To be a good figure painter you should know how to draw. My teacher Sergei Bongart would tell students to go home if they couldn’t draw and to not come back until they could. After they learned to draw they were allowed to paint.

To be a good figure painter you should know how to draw. My teacher Sergei Bongart would tell students to go home if they couldn’t draw and to not come back until they could. After they learned to draw they were allowed to paint.

I would like to present three possible ideas to help you learn to draw figures.

1.) Take a class

1.) Take a class

Drawing courses can be found in most communities and schools. Start at a level that helps you the most. Basics or an advanced class that studies anatomy. Figure drawing books are wonderful. Some of my favorites are by John H. Vanderpoel, George B Bridgman, Andrew Loomis and “How to Draw Comics the Marvel Way” by Stan Lee and John Buscema.

2.) Go to figure drawing sessions that offer short to long timed poses.

2.) Go to figure drawing sessions that offer short to long timed poses.

Two, five, ten, and 20 minute poses are very good for learning different parts of drawing. It took me a long time to fall in love with 2 minute gesture poses and I didn’t understand their value. By learning the value of quick gestures you can watch people in motion and capture their extreme poses. A long pose can help you develop your own style of drawing and give you time to study the figure. Use different kinds of paper and try charcoal, conte, pencil and pens. See what thrills you and helps you grow.

3.) Carry a Sketchbook

3.) Carry a Sketchbook

Beginning your sketchbook you should use a pencil. This will let you erase and fix your drawing so your talent and style can grow. Draw figures holding still. Airports, restaurants buses or anywhere figures are not really moving. Try to never let people know you are sketching them and develop tricky ways to observe. After you feel comfortable with the pencil try pens. A fun way is to use insoluble pens for the first part of your drawing and then add soluble color pens and a water brush pen to add interest. The most fun challenge for me is drawing people in motion like cooks at a restaurant, people waiting for the bus, or workers outside using their muscles with unusual poses.

Good luck and have fun. If your painting has a bad drawing it is doomed from the start so learn to draw.

Education

My Experience With A 100 Day Challenge

by Kelli Folsom

At the time I was exhausted, feeling stagnate getting burned out. Part of my exhaustion was due to overworking, teaching too much and primarily doing some teaching that was not a good fit for me at a local University for two semesters which was leaving me with strained studio time. So as I was doing my usual digging on the internet for new ideas, I wound up stumbling upon someone’s blog…. don’t remember whose now, you know how that goes. She gave a long list of resources some of which I had read and just weren’t for me and at the end, she mentioned this program called the 100 Day Challenge. I went and checked out the site and listened to some interviews with the creator on YouTube. I felt this instinct saying, “you need to try this.”

The Challenge started before tax time and before my 2nd semester of teaching was over. “Not exactly the right time since I’m totally frazzled,” I thought. Excuses, excuses…here they came. The second excuse: it costs $200. A third excuse: this is just motivational hype…. and more and more fear, panic and what will people think of me bull hockey. So, I signed up. I thought, what’s the worst that can happen? I lose $200. What’s the best that can happen? I learn some powerful lessons that actually change the course of things. BINGO. SIGN ME UP.

I signed up and kept it secret for quite a while afraid of judgments against it. Now that it is over I can happily report that it was an incredible experience – not easy, but incredible. Therefore, I STRONGLY recommend the program to anyone who wants to see some changes in their life – in any area. This is not just for artists or entrepreneurs; it’s for everyone. It’s not just to make money or lose weight; it can be for developing mindfulness or spending more time with your family or any area in which you would like to see dramatic growth. The program is designed to walk you through any goal and keep you motivated while working on it. You are the one that makes it happen though, by taking action and following through. So now I will share what my particular goal and experience was.

Disclosure: If you have weird beliefs about making money or are too much of an idealist and think that you should be a starving artist, READ NO FURTHER.

My goal happened to be a painting sales goal. I wanted the fulfillment of selling more of my work. I mean, after all, that’s part of why I’m making it right? The program encouraged you to set a big goal, to be clear on what you wanted. I already knew what my ultimate goal was for a yearly salary, but it always seemed so far off in the future, and I always thought, “Hey, what control do I have over whether or not people want to buy my paintings?” and “I have my work in galleries across the country, and I’m doing everything I know how to do otherwise to make an income.” Other thoughts included, “Geez, I hate marketing stuff. I don’t want to be a sleaze-ball salesman. It should be about the art. People will judge me for being superficial and caring about money.” (Insert dramatic eye roll) The truth was that I knew there had to be some other ideas or options and I already knew I was putting off a lot of things that would improve my circumstances. Although I was at the point of burn-out, I felt there was no better time than this when I’m sick of my current results and needing to re-focus.

So I set a big goal. Since the challenge was 100 days – roughly three months, my goal was 1/4 of what my eventual hopeful income will be … which just happened to be more painting sales income than I made all of last year! I thought wow, this will be darn near impossible. But I started the program with such excitement anyway, not with doubts, determined to give it everything I had. The daily videos from the 100 Day Challenge kept me focused on how to reach my goal; on days that I was sinking back into comfort zone or wanting to give up, the program kept the flame lit until I could see some more results. Halfway through the 100 days I had made more than 60% of my goal. I was so elated! Then the plateau came and all the doubts that came with it. The next 2 weeks (I know, long time right?) I saw very few results ….and started to think this was all I was going to be able to do. I became tired of trying, so there were a few days that I put out very little effort and felt bummed. I realized I didn’t want to end like that; I would rather not reach the goal, doing everything I could, than not reach it and wonder if I had really given it my best shot.

By the end, I am happy to report that I reached 95% of my goal! The goal was not simply about the money; it was about doing what I needed to do instead of blaming others and feeling powerless for what income wasn’t coming in. I took back responsibility and in turn felt more powerful and in control (not in control of the outcome mind you, but of my own actions and mind).

Here are the most practical applications I learned during the challenge:

1. IDENTIFY GOALS.

Understand WHY you want to achieve them. What will that success look and feel like?

2. BRAINSTORM.

Brainstorm ways that you can reach these goals. Just take a piece of paper and start righting down ANY idea that comes to mind…don’t judge it or say that’s a stupid idea. You probably already know lots of things you can do to help reach your goal, but if needed, then do some research. But be careful, as research can often become a form of procrastination.

3. PLAN YOUR ATTACK.

Set quarterly, monthly, daily, weekly, even hourly ways to reach your goal and keep track of which goals you meet. The biggest thing that helped me once I had a list of brainstorm ideas and actions was to plan out my day in 30 MINUTE SEGMENTS. Yep, 30 minutes. This level of attention was a life changer for me.

4. PRIORITIZE.

Sometimes, I have so many little things do that I’ll do those all day and have no energy left for the very important stuff. I mean, I’m an artist, not a housekeeper, people. What is going to move you closest to your goal the fastest? Take action on these first! You can’t get around some daily to-do’s… like food…we do need that to survive. Do them last, do them first, I don’t care…just do them fast and only the ones that HAVE to be done. Are there things you can hire out? Automate? Or not do at all?

5. FOLLOW THROUGH.

These were things I had been putting off because I just dreaded doing them, like computer stuff or spending money on advertising. OUCH. Now, I realize just how little time they actually took once I took action and how painless it was. BIG RESULTS on both of these, by the way. Also, there is no bigger self-esteem booster (in my opinion) than doing things that you have been procrastinating for two years. Yep, that’s right. You heard me. Two years. (Sigh)

6. RECOGNIZE YOUR HUMAN-NESS.

You’re gonna have days that you want to give up and quit. It’s okay. Go back to your Why’s on your goals. Think about how you’re gonna feel having reached them and take a day off! The program actually reminds you constantly of how important self-care is, that you are well rested, well fed, spending time in nature and with loved ones. You actually perform better and new ideas come to you when you do this. But when you rest, rest. Don’t be anxious that you don’t have your nose to the grindstone.

7. DO SCARY AND NEW THINGS.

Execute the ideas that scare you the most and the ideas that you’ve never tried. Be open to new ways of reaching your goal. We tend to follow what’s modeled for us. I mean, you only know what you know how to do, right? Wrong. Open up to other ways, look for other options and question previous beliefs. One thing that happened to me was that I started getting requests for commissions just out of nowhere. I’ve rarely done commissions before, and I didn’t care for it when I did, but I was open and said YES. The commissions brought in 30% of my sales goal, I had no conflict with the clients, and I enjoyed doing the paintings.

There are people out there who will never need something like this. They’re just cool how they are. I wish I could be that way, but darn it, Jim, I need some help sometimes. I don’t get anything from the 100 Day Challenge for sharing this information with you, but I was so happy with my experience I wanted to share it in hopes that it might help someone else, however needed.

Check it out here: www.100daychallenge.com

Nancy Boren interview

I don’t remember when I first met Nancy Boren, but it was many years ago. I actually met her parents, Jim and Mary Ellen Boren, before I met her. It was in 1984 that I met them after being invited to go to Spain and Portugal for two weeks of painting with a group of amazing artists that annually participated in the Western Heritage Sale. They were on that trip.

Jim Boren was the first art director of the National Cowboy Hall of Fame in Oklahoma City. He provided expertise and leadership in assembling the Hall’s fine art collection and exhibits. In 1968, he became a member of the Cowboy Artists of America. His favorite medium was watercolor. So, Nancy grew up around art and the western themes painted by her father. Although she has found her own voice, the influence from her childhood remains. At this year’s Oil Painters of America National Show, Boren was a huge winner, taking the Bronze Medal and Artist’s Choice awards for her painting “Thunder on the Brazos.”

Her greatest passion as an artist is figure painting. Although she has many interests and her painting subjects do vary, she’s most attracted to sunlight and often depicts her subjects in direct light. Three artists she would like to spend a day with are: Nicholai Fechin in Taos, Emily Carr in a British Columbia native coastal village, and Childe Hassam on Appledore Island.

When I asked her how she typically works with clients that commission a painting, I really enjoyed her answer. In a humorous way, I am contemplating just which dogs she might be speaking of. “I almost never do commissions. My heart just isn’t in it. I used to do pet portraits, and when I did those, I would take lots of photos in different lighting situations, then do a 5 x 7 oil sketch. After approval, I did the larger painting. Occasionally the clients also bought the sketch to take to their office or lake house. Much patience and time was required; however, I really did meet some great dogs.”

I know you’ll enjoy this interview with Nancy Boren; with pleasure I bring it to you.

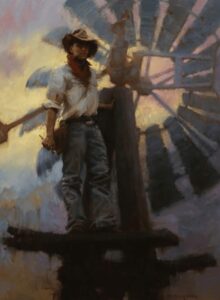

30″ x 24″ – Oil

(Bronze Medal, Artist’s Choice Award – 2016 Oil Painters of America National)

What is your definition of art?

Art is a creation that must contain beauty. Not necessarily beauty in the subject, but in the presentation and execution of the idea. John P. Weiss says that people long for beauty and creative expression. They want to be moved, inspired and shown the hopefulness of art and I agree with that.

“I have had the great good fortune to be born in a place and a time where the luxury of being an artist is a possibility. I am one because I have the opportunity to be what I was born to be.”

Your Dad was a well-known, very accomplished artist; what influence did he have on you becoming an artist and doing the type of work you’re doing today?

He was a huge influence. I grew up seeing him happy, productive and successful. Like him, I also enjoy doing art in a traditional vein and have been familiar with wide open spaces and western subjects all my life. Of course I also paint more exotic figures from time to time.

30″ x 32″ – Oil

When I started doing the pieces for my first show with my dad in about 1978 for some reason (safety?) I did ink and watercolor wildflowers similar to botanicals. Next I started doing watercolors of old interesting buildings, the Taos pueblo, and landscapes. I had used wc growing up and my dad did watercolors as well as oils, so it seemed easy and familiar. In college at Abilene Christian we never did an oil, only acrylics in the painting classes and I found I didn’t like acrylics at all. I later started painting in oils, I don’t even remember how that came about, I just did it. I didn’t want to do the same subjects as my father, but I was in the same galleries so it was a bit perplexing as to how to establish my own identity. I just went at it one painting at a time, but I liked cowgirls — I lived in Texas for goodness’ sake — and so I finally started doing them because that was a western subject my dad never did. Costumes and hats appeal to me in figurative work so it was a perfect fit.

You seem to be equally attracted to landscape and figurative subjects; what is the attraction to each?

I love figure painting the most, but I love landscapes also. One is a nice change from the other. I need variety.

Maine (Plein Air)

9″ x 12″ – Oil

(Finalist, Bold Brush Competition –

Dec. 2015)

I do paint from life and attend figure painting sessions but most of the paintings I put in shows are done based on photographs. Some would just be impossible for me to do otherwise — especially people on windmills or figures jumping.

34″ x 38″ – Oil

(Gold medal for Signature Members of American Women Artists Show – 2016)

“I hope my work shows how intriguing I find the world.”

You have created several very impressive figurative paintings with windmills…very interesting and compelling compositions. How were these set up and accomplished?

I decided I wanted to do a windmill piece and so I googled windmills. I found a place a couple hours from me that has a whole group of them and the public is welcome. I take my models or have them meet me there. Then I stand on the ground and direct them, and take lots of photos.

Do you have a pretty clear concept in mind before beginning a painting; if so, how do you work out your concepts?

I usually do have a clear concept in mind. I do most of it in my head. I may cut up a photo I have printed out, or paint over part of the photo, or do some erasing in photo shop (but I am far from a tech guru so the simple way is how I approach it). I know people tout the great benefits of thumbnails, but every time I try them I get annoyed and disgusted because they don’t look anything like the finished product I want and so as a result I would rather work out things on the painting itself. I try to look on the bright side, because when I leave bits of the original color showing through and around the changes, the painting is actually more interesting than it would have been had everything been perfectly planned out at the start. At some point after you learn how to do things conventionally and correctly, you have to embrace your own quirkiness and go with it. For a few larger paintings, I have done small studies (8 x 10 up to 12 x 16).

12″ x 16″ – Oil

(Honorable Mention, Plein Air Southwest Salon – 2016)

20″ x 36″ – Oil

How do you come up with your ideas?

Two ways: I see something that would make a good painting, or more often, I set my mind to work on coming up with something. I think while I drive, and I look for things to spark ideas. I love this quote by Thomas Edison: “To be an inventor you need an imagination and a pile of junk.” My junk pile is composed of colors, shapes, outfits, people, weather, animals, stories, and props. I love treasure hunting on back roads, antique stores, on walks with my dog…everywhere. One fascinating object can give me a painting idea.

What is it that you primarily want to communicate through your work?

The immediate answer would be for each painting to convince a collector to take it home. But the larger answer would be sharing an honest delight in the world and the hope that my slice of life will resonate with someone else out there. And I hope that the blood, sweat, and tears that went into it are transformed into convincingly light, right strokes of paint.

“Artists of all kinds add the spice, the eye-opening moments, the richness to life.”

What’s the major thing you’re looking for when selecting a subject?

Many times I think in terms of silhouettes. An interesting silhouette like a windmill always grabs my attention.

Please explain your painting process. Does the process differ when working plein air versus studio?

I pretty much start the same way no matter what color scheme, size, or location. I draw with thinned oil paint (often a transparent color like olive green or a mix with transparent oxide brown) to get all the big shapes in place, sometimes on a toned canvas, sometimes not. Then I use more thinned paint to get the darks and colors suggested before beginning to paint with thicker pigment. Lots of times I start with the focal point, but sometimes I work around it. I would say it is the approximate trial and error system. I can’t completely finish one area with white canvas surrounding it before going on to finish another area; that just does not work for me.

36″ x 24″ – Oil

silver metal leaf

16″ x 20″ – Oil

How do you decide on a color scheme for each painting?

If I see something beautiful I may try to replicate the effect, so the subject informs the color choice. Sometimes I want to paint something red because I have just finished a painting with a lot of green and I am sick of green. When I am frustrated with color I go to a limited palette to give my brain a rest and to enjoy the subtle surprises those color schemes hold.

What colors are typically found on your palette? Why these colors?

Zinc-titanium white mix, cad yellow light or medium, cad yellow dark, orange, yellow ochre, cad red light, permanent alizarin, sometimes cad red deep, burnt sienna, transparent oxide brown, cobalt or ultramarine blue, sometimes manganese blue, sometimes olive green, ivory black. Sometimes a few others also, but I don’t use everything on every painting. I use a Zorn palette on occasion. Through the years colors have come and gone.

What are the compositional guidelines you always adhere to when

designing a painting?

I doubt I always adhere to any guidelines. I do try to stick with odd numbers of things instead of even and I try to use repetition. I try to have only 3 or 4 big areas of value.

I have attached the original photo I used that I took with my cousin posing on a windmill as well as the 16 x 12 color study. The photograph shows that is was an ugly gray day with virtually no color in the sky or anywhere else. As we drove away, the sun snuck out from between the clouds for a moment and so the sky was reconstructed and enhanced from my quick glimpse of it.

The photo, used as reference for “Aloft in the Western Sky”, shows Boren’s cousin posing on a windmill. Next to it is her 16″ x 12″ color study. Boren says it was an ugly gray day with virtually no color in the sky or anywhere else. As we drove away, the sun came out from between the clouds for a moment, so the sky was reconstructed and enhanced from my quick glimpse of it.

How has your plein air work informed your studio creations?

Cameras are great for detail and lots of information, but plein air studies are great for feeling and color. I have done paintings using a combination of the two: plein air for the color and photos for the arrangement (especially of things blowing in the wind).

Do you have a marketing strategy for promoting your work?

Perseverance is always key. I try to do quality work, get in quality shows and galleries. I do have a web site, which I keep reasonably updated. I post on Facebook and Instagram, and I enter competitions, as well as belonging to several national groups. Good things have happened as a result of several of those areas. Honestly, I am more concerned about my next painting than about my next marketing effort.

Start today. Even if you can only work a short time each day, start. And use what is at hand, like the children. They will grow up so fast, time is of the essence. A tremendous amount can be accomplished in small spaces and in small blocks of time and there is nothing wrong with doing small pieces that can be finished quickly. Donna Howell-Sickles used to get up at 4:00 in the morning to have two uninterrupted hours in the studio before her daughter got up. I don’t know that I would have had that kind of dedication but I do believe in just doing it; figure it out as you go.

If you were stranded on an island, what three books would you want with you? How to Survive being Shipwrecked and Get Rescued, one of my scrapbooks of art I have clipped out of magazines, and Night Circus.

What’s a typical day look like?

Every day is different. I do love days when I don’t have to leave the house (where my studio is) except to take a walk. I often run errands in the morning because I am an afternoon person. My husband gets home from work at 7:00 so I can get a lot done after lunch.

Nancy, thank you for a great interview. Your plain spoken, down-to-earth responses will be greatly appreciated by the readers of this blog.

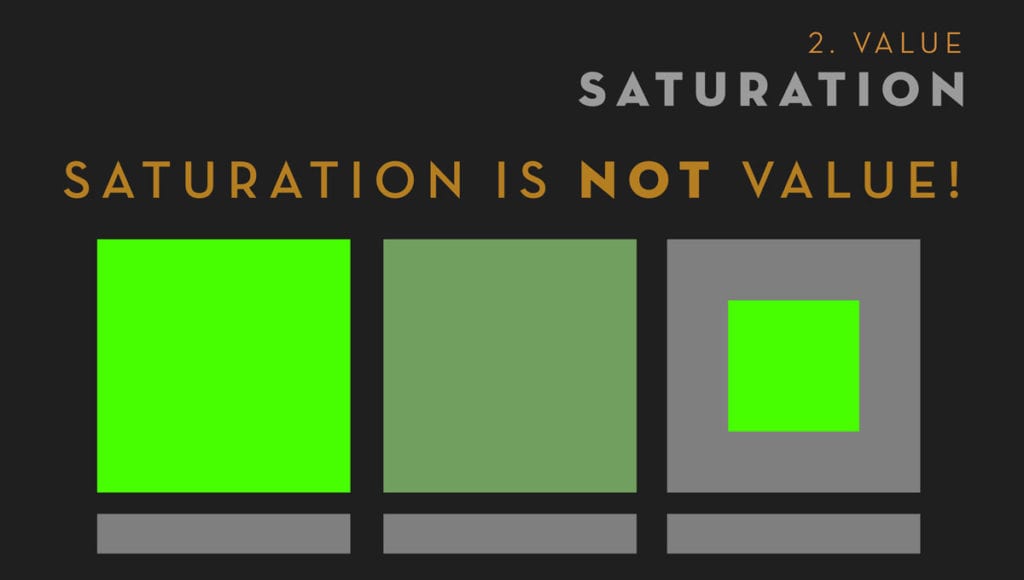

BACK TO BASICS: VALUE

In a spring post, I spoke about the importance of drawing in the hierarchy of a painting’s success. Value was the second item listed:

1. Drawing

2. VALUE

3. Color

4. Edges

In this post I’ll mention a few items regarding the importance of value as a foundational principle of strong work.

Drawing alone can’t fix a piece, the values have to be working. I fully acknowledge that we all know that correct values are important in painting, but the level to which I see even experienced painters (myself included) struggle with this convinces me of the need for constant awareness. As with so many things in life, it is the seemingly simplest things that are the most profound and the most challenging to master.

I break value down into three ideas:

1. SILHOUETTE:

Basically, it comes down to camouflage. Camouflage works because it scatters contrast and breaks up the silhouette of shapes. This makes sense intellectually, but even being aware of the effect, it takes a conscious effort to avoid it happening in artwork. Use this to your advantage and keep things clear in your focal point and more compressed value-wise in other areas.

2. THREE-VALUE STRUCTURE:

I can guarantee that nearly any painting I am moved by has a simplified value structure. Compressing and simplifying values to Dark, Medium, and Light will help communicate more clearly and feel more ‘real’. Again, it is seemingly straightforward, but it is surprisingly hard to do well. Thinking of these three distinctions in terms of ‘value families’ instead of only one value option may help.

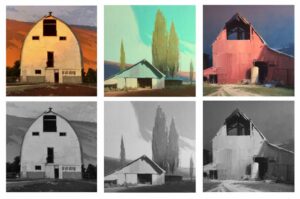

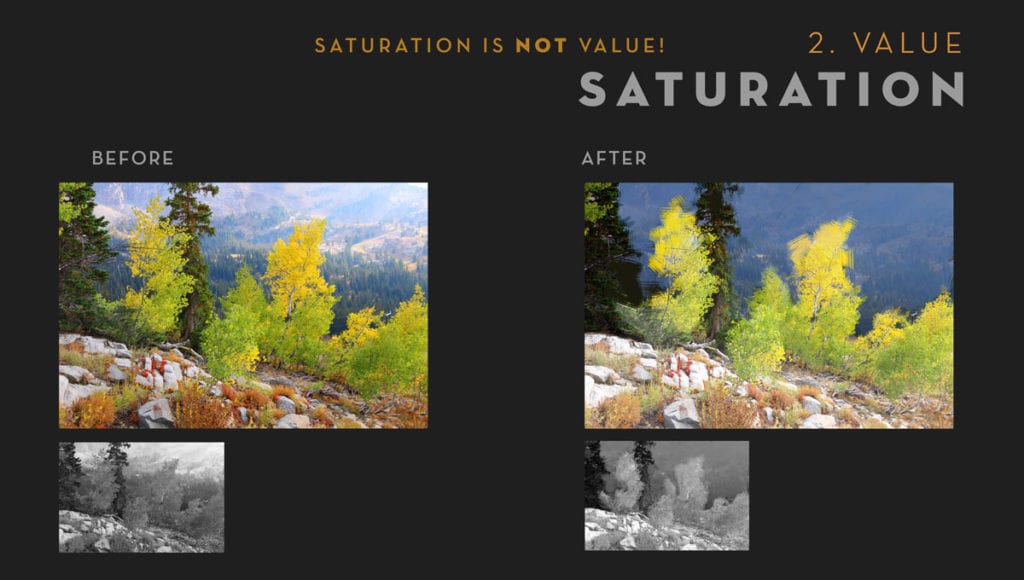

3. SATURATION:

Saturation isn’t value, but we sure act like it is sometimes. We get sucked in by the color, and we get stupid. I do this all the time (ok, some of the time).

In this final example I’ve shown how I adjusted a piece of photo reference by pushing the surrounding value a little darker so as to read light-on-dark, as it was already leaning in that direction.

Usually, if a color is vibrating your eyes, you’ve got a value problem because the value and saturation are getting too close. This obviously can be used to your advantage in areas that you want to shimmer (such as a sky or mountain) by alternating temperatures slightly while keeping values close. But when you see this shimmer happening all around your main shapes you should pay attention to the alarm bells going off in your head because the shapes aren’t going to read well. Usually getting some distance from your canvas (i.e., across the room), and squinting is a good way to see what’s really going on.

Finally, to quote the great art teacher Leon Parson: “If there is a problem with your painting, it comes down to one of five things (Imagine him holding up a hand and counting down on fingers): value, value, value, value, or value.”

Happy Painting!

Put Yourself Out There!

As artists, we are forced to open up and put our inner thoughts and emotions into our artwork, then out on display for the whole world to see. A lot of times we get negative feedback, such as “It is with regret that we inform you that your painting: ……… was not selected for inclusion in this year’s show. The participation and quality of work submitted was exceptional. The jurors had a very difficult job of selecting show paintings from the paintings entered. Unfortunately, your artwork was not selected for this exhibition, however, please join us for the opening of this year’s exhibition”, and it hurts.

I was just starting to paint and gather up the courage to enter shows, then I would receive something like the above. I was disappointed, but I was also more motivated to improve my skills, dig a bit deeper and become a better painter. I progressed a bit more in my artistic career by painting more regularly and getting constructive feedback from several close teachers. I came into a period of artistic bliss where I was starting to get into more events and accepted to more exhibitions. During this time I helped co-organize an exhibition called “Northern California Impressionism” at the Peninsula Museum of Art. It was an exhibition with nineteen nationally-known artists that was designed around the theme of “plein air to studio”. It was definitely a high for me to work with these noted artists, participate in this exhibit and bring our work to the Peninsula Museum of Art for the community. The exhibit was very well attended and several magazine articles were written about it. Life couldn’t be better.

As this show was closing I applied to 5-6 exhibitions and plein air events. The notifications about these shows would come in three to four months. As the time approached, I was very hopeful that I’d get into at least one of these shows. But as you probably guessed I did not get into any of the shows.

Before, the rejection did not hurt as much because I was not as hard on myself, I figured that it was because I did not have as much experience as the other artists or because there were obvious mistakes in my art. But this time, the rejection really hurt, especially because I was not sure what I was doing wrong in my work – especially after my recent successes! I confided in another artist who is farther along in their journey and success as an artist and they said “What this is telling you is that your work is missing something”. It was hard to hear, but I appreciated their honesty. I started to look closely at my work to see what was missing. This idea of this “something” missing from my paintings was starting to get to me. At this time, I was reading “Art & Fear” by David Bayles & Ted Orland and came across this quote,

“The lessons you are meant to learn are in your work. To see them, you need only look at the work clearly – without judgment, without fear, without wishes or hopes. Without emotional expectations. Ask your work what it needs, not what you need. Then set aside your fears and listen, the way a good parent listens to a child”

(Bayles, D., & Orland, T. (2001). Art & Fear. Image Continuum Press Edition).

So, I did.

The next time I went to the studio, I spent a lot of time analyzing my paintings and looking at work by other artists that I admired. I tried to push away my biases and put myself in the shoes of another artist or juror. I then asked myself what was wrong. What would I change? Why would I choose this painting for a show? Using this method of objectively judging my own work, I was starting to see what was missing.

About the same time, I got a call from a local art organization that saw my web site. They told me that they liked my work and asked me to do a demo. I said yes, but I was nervous. This would be my second demo ever, and my confidence was down from those recent rejections. I did not want to disappoint the people who had come to learn from me.

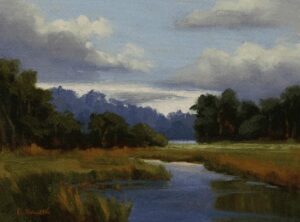

Having to do a demo for a group motivated me. I wanted to do a good demo so the group could learn some new skills and techniques. I decided to paint a marshland with water reflections. I spent several days at the marshes taking photos and painting small 6″x8″ studies. I drew several compositions and charcoal value studies of the designs. Then, I painted two 9″x12″ and used my 6″x8″ studies and drawings as references. A week later at my demo, I felt prepared and excited to talk to the group. My demo went very well and the group had lots of good questions for me. The group really liked my work and said it was peaceful and tranquil. They also commented that with all the tension in the world it was great to be transported to a peaceful place where they could come relax and focus on art.

The work that I did for this demo and the positive feedback I received put me back on track. I got my confidence back. I began to use this process of objective judgement to produce better paintings and my skill level started improving again.

Ellen Howard

Several months later I entered the two 9″x12″ paintings I did for the demo in some shows. Both 9″x12″, titled “Last Light” and “Reverence” were accepted into the Laguna Plein Air Painters exhibit titled: “California, The Golden State” and then on July 28th I received:

CONGRATULATIONS!

Your entry “Last Light” has been accepted into NOAPS 2017 Best of America Exhibition and will be hosted by The Castle Gallery Fine Art in Fort Wayne, Indiana.

The two 6″x8″ studies I did for this demo were chosen for exhibit by my gallery in Marblehead, MA.

Ellen Howard

9″ x 12″

Ellen Howard

9″ x 12″

From this experience, I’ve realized that a person’s development and artistic success does not go in a straight line. Rather it goes up and down, just like life. Progress in art is very personal.

“Look at your work and it tells you how it is when you hold back or when you embrace. When you are lazy, your artwork is lazy; when you hold back, it holds back; when you hesitate, it stands there staring, hands in its pocket. But when you commit, it comes on like blazes”. (Bayles, D., & Orland, T. (2001). Art & Fear. Image Continuum Press Edition.)

Since then, I’ve been in another positive growth period. I can see that I am more consistent with my work and I’m making the same mistakes less and less frequently. I don’t compare my work with others. I compete with myself and ask, how can I improve? How can I paint that scene better? Did I capture the light? Did I push the colors enough? It is a good place to be right now.

“Naïve passion, which promotes work done in ignorance of obstacles, becomes – with courage – informed passion, which promotes work done in full acceptance of those obstacles”.

(Bayles, D., & Orland, T. (2001). Art & Fear. Image Continuum Press Edition.

For me, I can’t think that I will progress if I play it safe. I need to take chances in my work and to say “yes” to opportunities that might make me feel a little uncomfortable at first, but will make me grow as a person and as an artist. It’s amazing to me that a little push in the right direction can bring unexpected and pleasant surprises. If you don’t take a shot, you’ll never hit the target – so you gotta take that shot!