painting. I find it particularly meaningful to paint objects that are significant to this uniquely challenging time. The panel below was created over ten days as part of the strada easel challenge last month. I painted one object from life each day and it is filled with symbolism about my family members and our experiences during Covid and the wildfires in CA.

Oil on board

Life is constantly pulling us in a million directions and it would be easy, and perhaps justified, to press pause on our creative pursuits right now. But these are days to be remembered and recorded! If you are not inspired by your studio space right now, think about what small and/or drastic (sell your bed?) adjustments might make it a little more accessible or functional. Purge the clutter. Keep the essentials. Invest in some quality equipment when possible. And get to work! Capture these uniquely beautiful and challenging days for historians to look back on. You won’t regret it.

Oil on board