1. Paint your favorite drink – whether it’s a cup of tea, a pina colada, a steaming latte with lots of foam, or an ice cold beer – paint it in such a way that would show the viewer why it’s your favorite and how much you love it.

2. Go through the newspaper and find a photo – the first one that catches your eye – and paint your version of it – it could be abstract, realistic, finger-painted, or painted any way that might get your creative juices flowing for the next project.

4. Paint yourself as a person with the occupation you wanted as a child – did you want to be a fireman, a hairdresser, a bungee jumper, a police officer, a dancer? Give yourself a day as the person of your childhood dreams.

5. Do you love spaghetti? Eggs benedict? Chocolate Mousse? Strawberries? Your secret recipe? Paint it so everyone can taste it with you.

6. Repaint the first thing you ever painted. Just knowing that you now have a greater technical knowledge will help you paint that image with confidence.

7. Paint your worst habit – do you smoke, drink, eat too much chocolate? Paint in a way that will show how bad this habit is. Perhaps your painting, over time, will actually even help you quit your habit – if you even want to.

8. Paint about conformity – peas in a pod, ducks in a row, bananas in a bunch, etc. Make sure that part of your group doesn’t conform – for instance, leave one of the peas out of the pod.

9. Paint yours or your child’s favorite toy. Show some of the worn areas that clearly display how much it has been loved.

10. If you’re really hoping for some particular thing in life – paint it – maybe a cottage at the lake? A diamond ring? A new tool box? A particular make and model of vehicle? A child? Live your dreams through your painting.

Remember that at one time you only dreamed you could paint – now you truly can paint your dreams. Just make those first strokes that will put you back on your way – you can do it – you just need a little motivation. Hopefully you’ll find it here.

© Copyright · Susan Abma

Oil Painting

The Spirit Forges Ahead While the Brain Has To Figure It Out

1.) An answer for countless viewers who have remarked that I certainly painted a lot of different subjects. Now I had a way to tie many of them together.

2.) A better understanding of my artistic hard-wiring, which

a.) I can use on occasion to find what I want to paint faster and more easily

b.) In a purely narcissistic way—a fascinating (to me) fact about myself, of which, after all these decades I had been unaware.

Every piece I do does not feature white on a color field, but now when it happens, I smile to myself and recognize it as another chapter in my love affair with this combination.

If you feel there may be a hidden theme in your work, or some unrecognized essence, or you wonder how all your painting threads connect, I have a suggestion: block out some time for a lunch with a savvy artist friend and leisurely peruse each other’s portfolios. A fresh eye and a frank discussion may uncover a powerful current flowing just under the surface of your paintings.

What is FINE art?

The question that Keith raises, though, “What is Fine Art, Anyway?” is an important question for all artists to answer, I believe, because all artists who are working seriously—and seriously working—very much want to produce art that is truly “fine.” The dictionary defines “Fine Art” as that which is “produced for beauty rather than utility.” Wow, if we take that definition as gospel, that definitely undersells some of the most magnificent illustrations from the course of human history that have been created for books, churches, posters, hymnals, and advertisements. Just to mention a few, consider those “fine” illustrations from the body of work of such greats as Michelangelo, Rembrandt, Gustave Doré, and Rick Griffin (The Bible ) N.C. Wyeth ( Last of the Mohicans, Treasure Island), Howard Pyle (Robin Hood, King Arthur), Rockwell Kent (Moby Dick), Norman Rockwell (“The Four Freedoms,” “The Problem We All Live With”). Even my favorite artists, who probably created the first profession known to man, the cave artists (Lascaux, Altamira, the Magdalenians) might have been creating their art for utility—hunting and animal worship—or not. Perhaps it was the beauty of the forms themselves that captured their imagination, which in turn inspired them to capture that beauty in charcoal.

From the enduring quality of these artworks, it would appear that all those artists mentioned above—whose works were “illustrations” for definite purposes of dissemination—were intent on creating beauty within and emanating from those artworks, which then became “useful” (having a broad impact and appeal) as much as they were truly “beautiful.” How could those artists have captured the beauty of human form, its costume, the elegant turn of a whale’s fin, the power of a bison’s charge, unless they, too, had—as is very evident in Keith Bond’s work—“a reverence for the world in which we live”—and a spirit of both “exploration and veneration.” In my own work, I am also hoping that that same spirit of reverence for creation and its Creator is both alive and evident.

Fine artists learn the foundational skills of effective design, composition, color choice and more because they know that those artistic choices, when effectively employed, will create symbolism, evoke emotion, and convey meaning. It is the constant honing of their craft that will produce “fine” works of art that will inspire and impact an audience, whether the channel for that art is a painting, a book, a sculpture, or an advertisement. “Fine” art is simply that which is finely expressed and executed.

Thanks, Keith, for your post. It helped me to answer some of my own questions about what I am doing , and further clarify in my own mind why the arts and dedicated artists—“fine,” illustrators, or otherwise—are all invaluable to our culture, and to our civilization.

Keep It Simple! Using a Limited Palette

When I first started painting, I’d walk into art supply stores and spend hours looking at all the different pigments and brands of oil paints available, and drool over all those luscious colors: aureolin yellow, cinnabar green, quinocradone rose (just the names alone made me buy them). I’d load up my basket with dozens of tubes of paint and head home thinking that at last I had found the color that would make me a better painter. Age and experience are wonderful teachers, and I finally came to the conclusion that no special pigment would be the key to my success. In fact, the more choices I had on my palette, the gaudier and less-realistic my paintings looked.

In 2003, I had the good fortune to study with Scott Christensen, who at the time was using a very limited palette that he had his students use in his workshops. At first, I was baffled: how could I get a true yellow ochre using only 3 primaries and a couple of grays? How could I get a wide variety of greens when there were no green tube pigments on my palette? But after sticking with this limited palette for a while and experimenting with these colors, I came to see that I could mix just about every color in nature using only 6 tubes of paint. Using this palette also helped me to see and understand color temperature better by simplifying my choices: if the color needed to be warmer, I added yellow; for cooler, I added blue. And I found that the colors I was mixing were so much closer to the reality I was seeing than when I used a broader palette. When there are 20 choices on the palette, I find it’s much easier to just say “oh, that’s close enough” and dip into a color straight out of the tube , but when I have to mix my colors from the primaries, I get a more accurate representation of my subject matter. Of course, there are certain local colors that I can’t duplicate exactly with this palette, especially if I’m painting man-made objects. But I can always get the correct value and the correct temperature, and when those are right, the color reads correctly.

For example, the color of the water at Lake Tahoe is an incredibly intense blue-green. I may not be able to get that exact local color, but I can mix the right temperature and value, then surround that color with more muted grays and the color of the water will feel more intense and believable.

Over time, I experimented with adding and subtracting pigments from my palette and settled on the selection of paints that I’ve been using since about 2005. This is the palette that I use for all of my paintings, both plein air and in the studio:

Titanium White (any brand)

Cadmium Yellow Lemon (Utrecht)

Permanent Red Medium (Rembrandt)

Ultramarine Blue (any brand)

Naples Yellow Deep (Rembrandt)

Cold Gray (Rembrandt)

(Please note that the brands of the paints are very important as colors vary widely between manufacturers)

Although I use a limited palette for my paintings, I always start out by mixing puddles of several colors before I start the actual painting. Doing this accomplishes two things: it helps me to slow down and analyze the color before I dive headlong into painting, and it allows me to have an expanded choice of colors when I begin to paint. I always mix the secondary colors (orange, green, and violet) regardless of what I’m painting, and the rest of the puddles of color are close approximations to what I’m seeing in the subject matter. Pre-mixing takes some time at the beginning of the painting, but it really saves time once I start to paint: I already have so many colors figured out and can concentrate on the subtle shifts in temperature and value that I’m seeing. Also, I don’t break the rhythm of painting to drop my brush, get out my palette knife and mix new color.

Here’s a shot of my palette before I start a painting:

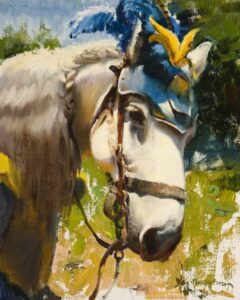

And here’s the finished painting from that palette:

There are certainly countless artists out there who use extensive palettes and get beautiful results, and my selection of pigments is just one way to approach painting. But if you have never used a limited palette, give this a try- you might be surprised with the results and be able to bypass all those rows of paint next time you’re in the art store.

Paint From Life or Photos?

There are a host of good reasons to use photos:

- They’re convenient

- The light doesn’t change

- You can blow up small details

- You can be comfortable

- There are no bugs, wind, interrupting strangers etc.

- The model doesn’t move or get tired

There’s only one really good reason to work from life – it will make us much better artists.

Over time, we representational artists become skilled at rendering what we see. The problem is that even high-quality digital photos lie to us. Think of the four elements of a realistic painting: shapes (drawing or proportion), values, color temperature relationships, and edges. Three of the four are always wrong in a photo… and sometimes it’s all four.

The two or three darkest values turn into black and the lightest values become white (photographers call it “blowing out” the lights). The color temperature relationships are limited by the dyes used to make the prints or the phosphors in our computer screens. Also, the camera sees edges as equally sharp (not at all like the human eye which focuses on a sharp area in the center of our visual field surrounded by fuzzy shapes on the periphery).

When I critique portfolios at various art events I often see paintings where the shadows are black, the lights are white, all the edges are hard, and the light and the darks are the same temperature. I ask the artist, “you work mostly from photos, don’t you?” I often get the astonished reply, “how did you know?”

The pros work primarily from life: For one, it’s much easier to develop good edge control. Also, our sensitivity to nuance of color and temperature improves exponentially. We just can’t see those nuances in photos… I know; I’ve tried! Working from life, we learn to see the elusive, sparkling color in half tones. Our shadows start to have a sense of light and air in them instead of being dense, opaque blobs.

So, if you’ve decided to go the extra mile, how do you break free of the photo? The still life is easy. Just set it up and start painting. Likewise, there’s little excuse for trying to paint a landscape from a photo. If you’re nervous about going out alone, find a painting buddy or group. There are Plein Air groups in most areas now. OPA sponsors paint outs all over the country. Seek, and ye shall find.

Once we start to see the benefits in our work, we want more. The little bit of extra effort to paint from life, pays off tenfold.

Happy painting!